No Exit From Bond Funds ? FYI: Copy & Paste 6/21/14:

Regards,

Ted

A well-thought-out exit strategy is vital to the success of a mission, as the recent events in Iraq demonstrate quite dramatically.

Given that unfortunate example, it might be well that the Federal Reserve appears to be thinking about the consequences of the end -- and eventual reversal -- of its massive experiment in monetary stimulation. Last week, the Financial Times reported that the central bank is mulling exit fees on bond mutual funds to prevent a potential run when interest rates rise, which, given the ineluctable mathematics of bond investing, means prices fall. Quoting "people familiar with the matter," the FT said that senior-level discussions had taken place, but no formal policy had been developed.

Those senior folks apparently didn't include Fed Chair Janet Yellen. Asked about it at her news conference on Wednesday, she professed to be unaware of any discussion of bond-fund exit fees, adding that it was her understanding that the matter "is under the purview" of the Securities and Exchange Commission.

That nondenial denial leaves open the possibility that some entity in the U.S. financial regulatory apparatus is indeed mulling bond-fund exit fees. The Financial Stability Oversight Council established by the Dodd-Frank legislation oversees so-called systemically important financial institutions, or SIFIs, which include nonbank entities. And, indeed, the FSOC has considered designating asset managers as SIFIs, as Barron's has noted previously ("Why Fund Firms Aren't Too Big to Fail," June 2).

To Dan Fuss, the longtime chief investment officer at Loomis Sayles, the exit-fee story seemed like a "trial balloon." But, he added, "from a practical point of view, I don't think it has a snowball's chance in hell, given the resistance from the retail distributors of mutual funds."

Still, he continued, "it won't make me very popular -- but I think it's a good idea." That's from someone whom I would call the Buffett of bonds. Like his fellow octogenarian in Omaha, Fuss has lived through more than a few market paroxysms and has been able to take advantage by putting money to work opportunistically during panics. Unlike the head of Berkshire Hathaway, Fuss also has had to contend with outflows from his flagship Loomis Sayles Bond fund and the firm's other corporate-bond funds, as happened during the 2008 financial crisis. For staying the course during those dark days, Fuss was named Morningstar's Fixed-Income Manager of the Year in 2009.

The latter vantage point no doubt informs his endorsement of the concept of exit fees for bond funds. As the FT quoted former Fed Governor Jeremy Stein, bond funds give investors "a liquid claim on illiquid assets." That is most acute for open-end, high-yield bond funds, Fuss says, and extends to exchange-traded funds "in less liquid areas," which would apply to junk-bond and bank-loan ETFs.

It is a fact of financial life that most bonds are relatively illiquid, in part owing to their bespoke nature; every bond has its own unique coupon rate and maturity, plus possible features such as call options, seniority, and security, even among the same issuer. In contrast, every common share of most companies is identical (with exceptions for stocks with multiple share classes). Multiple buyers and sellers of the same item is economists' definition of a perfect market, as with a commodity such as wheat. Big, listed stocks come close; bonds, given their granular nature, don't.

The problem of liquid claims on illiquid assets is etched into American culture in the Christmas-time classic film, It's a Wonderful Life. Faced with a run on his savings-and-loan, Jimmy Stewart pleads with his depositors that there's little cash in the till because the money is invested in the townfolks' mortgages and businesses. The practical solutions to this conundrum: deposit insurance and having central banks act as lenders of last resort.

Those facilities don't apply to bond funds now, and didn't to money-market funds in 2008. Following the Lehman bankruptcy, the Reserve Fund "broke the buck," with its net asset value falling below $1 a share. The resulting run on that money fund and others exacerbated the crisis as this source of funds to the money market dried up.

Officials fear that bond funds could represent "shadow banks," the FT writes, intermediaries subject to runs but without resort to the backstops available to banks. Yet, the irony is that the rush into bond funds is a result of the Fed's own policies of pinning interest rates to the floor, which spurred investors to seek income wherever they could find it. As a result, bond funds have ballooned to $3.5 trillion -- with a T -- according to the most recent data from the Investment Company Institute. That's close to the Fed's securities holdings, which total $4.1 trillion.

Statistical evidence of that reach for yield comes from a research paper from Bank of Canada economists Sermin Gungor and Jesus Sierra (which was passed along by Torsten Slok, chief international economist at Deutsche Bank Securities).

Not surprisingly, low rates spurred bond funds to increase the credit risk in their portfolios to boost returns. Canadians, it's safe to assume, are no less desirous of maintaining investment income than are their neighbors to the south.

But with investors having stampeded into bond funds, would exit fees be effective at keeping them from stampeding for the exits at the first sign of higher yields and lower prices? Research suggests otherwise. And, ironically, it comes from within the Fed itself.

According to a New York Fed staff paper by Marco Cipriani, Antoine Martin, Patrick McCabe, and Bruno M. Parigi (and surfaced by Zerohedge.com), impediments to redemptions could actually spur bond-fund investors to sell first and ask questions later. In other words, exit fees or "gates" to discourage redemptions could backfire.

In Sartre's No Exit, hell is famously defined as "other people." The crisis that might ultimately await bond-fund investors is the prospect of being stuck with their fellow shareholders as yields rise and prices fall, rather than paying a ransom to escape. The existential choice facing bond-fund investors is whether to stay and face that prospect, or exit while they can -- if they are not prepared for a long-term commitment.

THE SUMMER SOLSTICE just arrived in the Northern Hemisphere, putting the sun highest in the sky. And, appropriately, the major stock-market averages closed the week at records, notably the Standard & Poor's 500 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average, which approached another round-number milestone: 17,000.

The latest liftoff came after Fed Chair Janet Yellen made clear that neither rising inflation nor soaring asset prices would deter the central bank from monetary tightening. She called the uptick in the consumer-price index, which is running above the Fed's 2% inflation target (admittedly using a different gauge, the personal consumption deflator), "noisy." But it's hurting Americans' budgets more than their ears.

In essence, Yellen endorsed the view espoused by hedge fund mogul David Tepper a couple of years ago, that the course of monetary policy "depends" on the economy. If growth is sluggish, policy will remain accommodative, which is bullish for risk assets. Interest-rate hikes won't come until there is strong growth, which also is bullish. And as long as the monetary authorities have their back, investors have little reason to worry. So, volatility premiums collapsed in the options market; if the Fed is offering free insurance, why pay for it with hedges?

This benign environment is spurring investors to vote with their portfolios. Michael Hartnett, chief investment strategist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, notes a big, $13 billion inflow into equity mutual funds in the latest week and the first outflows from bond funds, totaling $2.3 billion, in 15 weeks.

Have fund investors finally been infused with animal spirits? Hard to say, given that the equities data showed a record influx into utilities, some $1.2 billion, which Hartnett suggests indicates some chasing of that group's torrid past performance, up some 16% in 2014. Utility stocks are viewed as first cousins to bonds; income is their primary allure, but with the prospect of dividend growth, that should trump fixed coupons.

Still, public participation in the stock market has yet to evince irrational exuberance, notes David Rosenberg of Gluskin-Sheff. In other words, the market has yet to violate rule No. 5 of Bob Farrell, the legendary market analyst at Merrill Lynch -- that the public buys most at the peak and least at the lows.

Tops, Rosenberg explains, typically show a melt-up of a heady 11% over 30 days, which represents a first peak. A pullback lures neophytes and momentum chasers "hook, line, and sinker," to form twin peaks. That pattern was apparent in November 1980; August-October 1987; June-July 1990; April-September 2000; and July-October 2007, he points out.

To quote every parent of young kids, we're not there yet. But, Rosenberg relates, there also is Farrell's rule No. 7: Markets are strongest when they are broad and weakest when they narrow to a handful of blue chips.

Another veteran market maven, John Mendelson of International Strategy & Investment Group, last week pointed to the declining number of New York Stock Exchange stocks trading below their 200-day moving averages, a sign of waning momentum in the broad market that he says represents a "negative divergence." That is especially so with the major averages notching records.

So, easy money continues to float Wall Street's yachts. Belatedly, the gold market also has noticed, with the metal surging 3% on the week, and mining stocks leading the advance. Gold may be sending the true signal, above the supposed noise from the inflation indexes.

M*, Day 2: Bill Gross's two presentations "I find it somewhat puzzling why a few MFO members are so short-tempered and even hostile towards Morningstar’s limitations, errors, and costs.".

Here's the thing: I'm not particularly upset by any of M*'s issues. I look at things like S & P analyst reports, M* reports and other things as sources of information that I can take a little bit from here, a little bit from there and make a larger decision.

I do think that people (not saying towards anyone here) are giving a little too much slack towards companies whose products decrease in quality and/or quality. I think - in some ways - people are a little too forgiving. I think people also are moving away from quality if it means convenience in some things (photography, music, etc) but that's another story.

When the product deals with people's money - such as investment research - people are going to be harsh critics. It shouldn't be surprising when there's money at stake.

"It is far too easy to be a constant critic. The bad is overemphasized while the good is swept away without acknowledgment. If the Morningstar presentations are too dull or too inept, the answer is simple enough: abandon the ship."

It's also far too easy to be a pollyanna and then have the convenient "whocouldaknown?" excuse when things go wrong. There is a happy medium, although finding that medium may take a great deal of trial and error.

"I’m not advocating the elimination of skepticism. At some point, it detracts from permitting a timely decision from being made."

Sometimes skepticism does save people from making rash decisions that they regret later. After the financial crisis, I think people aren't skeptical enough - everyone just wanted things to be rebooted back to a few years prior without the unpleasantness of actually trying to make it so something similar wouldn't happen again. History is bound to repeat itself because having to learn from mistakes is no fun.

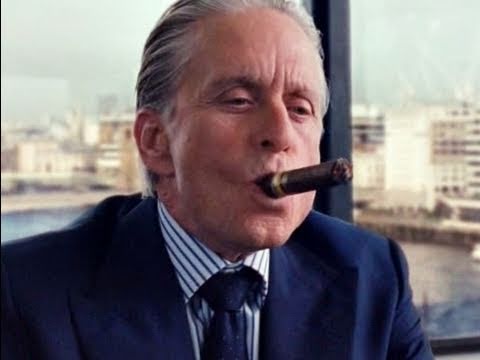

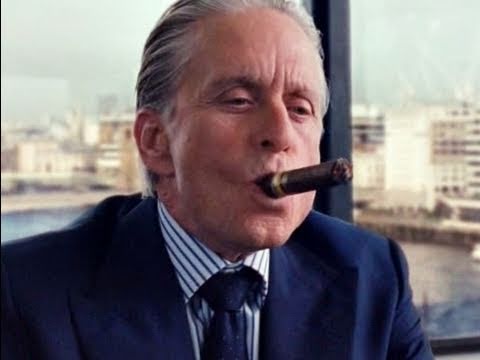

If Madoff was out of prison tomorrow and started a fund again, I bet he'd have willing investors. It's the second "Wall Street" movie. The Gekkos of the world go in front of an audience of those just willing to believe and they listen and clap and don't ask questions. 2008 happens and a few years later, they're sitting, clapping and hanging on every word yet again.

Is there a problem with being too cynical, skeptical? Sure. I also remain that a far more widespread problem is people who are firmly at the other end of the spectrum.

"At that event, Ken Fisher made a presentation that seems to be a mirror image of Gross’s misstep"

I don't know how people can listen to Fisher, who is so aggressively promotional, with those smarmy ads. Odd that I never see Fisher on financial media, it's always as banner ads on financial websites and the like.

As for Gross, I think the issue with Pimco is that you had two people who were the "face" of Pimco and El-Erian was always the far better public speaker. Yet, Gross was always interesting with his knowledge and experience. Now Gross is starting to seem to falter and there's no one that has been kind of groomed to be the next public face of Pimco (although I have said I thought Tony Crescenzi should be the next CNBC face of Pimco.)

I've stopped selling what I have left in Pimco funds, but would like to see a little clarity about the company getting its house in order before adding anything to Pimco offerings. Bill Gross comparing himself to Justin Bieber and Kim Kardashian is not exactly a confidence builder.

M*, Day 2: Bill Gross's two presentations Hi Professor David and MFOers,

With apologies to its author Elbert Hubbard, thank you for your Message to MFOers ( originally to Garcia). Your messages, in almost real time, of what’s what at the annual Morningstar Conference should permit us to take the investment initiative. So far that hasn’t happened. That’s not your fault. It’s like we are seated in the conference rooms with you.

It’s really not surprising that a fair review of the proceedings is almost always a mixed bag. Are the insights gleaned from the presentations worth the time and effort? Typically, these conferences generate a jumble of rubbish and a few gems. The wheat must be separated from the chaff.

For years (like 15), both my wife and I have been attending and even occasionally participating in the annual Las Vegas MoneyShow. Each year we question if the learning is worth the price. Yet each year we return with an optimistic mind-frame. Hope springs eternal. Fortunately we usually return home with a few nuggets of wisdom. So I suppose my answer is “yes”. Although the promises and expectations far exceed what is ultimately delivered, it is still a worthwhile time investment.

The Morningstar agenda at this conference is clearly directed at financial professionals. That suggests that the presentation bar should be set a bit higher given the likely sophistication of the audience.

Based on your summary reporting, the bar standard is unacceptably too low, or perhaps, the presentations are so generic or fuzzy, that the bar height can not even be accurately defined. That too is bad, but it is not a shock either. If the presenter actually had a special forecasting insight or investment preference, he/she is not likely to freely reveal it to a non-subscribing audience. If I were the presenter, I would reserve this gem for my paying clients.

I find it somewhat puzzling why a few MFO members are so short-tempered and even hostile towards Morningstar’s limitations, errors, and costs. Research and data collecting costs money. Folks are imperfect and blunders are made despite the best organizational, structural, and double-checking safeguards. Accepting that reality, I adopt a more forgiving posture. Even my Toyota was delivered with several minor flaws which the manufacturer quickly corrected.

I’m not advocating the elimination of skepticism. A skeptical attitude is needed when making all investment decisions. However, it has a limit to its usefulness. It has the usual diminishing returns characteristic. At some point, it detracts from permitting a timely decision from being made.

Morningstar is one of the preeminent mutual fund data sources available to us individual investors. Overall, it has served us well. How do I know this?

It has a growing legion of loyal customers who trust its services. It attracted a huge number of professionals at this session who were willing to invest time and to pony-up 795 dollars to attend these sessions. Its sponsor and exhibitor lists are impressive. It has a history that dates back to when Peter Lynch managed the Magellan fund. Morningstar must be doing something of service to the investing public.

Since it is a successful enterprise, it must be a win/win scenario for both the buyer and the seller. Otherwise money would not change hands. Morningstar is prosperous and expanding; it continuously tries to improve its products. Certainly not all of these experiments are successful or equally useful for its disparate customer base.

Early in its history, Morningstar was very weak on analytical talent. Originally they hired professionally trained writers while passing on market analytical/investment types. Eventually, Morningstar recognized that shortcoming and integrated Ibbotson into their team. As an elite provider of investment data and analyses, Morningstar is committed to keeping its edge. Sometimes their efforts work; sometimes these efforts fail. It is up to their users to assess the merits of these exploratory projects for their special circumstances.

It is far too easy to be a constant critic. The bad is overemphasized while the good is swept away without acknowledgment. If the Morningstar presentations are too dull or too inept, the answer is simple enough: abandon the ship.

As usual, Warren Buffett had a succinct and wise way of putting it: “ Should you find yourself in a chronically leaking boat, energy devoted to changing vessels is likely to be more productive than energy devoted to patching leaks.”

Regardless of its shortcomings, I plan to continue using Morningstar as a primary mutual fund data resource. In the end, it is my responsibility to critically examine that data to judge its reliability prior to making a decision.

Your description of Bill Gross’s weird behavior is reminiscent of a like event at the recent Las Vegas MoneyShow. At that event, Ken Fisher made a presentation that seems to be a mirror image of Gross’s misstep. It was totally not decipherable and made no sense whatsoever. To be generous, everybody has a bad day. Perhaps it was caused by the Chicago air compared to the Newport Beach air? Nope, these guys are just being human.

We are often Fooled by a Random Success. I capitalized the phrase because I coupled a Nassim Taleb saying with a contribution from an old friend. Even tossing 10 consecutive heads doesn’t mean we’re in control. Luck is always an investment component. For what it’s worth, we each have a 1 in 1024 probability of tossing 10 straight heads. Not likely, but doable.

Professor, please keep the report flow coming. I wish I were there with you.

Best Regards.

M*, Day 2: Bill Gross's two presentations Not all that long ago I considered Mr. Gross one of the brightest minds in the financial world. This story along with all the others that have floated out there does make me wonder what happened to him? He is 70 years old so it could be possible that a medical condition is evolving in him though I don't wish anything of the sort.

Perhaps it is time for him to enjoy life while he can.

M*, Day 1: Kunal Kapoor on Morningstar's devotion to investors @Maurice - In the FireFox Preferences, under 'Privacy':

• check the

Accept cookies from sites box.

• do

not check the

Accept third-party cookies box

• set

Keep until: to

ask me every time.

It's likely that you already have a long list of cookies with various settings, in your case probably mostly 'blocked'. Click on

Exceptions to see that list. You can now do one of two things: if you know what cookies that you would like to permit, you can comb through that list and change the settings. That can be a real pain, though, so it might be easier to just eliminate all of those cookie settings and start all over.

If you do that, with the settings as given above your browser should now automatically reject all of the third-party cookies, which are the advertising, tracking and other junk stuff that you really don't want.

Now each time you go to a new site you will of course be assaulted with a flurry of new cookie requests. Here's a suggestion on how to handle those:

First, accept cookies only from those sites that you want to allow. These may be either

Session Only or may have an expiration date, typically rather far in the future.

Second, you may visit sites that you want to take a look at, but not allow cookies if you can help it. The problem there is that many times some operational feature of a site will not function properly without those cookies. So here's a compromise that usually works-

• Allow at least one, typically the first one, for

Session Only* Deny all of the rest, especially any cookie that has an expiration date other than Session Only.

You will wind up with cookies on your browser, but hopefully only from sites that you have approved. If you frequently use your browser for checking bank balances, financial holdings, or other similar operations this is about the best compromise that I've been able to work out.

If you do inadvertently allow cookies that you want to delete, you can go back through the preferences to that list, and block them there.

Hope this helps a little.

OJ