Dear friends,

Welcome to May, traditionally, the month in which to sell in!

These first few weeks of May are an odd time on campus. My seniors are scrambling for jobs (or antidepressants), the juniors are teeing up internships, and the youngsters are … well, mostly wondering what just happened to them?

It’s a time of year that brings out the best, and the worst, and the oddest of them. On May 7, hundreds of our students gather to present their work to a campus and community audience. Not classwork, just work. Stuff they’re passionate about. One of my students, Adele, presents “Minimalism, Meaning, and Machines: Einstein on the Beach and the Art of Processing Technological Innovation,” which looks at the Philip Glass opera (you did know it was a famous opera, right?) using, in part, the issues we discussed in Communication and Emerging Technologies about technological determinism and the fear of new technology. A bunch of presentations will build off the work students did last summer with the University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and Baylor College of Medicine, “Commonly Used Measures of Cancer Impact: What are we measuring?” as an example. Quilting in Appalachia, The Gods in Racine (no, not Racine, Wisconsin, Racine the French playwright who is also the focus of Sado-Masochism in the Works of Racine, which is okay because it’s the French department and the French are … very French sometimes). We cancel all our classes for the day to engage in The Celebration of Learning.

And at the same time, I got a lovely note from Zoe that said, “Hey, Snowball, just a heads up. I’m not coming to class today. I have three weeks left in my time at college, and today is too beautiful to spend inside.” Glanced at the record to confirm what I already knew (she could skip the rest of the semester without noticeably reducing her chance for an “A”) and nodded.

Professors once gave lip service to the argument that “learning takes place everywhere, not just in the classroom.” I’ve always been delighted that Augustana often acts like they really believe it.

In this issue of the Observer …

Lynn Bolin has adopted a pretty cautious “risk off” stance amid economic uncertainty. Tariffs and their potential impacts emerge as a central concern, with Lynn drawing parallels to 1970s stagflation. Those concerns tie together both of his essays this month.

In “My Investment Strategy For 2025,” Lynn outlines his investment approach amid high market volatility and uncertainty. He maintains a traditional 60/40 stock/bond portfolio (ranging from 55-65% in stocks) with small quarterly adjustments based on volatility-adjusted momentum. His investment model, which incorporates 30 years of fund data, recommends a “risk off” stance since mid-2022. Despite the S&P 500’s recent gains, he identifies concerning trends in consumer health, corporate performance, and equity valuations. With parallels to 1970s stagflation, he’s increasing allocations to short-term investment-grade and inflation-protected bond funds while maintaining stability for withdrawals.

In a market subject to rather sudden reverses, Lynn also addresses “Trending Funds YTD 2025.” He reviews top-performing funds across bonds, mixed assets, and equities using his proprietary ranking system based on MFO Premium data. Bond rankings show strength in short-term investments and inflation-protected securities, and he’s considering replacing high-yield funds showing negative YTD returns. In mixed assets, alternative global macro funds like Eaton Vance Global Macro Absolute Returns stand out as potential “Risk Off” diversifiers. Equity rankings demonstrate international and global funds significantly outperforming domestic options. As tariff impacts become clearer by June, Lynn is focusing on reliable fixed income for the next 5-10 years while considering tax-efficient international equity funds.

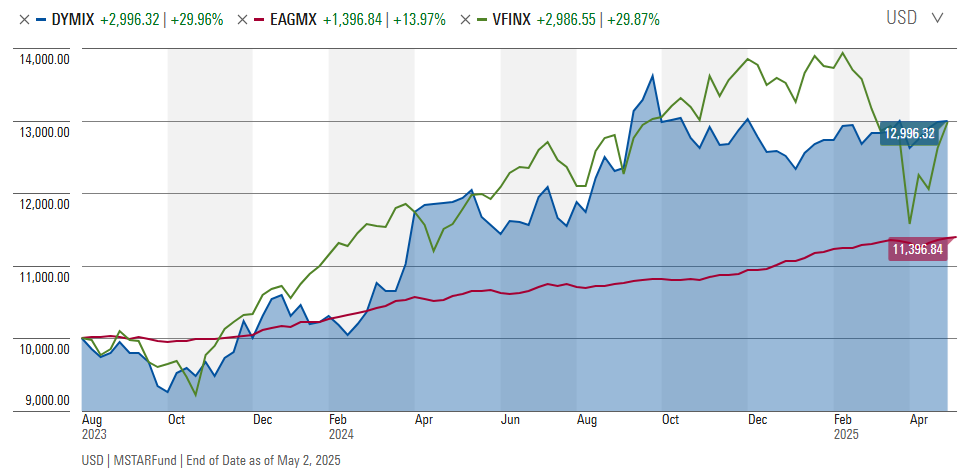

I share Lynn’s anxiety about the consequences of policy chaos on the markets, and so profiled Dynamic Alpha Macro Fund, a younger entrant in the global macro category. The fund matches a 50% equity stake with a 50% macro-driven futures trading strategy. The results have, so far, been exemplary: returns since inception that beat the S&P 500 with a negligible correlation to it. The picture of the trio – Eaton Vance (red), Dynamic Alpha (blue), and the S&P 500 (roller coaster) since Dynamic Alpha’s launch – looks like this.

There’s one clear beta story. One clear alpha story. And two funds worth considering if you’re not convinced that it’s all going to be fine and dandy any day now.

Dynamic Alpha is part of a larger discussion that we’ve been pursuing, Building a Chaos-Resistant Portfolio. We debuted the term in December 2024 and have pursued articles, almost monthly, on the challenge of managing through crazy times. This month, we update on how the funds and strategies we’ve discussed have served their investors. (Spoiler alert: pretty well, all things considered.) As a sort of public service, we also offer a sneak peek at Lewis Braham’s Barron’s essay, “The Chaos-Resistant Fund Portfolio.”

We also share a Launch Alert for T. Rowe Price’s newest offering in its Capital Appreciation suite for funds and ETFS: T. Rowe Price Capital Appreciation Premium Income ETF. It offers income, some growth, and exceptional stability.

Our colleague Charles Boccadoro updates folks on new fund flow analysis, which will now offer daily updates through the FLOW tool. (At $120/year, his site really is the most radically underpriced – albeit quirky – fund and ETF data site in existence. Unlike Morningstar’s online tools, Charles has offered side-by-side, metric-by-metric analyses of funds, ETFs, and closed-end funds since Day One. The data and analytics are incredibly rich.)

And The Shadow wraps things up in Briefly Noted, noting briefly, as is his wont, a huge series of fund-to-ETF conversions which seem to be eclipsing the impulse to liquidate funds.

Things that make me pause

“Necessities” don’t mean quite the same thing to all of us. Credit Karma surveyed 2,000 American adults in April 2025, seeking to learn how they might respond to a world with higher expenses and more constrained income. Across the board, 80-90% of all age groups allowed that they would “strongly consider” cutting back on nonessential spending.

The difference, by generation, is what’s “essential.”

Fifty-six percent of Gen Z and 59 percent of Millennials said spending on hobbies and interests is a necessity, not a luxury. And nearly half of young consumers (51 percent of Millennials and 45 percent of Gen Z) said they would rather reduce long-term savings than give up certain lifestyle experiences including going out to eat, travel and fitness memberships. (Alexandre Pastore, “Gen Z and Millennials Are Redefining What Items Are ‘Necessities’ Amidst Economic Uncertainty,” 5/5/2025)

A Lending Tree survey reported in Fortune notes that one-quarter of Americans are now buying their groceries on credit (paid access, sorry, 4/28/2025). One budget move has been to end psychological therapy appointments; the most popular use for AI chatbots in 2025 is now “therapy and companionship.”

The 19 richest American households got richer, $1,000,000,000 richer in 2024. One trillion dollars richer during Mr. Biden’s last year in office, which might raise questions about why so many of them were so upset with him. The 19 households include some familiar names, such as Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, Jeff Bezos, Stephen Schwarzman, and Warren Buffett. The Wall Street Journal framed it this way:

The wealthiest have gotten richer, and control a record share of America’s wealth. New data suggest $1 trillion of wealth was created for the 19 richest American households alone in 2024. That is more than the value of Switzerland’s entire economy. (“$1 Trillion of Wealth Was Created for the 19 Richest U.S. Households Last Year,” WSJ, 4/23/2025)

Rich investors offering forecasts need to be approached cautiously. Their statements reflect professional expertise, personal bias, and the inevitable urge to “talk their book.” That said, rather a number of top-tier investors have shared storm warnings. Paul Tudor Jones said that even if Trump walks back his tariffs, markets are headed “to new lows.” (“A billionaire hedge fund manager has a chilling stock market warning,” Quartz, 5/6/2025). Ray Dalio argues that we face “something worse than a recession” (Shannon Carroll, “Ray Dalio is worried about ‘something worse than a recession’,” Quartz, 4/14/2025)

Deutsche Bank argues that the fragility of the US markets is heightened by “the end of American exceptionalism.” Traditionally, the US has offered the world’s safest investments – the US dollars, Treasuries – because America had an unprecedented reputation for accepting its role as the grown-up in the room. As we look more like post-war Italy, global investors find it easier to imagine a flight, perhaps precipitous, from US investments (“3 market signals that could be setting the stage for another correction,” Business Insider, 4/29/2025, also Pictet Asset Management, “The twin sell-off that signals a break with the past,” 4/2025). Institutional voices such as Moody’s Analytics, JP Morgan, and Apollo Capital place the prospect of a US recession in the year ahead at 50-90%. The special problem is the macro-economy environment: Callie Cox, the chief market strategist at Ritholtz Wealth Management, worries that low growth and rising prices would hamstring the Fed, which investors have counted on for a generation to save their cookies from the fire. (Callie Cox, “America is on the verge of stagflation,” Business Insider, 4/28/2025).

Bloomberg, not a reactionary bunch, published findings from Bespoke Capital that substantiate a “sell in May” strategy. “Investing in a fund that debuted in 1993 and tracks the S&P 500 during the May-October period yielded a cumulative return of 171%, compared to a 731% gain for November-April,” concluding “ the risks are skewed toward the S&P 500 suffering another big decline next month” (Bloomberg Markets Daily, 4/30/2025).

I always take the folks at the Leuthold Group seriously; they’re data-driven, and their data sometimes signals the prudence of caution even while the party rolls. Their early May research releases: the market’s latest bounce is consistent with bear market rallies, valuations have now returned to epic levels, and cracks seem to be deepening.

I am intensely aware of the success of economists in accurately predicting eight of the past three recessions. And still, increasingly, I hear the voice of Sgt. Esterhaus from Hill Street Blues, who finished his roll call every week with the same prescient advice: “Let’s be careful out there.”

I am intensely aware of the success of economists in accurately predicting eight of the past three recessions. And still, increasingly, I hear the voice of Sgt. Esterhaus from Hill Street Blues, who finished his roll call every week with the same prescient advice: “Let’s be careful out there.”

Farewell to The Great Men

I know, I know, it’s all over the news and there’s precious little to add.

Pop is gone.

Pop is gone.

Gregg Charles Popovich has stepped down after 29 years as the head coach of the San Antonio Spurs, which made him the longest-tenured coach in all of professional sports. In that stretch, he won five league championships, over 1400 wins, and had 22 consecutive winning seasons. He is, by all accounts, a remarkable person and a champion for the people in San Antonio. His decision to step aside as a mere stripling of 76 was occasioned by a mild stroke in November 2024 and fainting in a restaurant in April 2025. He will be missed.

The other retirement news of the month, in case you’d missed it while following the NBA, is Warren Buffett’s retirement announcement, apparently not shared in advance with his own successor. The announcement came during Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting on May 3, 2025.

The other retirement news of the month, in case you’d missed it while following the NBA, is Warren Buffett’s retirement announcement, apparently not shared in advance with his own successor. The announcement came during Berkshire Hathaway’s annual meeting on May 3, 2025.

Berkshire’s stock promptly fell 4%, only slightly ironic given Mr. Buffett’s lifelong devotion to investing for the long-term (really, did anyone think Mr. B. would actually carry out his threat to continue running Berkshire from beyond the grave?) and his emphasis on fundamentals rather than personalities.

Berkshire’s original investors, who had held since the start, would pocket a gain of 5,500,000%, about 140 times the gain in the S&P 500. (Not 140% of the gain, 14,000% of the S&P’s rise). Even the latecomers who joined in 1980 would have seen a 296,000% gain. Millennial investors, those staggering in as the Dot.com became the Dot.bust pocketed a 1500% rise, just short of triple the S&P 500’s gain in the same period.

If I had to share advice on how to think about Berkshire’s future based on Mr. Buffett’s career, I might invent the following quotation and attribute it to him (because that’s how the internet works):

The greatest companies outlive even their greatest leaders; true wealth isn’t built by timing departures, but by owning excellence through transitions.

Warren Buffett and Isoroku Yamamoto

One of the habits that distinguishes great leaders from those who grind and trash is a tendency to read widely, incessantly, and with an engaging curiosity. That’s true, most famously, of Bill Gates and of Mr. Buffett’s other half, Charlie Munger.

Mr. Buffett released what might be his final book recommendation list at Berkshire’s May meeting. It contained 27 titles, of which a dozen are books by or about Mr. Buffett and his firm. Here’s what else Mr. Buffett thinks you would profit from reading:

Capital Allocation: The Financials of a New England Textile Mill 1955–1985 by Jacob McDonough

The Great Crash: 1929 by John Kenneth Galbraith

Where Are the Customers’ Yachts? by Fred Schwed Jr.

Business Adventures: Twelve Classic Tales from the World of Wall Street by John Brooks

The Intelligent Investor by Benjamin Graham and The Intelligent Investor (Revised Edition) by Jason Zweig

The Little Book of Common Sense Investing: 10th Anniversary Edition by John C. Bogle

The Ten Commandments for Business Failure (“I like to study failures,” WB) by former Coca-Cola CEO Donald R. Keough

Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion and Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade, both by Robert Cialdini. These might be the bestselling books ever on the science of persuasion, with simple and actionable insights.

Unscripted: The Epic Battle for a Media Empire and the Redstone Family Legacy by James Stewart and Rachel Abrams

Americana: A 400-Year History of American Capitalism by Bhu Srinivasan

Getting There: A Book of Mentors by Gillian Zoe Segal, snippets about working with great people, including Mr. Buffett

Running with Purpose: How Brooks Outpaced Goliath Competitors to Lead the Pack by Jim Weber, a leadership tale from the CEO of Brooks Running Company, which Mr. Buffett bought in 2012

Trillion Dollar Triage: How Jay Powell and the Fed Battled a President and a Pandemic—and Prevented Economic Disaster by Nick Timiraos, the most contemporary book on the roster, published in 2022.

My own reading, in leadership and history, has gone in a different direction lately. The Reluctant Admiral: Yamamoto and the Imperial Navy by Hiroyuki Agawa is widely regarded as one of the most nuanced and insightful biographies of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. The book draws heavily on original sources, including Yamamoto’s own letters and interviews with those who knew him, to present a portrait of a complex, deeply conflicted leader

My own reading, in leadership and history, has gone in a different direction lately. The Reluctant Admiral: Yamamoto and the Imperial Navy by Hiroyuki Agawa is widely regarded as one of the most nuanced and insightful biographies of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto. The book draws heavily on original sources, including Yamamoto’s own letters and interviews with those who knew him, to present a portrait of a complex, deeply conflicted leader

Traditionally, Yamamoto has been the face of Japanese aggression in the Pacific War, and yet the picture is a lot more complex. As commander of the combined fleet, Yamamoto coordinated and executed the attack on Pearl Harbor. As reports of success after success flooded in, “the staff officers could not conceal their jubilation; Yamamoto alone, apparently, remained sunk in apparent depression.”

That might be explained by Yamamoto’s single most quoted prediction:

“If I am forced to wage war with the United States regardless of the consequences, I will run wild for six months, but I have no confidence in the years after that,” a statement apparently made to Prime Minister Prince Fumimaro Konoye, late 1940.

Yamamoto knew America and knew the odds and calculated that his only chance was a six-month spree of terror that might so stun the Americans that they would conclude that resistance was not worth the cost. If Americans stood firm after the six-month assault, Japan, he knew, would fall. That became a self-fulfilling prophecy. By June 1942, when his indecision at the Battle of Midway led to catastrophe, it was clear that Yamamoto had no long-term plan. Destroy as much as possible, as fast as possible, and then … and then? No idea. Improvise.

I wonder if Americans, in May of 1942, had any idea of how brittle their apparently indestructible foe was?

[edited to correct dates. Thanks to D. Moran for the catch!]

If you’re so smart …

“Why aren’t you rich?”

This familiar challenge reveals three curious truths about American culture. First, it presumes wisdom’s natural expression is wealth—that your intellect should be measurable by your investment portfolio. Second, it exposes our impoverished definition of “richness.” While I nurture thoughts, cultivate relationships, touch thousands of lives, and tend my garden, none register as “wealth” without the validation of a brokerage statement.

Most tellingly, we never pose the reverse question: “If you’re so rich, why aren’t you smart?”

This equation of wealth with wisdom is quintessentially American. Cultures worldwide contemplate both riches and sagacity, yet none so persistently conflates them. Americans uniquely generalize from great fortune to great insight, willingly overlooking moral failings or intellectual shortcomings among the ultra-wealthy.

Earlier this month, I published an essay examining this question at LinkedIn. It has been nibbling at my brain for a long time, highlighted by the utterly, entirely predictable March of the Billionaires to kneel before the throne.

Validity notwithstanding, it seems a bit far afield from MFO’s mission, and so we thought it better to link to it here (it should open in a new tab for you) rather than republish it.

I’ll walk through three arguments with you, followed by a brief coda and suggestions from where you might learn more if you’re so disposed. Here are the arguments:

- The ultra-rich really are different from the rest of us.

- The factors that allow them to become wealthy create an aversion to the messiness of democracy and an allure to authoritarianism.

- That never ends well, for them or for us.

- Coda: There are honorable exceptions, principled, thoughtful people who acquired (and often dispensed) great wealth without losing their principles.

There’s a bunch of academic research behind all of this. I’ve tried not to burden you with it, but would be happy to share more sources if you’re curious, masochistic, or curiously masochistic.

Thanks, as ever …

To our faithful subscribers, the good folks at S&F Investment Advisors, Wilson, Greg, William, William, Stephen, Brian, David, Doug, and, most recently, Altaf. If you’d like to join them in their good work, you might click on the “Support Us” page.

Special thanks this month to Anitya, Don G (I humbly and entirely endorse your priorities when it comes to philanthropy: serve those in distress and work to rebuild a sane future), and Thomas from Moscow (Idaho, that is!)

And to Mr. Buffett and Mr. Munger and Mr. Popvich and all of the good folks who stuck it out, eschewing getting rich quick or quick wins for long careers that shaped the lives of investors and young athletes, in powerful ways.

And thanks to all of you for sharing fourteen years with us. MFO launched in May 2011 with the promise of carrying on the mission of its predecessor, FundAlarm: to speak with a human voice, humbly and without commercial pressure, to help investors navigate a world ridden with marketing hype, financial shenanigans, and easy answers.

It’s never been our goal to be the source of all the answers. Our goal is to help empower the better angels of our nature, the impulses to charity and justice, reflection, and deliberation. Our hope, in this issue and in the 168 that preceded it, is that your day is just a bit better for the presence of one voice and one message: “Take a deep breath. We can think this through together.”