On March 6, 2017, Morningstar announced their intention to displace 50 existing mutual funds from their $30 billion Morningstar Managed Portfolio program and replace them with nine brand-new Morningstar-branded funds. Understandably, there’s been a bit of interest in the financial media, though much of it is behind paywalls. (I’m not complaining, by the way. Journalists need to be compensated.) The most notable “free” articles are:

Advisers split on Morningstar’s new mutual funds

Morningstar makes bid to offer mutual funds for exclusive use of advisers

Like everyone else, Morningstar expands its advisory business

By far the most thorough and balanced piece was How and why Morningstar sliced 16 bps for RIAs by dumping third-party mutual funds and stamping its Switzerland brand on its own mutual funds, written by Janice Kirkel of RIABiz.

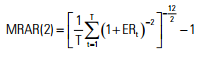

Predictably, much of the cover has been hasty and … hmmm, lightly-informed by reality. Some of the quoted advisors, for example, seem to have no idea that the Morningstar star ratings are not subjective judgments issued by Morningstar analysts. The star ratings are purely mechanical calculations. If the eventual Morningstar Core Equity fund receives a five-star (or one-star) rating, it will not be because Morningstar analysts like (or dislike), favor (or disfavor), approved of (or disapprove of) the fund. It will be a five- (or one-) star fund because when its performance statistics are plugged into this formula

they fall into the top 10% (or bottom 10%) of their peer group’s values. You may or may not be impressed with them, but Morningstar does not play favorites with them.

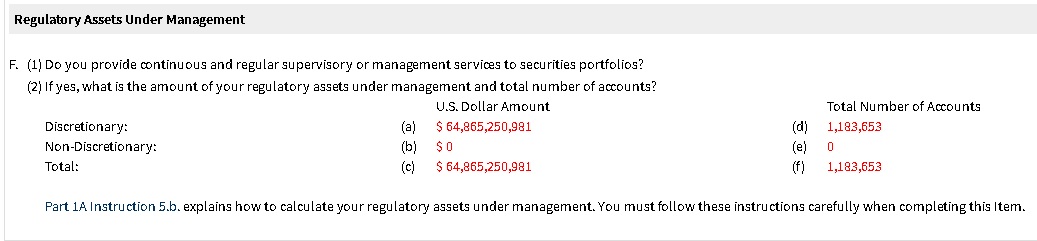

Similarly, few of them seem to understand that Morningstar is already in competition with them. A common refrain is “Once they join the fray and become a competitor to those they judge and report on, they’ve given up their objectivity.” Morningstar’s investment services already manage $66 billion in assets (Form ADV) for about 1.1 million accounts.

That’s grown from $2 billion in 2010 (old Form ADV). In addition, the Morningstar brand is on 21 ETFs and Morningstar employees have served as sub-advisers on mutual funds.

Here’s what we know

Morningstar has proposed launching nine funds. They are:

- Morningstar U.S. Equity Fund

- Morningstar International Equity Fund

- Morningstar Global Income Fund

- Morningstar Total Return Bond Fund

- Morningstar Municipal Bond Fund

- Morningstar Defensive Bond Fund

- Morningstar Multi-Sector Bond Fund

- Morningstar Unconstrained Allocation Fund

- Morningstar Alternatives Fund

Each fund will be a multi-manager operation. The half-blank prospectus leaves slots for three sub-advisors to each firm.

Morningstar proposes actively managing the allocation to each sub-advisor.

Morningstar will continue to use some third-party managers, so long as they’re willing to absorb a pay cut: “Given this, our continued conviction in a number of third-party managers that we use today, and our belief we can come to commercial terms with many of these managers, turnover should be moderate.”

The change may increase investors’ immediate-term tax liability, though Morningstar promises to try to mitigate it to the extent they can.

The funds will only be available through advisors to clients of the Morningstar Managed Portfolios program.

Not all of the Managed Portfolio programs will be affected. “Any portfolio that uses active funds would be affected. Those portfolios include our Mutual Fund and Active/Passive Asset Allocation, Retirement Income, Multi-Asset Income, and Absolute Return Portfolios. In these cases, where relevant, we’d replace third-party active funds with the appropriate Morningstar funds. Other portfolios will not be affected, such as the ETF Asset Allocation Portfolios, which invest only in ETFs, and the Select Equity Portfolios, which invest directly in stocks and other securities.”

The funds will launch in the fourth quarter of 2017.

Here’s what we do not know

There is no hint about who the sub-advisors will be. Morningstar’s filings do allow that some of their advisors may have no experience in managing mutual fund portfolios: “Morningstar funds will give us access to managers who, while skilled and capable, don’t offer mutual funds and will allow us to implement investment ideas from our valuation-driven, contrarian-minded investment approach that the third-party fund structure would not.” And again, the new family “gives us access to asset managers who do not offer mutual funds.”

There is no word about what the fund expenses will be. Morningstar’s argument is that they will drive expenses down by paying the new sub-advisors less than they currently pay the outside fund managers. It would be attractive to Morningstar if they reduce what they pay by 50%, reduce what they charge by 20% and pocket the difference.

As an outsider, I do not have access to data that demonstrates Morningstar’s track record as an asset manager. The folks at Morningstar note, “All Morningstar Managed Portfolios are measured and reported against stated benchmarks, with most of these strategies published in the U.S. Separate Accounts (SA) database in Morningstar Direct.” They are certainly under no obligation to disclose that information to anyone except their investors and the appropriate regulators. Morningstar has attracted billions in AUM but, to be honest, so have a bunch of painfully mediocre firms.

Three things we do not know, but which might be true

-

Morningstar analysts would ridicule anyone else pulling this move. As you might imagine, this claim is the subject of a vigorous exchange of views between us and the folks at Morningstar. At the crux is the question of whether Morningstar’s analysts think you should invest be willing to invest in managers who have less than a couple billion in assets in a fund and four years of a public track record managing it. We’re looking at the same data but placing a different interpretation on it. It feels like a classic glass half full / glass half empty discussion.

The glass might be half full. Our colleagues in Chicago note that they do cover a number of exemplary, smaller and/or newer funds. Nadine Youssef, Morningstar’s director of media relations, shared some of the data: “As of today, Morningstar has assigned a Morningstar Analyst Rating™ of Gold, Silver, or Bronze to 593 unique non-allocation funds. Of those, 16 were incepted in the past five years, 160 of these funds had less than $2 billion in assets under management (AUM), and 13 of these funds were incepted in the past five years and had less than $2 billion in AUM. We are happy to share additional examples of recommending smaller, lesser-known funds.” Jeff Ptak added a reminder about the Morningstar Prospects list, which highlights promising funds (I’ve been able to find four funds added last year, but that’s about what I know) and is available to advisers.

The glass might be half-empty. Receiving Morningstar analyst coverage is an important, perhaps critical, source of validation for many funds. It marks the point where Morningstar deems them as “relevant.” For many small funds, no degree of distinctiveness or accomplishment seems likely to earn them the “relevance” necessary.

Universe: 5-star funds

# of funds

# of funds with analyst coverage

Chance of coverage

Under a billion

350

18

6.0%

$1-2 billion

78

17

21.8

2-3 billion

38

14

36.8

3-4

34

14

41.2

4-5

21

11

52.4

Over $5 billion

120

100

83.3

(five star, distinct portfolio, not life-cycle, assets at or below target amount, as of 4/1/17)

It appears that $4 billion is the breakeven point, where a five-star fund earns a 50/50 chance of coverage. But even the best funds under $4 billion still have a fraction of the coverage of average funds over $4 billion.

# of funds

# of funds with analyst coverage

Chance of coverage

All funds over $5 billion

472

369

78.2%

Funds below $4 billion with 5-star rating overall, plus 4- or 5- star rating for the past 3-, 5- and 10-year periods

238

40

16.8

Greater likelihood of any fund over $5 billion getting analyst coverage compared to the most consistently excellent funds under $4 billion is 4.6x.

About the same appears to be true if you look at probabilities by age. There are 66 five-star funds which have been around for less than four years; of those, five have analyst coverage. 44 funds have been around for more than four, but less than five years. Of those, two have analyst coverage. So, 6% of five-star funds receive analyst coverage by their fifth anniversary.

Senior folks on the research end (Mr. Rekenthaler, quite clearly) are increasingly skeptical of the prospects for active management and of trendy fund categories like liquid alts, non-traditional bonds, and so on.

-

Morningstar may not have the freedom to care about damage to the traditional brand. To be blunt, their old fund-ratings core is somewhere between stagnant and declining. While some of the older employees doubtless have a soft spot for star ratings and monthly fund ratings packets that snap into three-ring binders, that’s not the future. The serious money comes from managing money, and a firm with $600 million in expenses is built to pursue serious money.

-

Morningstar will reward managers who stick to their knitting. Morningstar finds two faults in the funds they’ve been using: they charge too much and they’re too unpredictable. That is, the managers don’t stick closely-enough to their benchmarks. Here’s Morningstar’s explanation of why they want to contract directly with managers for narrow portfolios.

The Morningstar funds should afford our portfolio managers greater flexibility to express investment ideas and adjust positions as circumstances warrant. Currently, it can be a bit cumbersome to adjust allocations to third-party mutual funds. That process should be smoother with Morningstar funds, which will invest through separate-account sleeves. We believe we will be able to reallocate capital between subadvisors more nimbly and precisely than before in this format.

The implied problem is that independent managers don’t always color inside the lines: a large cap manager might choose to hold a lot of cash, a small cap manager might hold some mid-cap stocks, or the domestic bond fund manager might pick up some Euro-denominated debt. That’s good for their investors because they’re actively pursuing the portfolio with the best risk-reward profile, style box be damned. It’s bad for Morningstar’s managers-of-managers: suddenly a portfolio of funds that targets 5% cash might be at 10% cash because of the not-immediately-disclosed decisions of their managers. That problem is mitigated if your small cap value guy is, like an index, always 100% invested and only invested in securities representative of the benchmark index.

That propagates up the chain: the “large-cap growth” manager within the U.S. Core Equity fund needs to be always and only large-cap growth and the U.S. Core Equity Funds needs to be always and only U.S. core equity so that the managers at the level above them have very predictable pieces from which to assemble a portfolio.

Bottom line: One of Morningstar’s core values is “Investors first.” The question is “which investors?” As a publicly-traded corporation, the answer has to start with “investors in Morningstar (MORN).” Professor Stephen Bainbridge of the UCLA School of Law wrote, “the law requires corporate directors and managers to pursue long-term, sustainable shareholder wealth maximization in preference to the interests of other stakeholders or society at large” (A Duty to Shareholder Value, New York Times, 04/16/2015). Discharging that responsibility likely entails upholding the Morningstar brand identity but that’s necessarily secondary. Mr. Kapoor and his team have a primary responsibility to make Morningstar shareholders richer, both by attracting assets (financial and human) and extracting the greatest possible return from them.

Potential investors might ponder the implicit advice from the Morningstar research teams: don’t get sucked in by the siren song on smooth marketers and untested teams, hold off writing a check, put these funds on your watchlist for 2022 – 2025, come back then and see whether the alluring idea proved itself in the marketplace.

Morningstar has at least three SEC filings that interested parties might want to pursue. The most informative is their discussion for investors and attendant FAQ. The next-best is their fund prospectuses, which still lack the most vital information (expenses and managers, for instance). The least helpful is their request for exemptive relief which, at base, just gives them permission to have a bunch of sub-advised funds.