It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

I used to, but not anymore. I was pretty enthusiastic about them 10 years ago after I met with one of the founders. I found their approach to investing and vibrant team pretty compelling and unique. However, performance started becoming mediocre around 2015 and their fees are high, then portfolio managers started leaving, and not to retire, but to other competitor firms. I can't list all the names, but i recall at least 10 relatively young portfolio managers leaving the firm in the past two years, which is meaningful given the size of Matthews. Something seems off with the team and overall company. Not something we haven't seen happen at other boutiques. Its tough to stay hungry and not slip into complacency and mediocrity. The recent departures, who again are all relatively young, tell me people are jumping ship and there are bigger issues at play than just poor performance.I taken that you don't invest with Matthews Asia funds or have high opinon of their outlook? Though I agree that Matthews Asia funds have not excel with the exiting of several experienced managers.

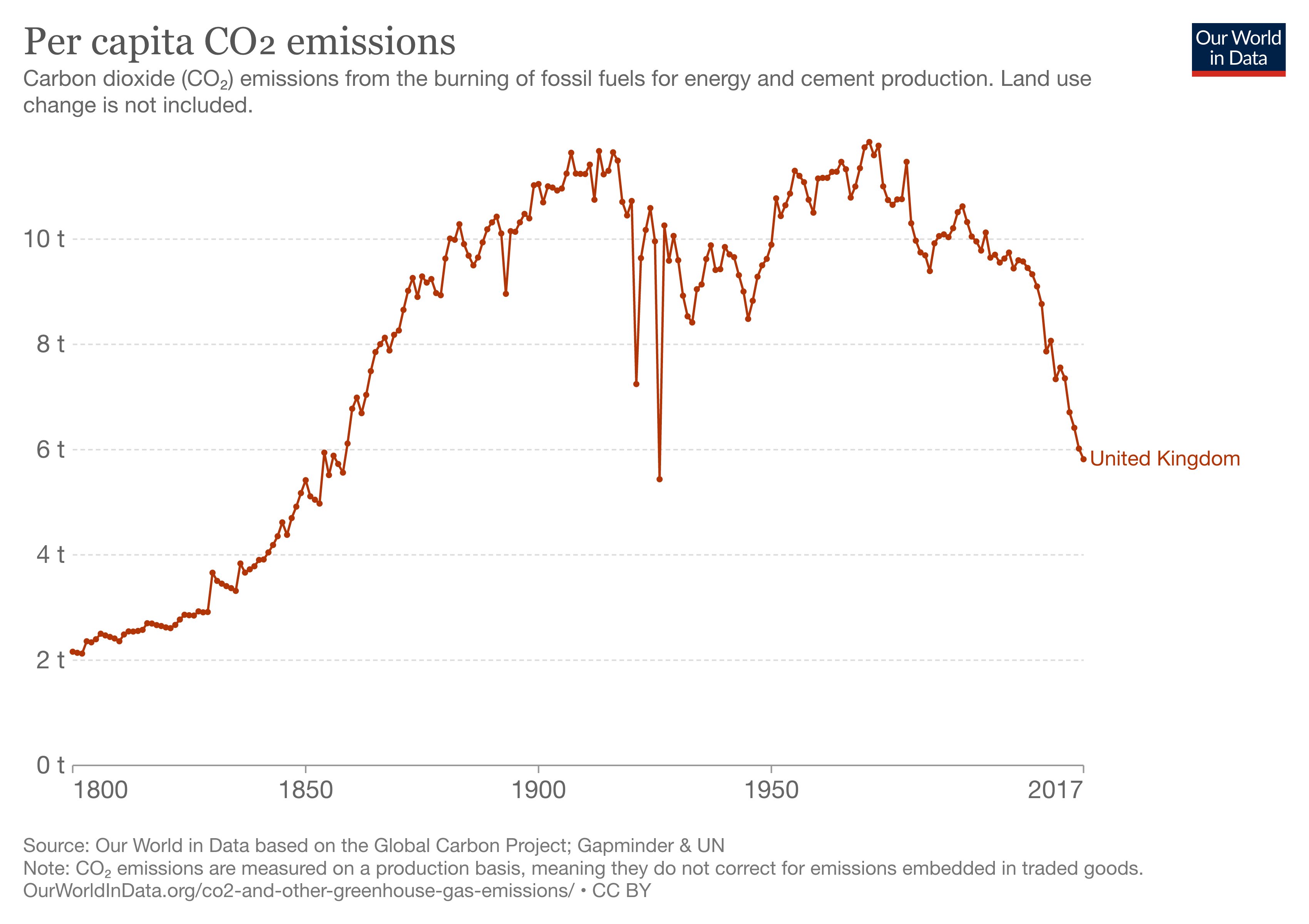

Yes. That is encouraging. The image doesn't show up on my computer....just the word "image". But going to the link I sleuthed when previewing this reply provides the image. Weird....this is cool --- the UK's 1850 levels

‘net-zero emissions’ target is one source for more details.The electricity sector is where the large majority of UK emissions cuts have occurred over the past decade, during which the country’s power supplies have been transformed.

Bury CarbonSkyrocketing carbon prices and a “code red” warning about the threat posed by climate change are giving fresh momentum to a technology that captures and removes greenhouse gas emissions so they can be buried.

Slow SlogThe gains are smaller, befitting a less hysterical year. When the S&P 500 Index has risen in 2021, the daily increase has been half what it was in 2020. But in terms of persistent, day-after-day gains, these seven months in the U.S. stock market have few historical precedents.

Over the last century, there has been just one other year when the benchmark set more high-water marks by this point in the summer -- in 1964.

S&P 500 Snubbing Dire ViewWhat’s keeping stocks aloft? As usual, the answer is corporate America’s earnings machine.

...the equity market is not the economy. If you compare the two, the equity market has massive technology in it, a lot less small-caps. Those earnings are super defensive to a no-GDP-growth scenario.”

In the eyes of analysts who follow individual companies, profit growth is set to slow, but at roughly 10% in each of the next two years, that would still top the historic rate of 6% annually.

Profit margins, which just reached a record high, are expected to increase over the next years, analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence show.

To Paulsen, chief investment strategist at Leuthold, this boom cycle is just starting.

50 years ago, on August 15, 1971, President Richard Nixon shocked the financial world by ending the convertibility of the dollar to gold, upending the monetary and currency exchange system that had been in place since 1944. This week Nick Sargen, author of Global Shocks, joins us for a WEALTHTRACK podcast to explain the consequences of that momentous decision which are still being felt today.

© 2015 Mutual Fund Observer. All rights reserved.

© 2015 Mutual Fund Observer. All rights reserved. Powered by Vanilla