It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

https://www.retailinvestor.org/pdf/Bengen1.pdfThe withdrawal dollar amount for the first year (calculated as the withdrawal percentage times the starting value of the portfolio) will be adjusted up or down for inflation every succeeding year. After the first year, the withdrawal rate is no longer used for computing the amount withdrawn; that will be computed instead from last year's withdrawal, plus an inflation factor.

https://www.morningstar.com/articles/945008/be-thankful-that-you-dont-compete-against-vanguard[A]lthough academic theory states that performance should be risk-adjusted, investors tend to pay greater attention to unadjusted returns--not without reason. Academic theory assumes the use of leverage, but few mutual fund owners will ever borrow to purchase more shares. They therefore may be pardoned for favoring the bottom line...

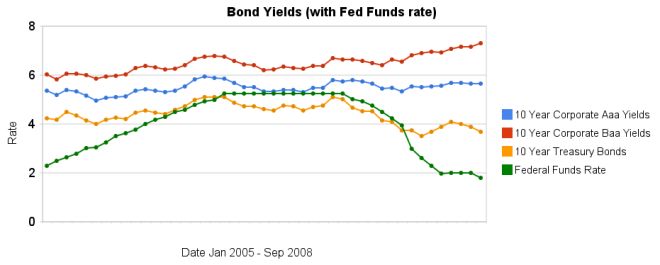

Kitces, incorporating CAPE P/E 10 data, concluded that the safe withdrawal rate is never less than 4.5%, and can be increased if the ratio at the start of retirement is under 20.It does indeed seem that retiring at times with particularly low bond yields, which can be expected to increase over time, may not favor rising equity glidepaths during retirement. It essentially causes the retiree to lock in low bond returns and even capital losses on a bond fund as bond yields gradually increase (on average) over time.

Now he says SP500 performance will be around 7%.Inflation directly affects the periodic withdrawals, as it is assumed that dollar withdrawals are increased annually by CPI. If inflation is high, it results in rapidly increasing withdrawals. ... the inflation trend hints at a reliable cause-and-effect relationship. As inflation (defined as the trailing 12-month Consumer Price Index at retirement) increases from top to bottom, SAFEMAX correspondingly declines.

Also on point regarding predictions, he writes: "if you have strong feelings that the inflation regime will change in the near future, you can choose another [presumably more conservative] chart".I should also issue the usual cheerful disclaimer that this research is based on the analysis of historical data, and its application to future situations involves risk, as the future may differ significantly from the past. The term “safe” is meaningful only in its historical context, and does not imply a guarantee of future applicability.

2) "Most of us don't have the time or desire to do the research and then jump in and out of lower-rated and often newer bonds fund." How about admitting it's not about time at all. Investing was always may passion, I do research regardless if I trade or not. When I do it specifically for trading it takes me maybe an hour per month. In the period of 2000-2010 when I traded less often it took me about an hour every several months. The bigger and more important question is...do you see better results?Historically, when stock prices are rising and more people are buying to capitalize on that growth, bond prices have typically fallen on lower demand. Conversely, when stock prices are falling and investors want to turn to traditionally lower-risk, lower-return investments like bonds, their demand increases, and in turn, their prices.

Bengen says based on the current environment he thinks a new retiree should be safe if they start with a withdrawal rate of…no more than 5%.

“That’s what I use myself,” Bengen told me when we spoke by phone.

....retirees right now have one saving grace: Very low inflation.

© 2015 Mutual Fund Observer. All rights reserved.

© 2015 Mutual Fund Observer. All rights reserved. Powered by Vanilla