It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Bank of America Calls CBDCs ‘More Effective’ Than Cash in Research NoteBank of America (BofA) called central bank digital currencies “a much more effective payment system than cash,” in a research paper published Wednesday.

...CBDCs could “replace cash completely in the (distant) future.”

CBDCs qualified as money “by allowing store of value and being a unit of account and means of exchange,” differentiating them from cryptocurrencies that “do not meet these criteria. “Since they are traded, they could be seen as an asset class,”

CBDCs could lessen the need for stablecoins, noting that the latter could “present a material financial stability risk during times of market stress when there may be a crypto to fiat currency run.”

https://blocktower.substack.com/Originally known as “open finance”, the advent of DeFi represents yet another innovation on the rapidly evolving world of cryptoassets and blockchain technology. As with most new innovations, there is the growing litany of new announcements, innovative solutions and industry mania as these offerings progress throughout the landscape. For many, it seems a chance for new business models and rapid wealth creation. For the more sober minded, it is yet another step in the swift transformation happening across financial markets, and indeed across all industries in the global economy. As always, change and disruption require us to revert back to first principles. And these first principles demand that we ask the question: why? Why decentralized finance? What problems does it solve? And what, in truth, do we actually mean by “decentralized finance”?

These inquiries bring us to the motivation for this publication. It is our hope that this primer can offer a proposed definition for DeFi, in all of its forms, as well as share with the reader current and future DeFi use cases. It also touches on the challenges of DeFi, not least of these being the uncertain and evolving regulatory and legislative challenges coming to the fore. As a product of the WSBA Accounting Working Group, this work also delves into the

very complex accounting considerations that DeFi poses, both now and in the future. Finally, we conclude with some thoughts on what the future holds and offer some resources to keep pace with this future.

It is our goal that this be the first in a series of thought leadership publications that continue to aid the advancement of the cryptoassets and blockchain ecosystems, the accounting profession and global markets around the world. We welcome your thoughts and feedback and hope that you find this document informative as well as useful.

About Fed Now (Federal Reserve website)[T]here are two reasons to be a little bit skeptical about some of these [CBDC benefit] claims. The first reason is we could achieve the same benefits with a more traditional approach. For example, you could also offer people bank accounts simply by subsidizing them. And the Fed is already planning to speed up payments by introducing a new, real time payment system called Fed Now that will come online by 2023.

The second reason to be a little bit skeptical is that some of these benefits require a more radical version of a CBDC than any central bank is actually planning to introduce for now. For example, no central bank is planning to completely phase out cash, so you can't really claim that as a benefit.

...

[A]dvanced economy central banks are more focused on improving the safety and robustness of the payment system, although most consider it an open technological question whether or not a CBDC would really achieve this. I think this is basically how the Fed is thinking about it.

https://www.bls.gov/cex/csxgloss.htm#cueither: (1) all members of a particular household who are related by blood, marriage, adoption, or other legal arrangements; (2) a person living alone or sharing a household with others or living as a roomer in a private home or lodging house or in permanent living quarters in a hotel or motel, but who is financially independent; or (3) two or more persons living together who use their income to make joint expenditure decisions. Financial independence is determined by the three major expense categories: Housing, food, and other living expenses. To be considered financially independent, at least two of the three major expense categories have to be provided entirely, or in part, by the respondent.

https://www.bls.gov/cex/csxgloss.htm#refperReference person - The first member mentioned by the respondent when asked to "Start with the name of the person or one of the persons who owns or rents the home." It is with respect to this person that the relationship of the other consumer unit members is determined.

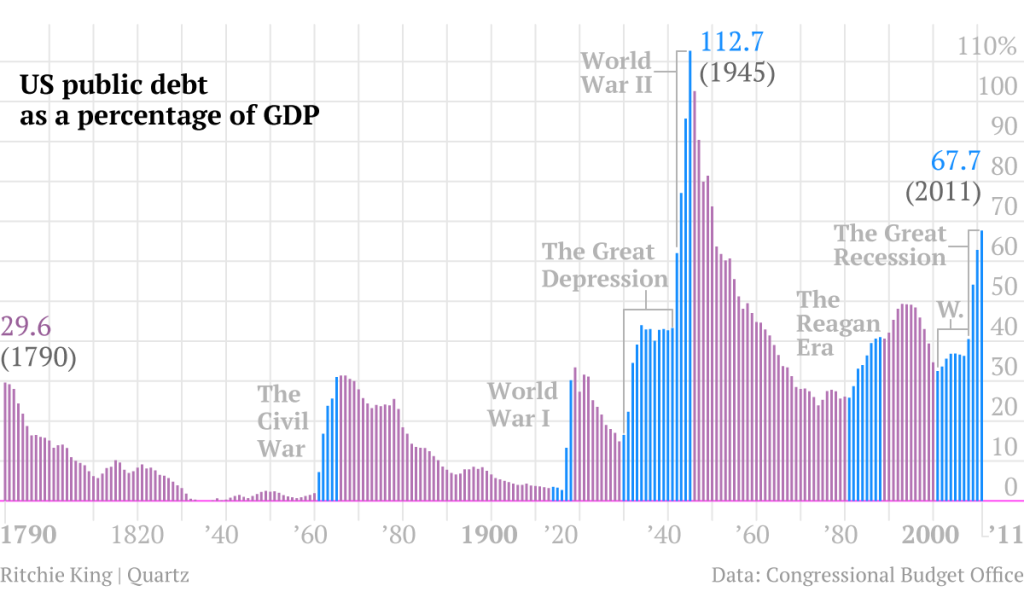

https://reuters.com/world/us/every-time-its-messy-us-again-approaching-debt-ceiling-2021-07-21/The U.S. Congress will learn on Wednesday when the federal government will likely run out of money to pay its bills, setting the stage for the latest in a long series of fights over what is known as the debt ceiling.

A failure by Democrats and Republicans to work out differences over whether government spending cuts should accompany an increase in the statutory debt limit, currently set at $28.5 trillion, could lead to a shutdown of the federal government -- something that has happened three times in the past decade.

On July 31, the Treasury Department technically bumps up against its statutory debt limit. Much like a personal credit card maximum, the debt ceiling is the amount of money the federal government is allowed to borrow to meet its obligations. These range from paying military salaries and IRS tax refunds to Social Security benefits and even interest payments on the debt.

Remeber that in 2011, Republicans launched a battle over the debt limit and federal spending, which led to the first-ever Standard & Poor's downgrade of the U.S. credit rating -- a move that reverberated through global financial markets.

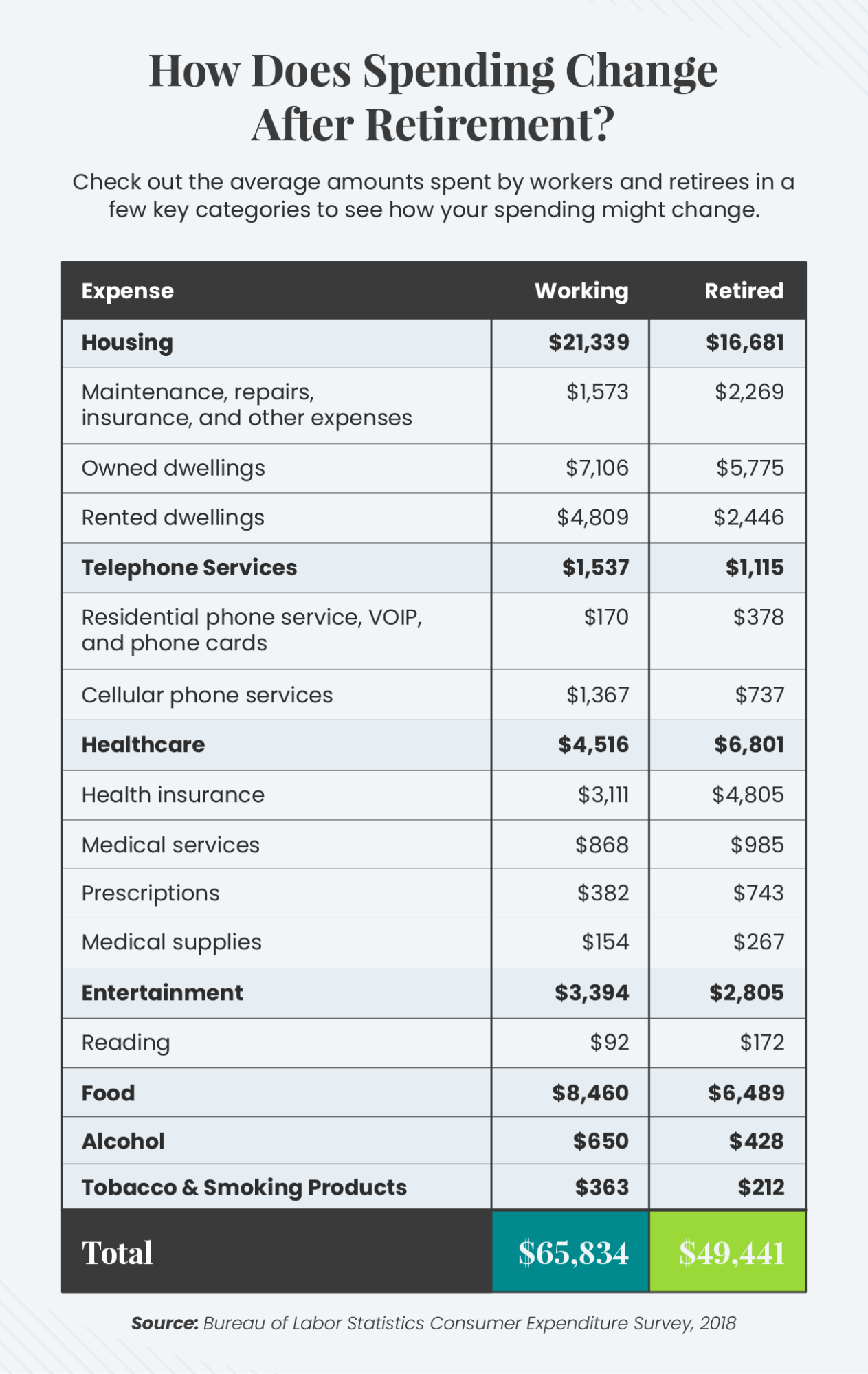

https://annuity.org/retirement/retirement-statistics/Three-quarters of Americans agree the country is facing a retirement crisis, making research around the topic more relevant than ever. We dug into the data on every angle of retirement and compiled the most important statistics below. Read on to learn about what today’s retirees face, from financial challenges to lifestyle decisions and more.

© 2015 Mutual Fund Observer. All rights reserved.

© 2015 Mutual Fund Observer. All rights reserved. Powered by Vanilla