Morningstar held its annual investment conference in its headquartered city of Chicago last week. That’s a couple months earlier than typical, perhaps to give it some distance from September’s ETF conference. Pink and purple tulips lined Michigan Avenue and Millennial Park. April showers abounded. The Intelligentsia coffee bar at 53 West Jackson Blvd each morning never smelled better.

In the opening keynote, Morningstar’s 42 year old CEO Kunal Kapoor, a 20-year veteran of the firm and graduate from University of Chicago, stated “It’s never been a better time to be an investor …”

He was alluding to the diversity of investment products, migration to lower fees, and proliferation of financial technology tools. Indeed, he highlighted the recent acquisition of Pitchbook, which expands Morningstar’s financial database to the ever growing private equity sector, improved fixed income statistics, as well as the new “Best Interest Scorecard,” which helps quantify and document portfolio construction in anticipation of DOL’s Conflict of Interest Rule.

In a later session, entitled “Industry Disruption,” Reformed Broker Josh Brown quipped: “Not to dampen the mood here, but I don’t think it’s the best time for investors … It’s the best time for people in this room, perhaps, the financial advisors, but not the investors.”

Attendance this year: 2,197, including 1,313 registered attendees (mostly advisors), 756 exhibitors, 175 exhibitor booths, and 45 speakers.

When Josh made his comment, he might just as well have stated “It’s the best time to be Morningstar…” Its sales and display booths occupied the entire center section of the vast exhibit hall at McCormick Place.

Morningstar’s stated mission is to create great products that help investors reach their financial goals, but its portfolio of products is directed at advisors, asset managers, retirement plan providers and sponsors, private equity and institutional investors, and finally individual investors. As described here, its goal is to “Widen our economic moat, increase our intrinsic value,” making money through licenses and subscriptions, asset-based fees, and transaction-based fees. As David reported last month, Morningstar has filed for nine self-branded mutual funds.

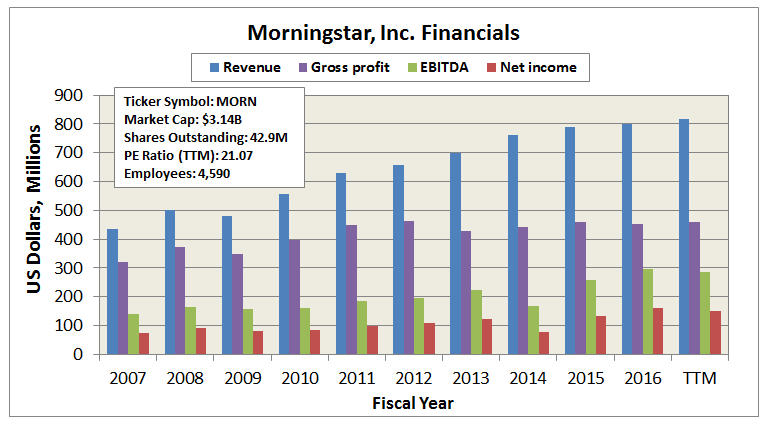

The company incorporated in 1984 and started trading publicly in 2005. Since going public, MORN has returned 11.9% annually versus 8.3% for S&P500, but it’s trailed the market by 27% during the last one and three year periods and 44% over the last five years; in fact, it still trades below its 2007 peak.

Its founder and chairman, Joe Mansueto, retains 24.0 million shares, or 56%, currently valued at $1.8 billion. While his annual salary is a nominal $105,000, he was gifted 182,668 shares in December 2016, or $13 million, and similar amounts in 2015, 2014, and 2013. Morningstar also pays a 1.25% dividend, which earns him another $22 million annually.

During the same session, Josh railed on how many “bad choices” are available to investors. Given “way too many choices” these days, he often sees his role as a “client’s bouncer.”

Answering why the financial industry is not very well regarded by the public, Morningstar’s Don Philips lamented that the industry does tend to make things more complex than it needs to be. The irony, of course, is that the more complex investing appears, the more the need for financial advisors and thus for Morningstar to help point the way. “Fintech was supposed to be the answer” to address the popularity issue. Today, only 50% of those eligible invest their retirement plans. He adds: “Our community serves rich white males very well.”

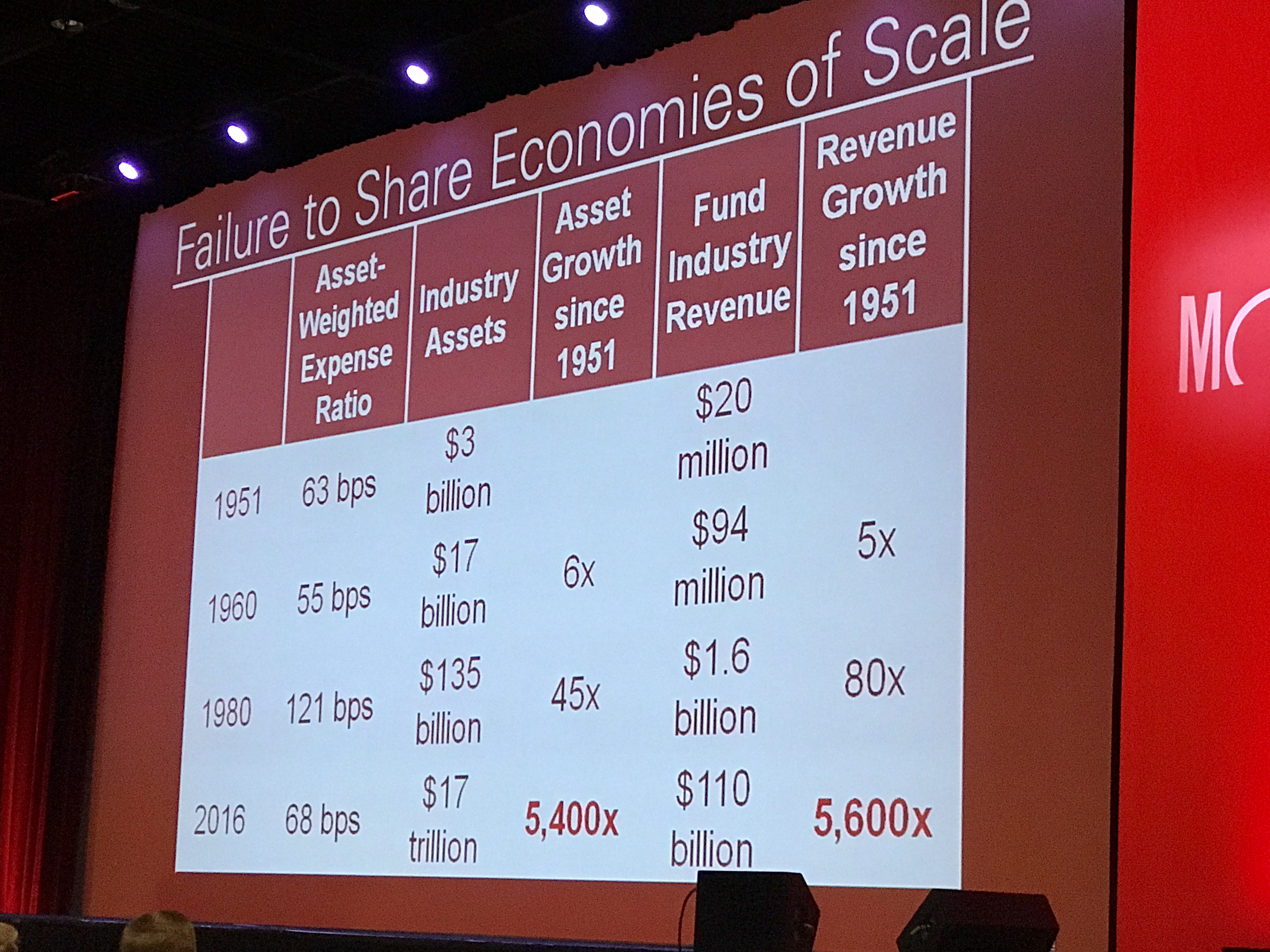

Vanguard’s founder and inventor of the first index fund, John Bogle, presented a video highlighting how the industry has failed to share economies of scale. Basically, he shows mutual fund industry revenue growing 5600 fold (14% per year!) since 1951, but on aggregate assets held, investors pay a comparable level of fees.

Bogle is particularly skeptical of publicly traded mutual fund houses, as John Rekenthaler reports, and of the asset-based fee model for financial advisors. Mr. Bogle believes, advisors should be paid hourly like accountants and lawyers.

And what about reducing the complexity of investing? During his question and answer session, he reiterated his belief that a simple balance portfolio, somewhere between 50/50% and 70/30% stocks/bonds, represents a perfectly satisfactory approach for most investors.

Lunchtime keynote speaker, best-selling author Michael Lewis, believes the cause of poor behavior often lies in the incentive structure, as detailed in Flash Boys and The Big Short. For example, if bonuses are based on amount of assets under management, then fund houses will encourage employees to accumulate assets. He shared that he renegotiated his own contract to eliminate the traditional book advance, opting instead to take a greater direct stake in a book’s success or failure. “It makes me a better writer.”

(His insight here reminded me of Noam Chomsky’s recent documentary, entitled “Requiem for the American Dream.”)

As for his next book? He’s hoping it will not be about finances, since that would mean something else has gone very wrong, yet again. He seemed to tip his hand that it could be about the recent election, more specifically, the unprecedented hand-off, or lack of hand-off, with the incoming Trump administration. He described how the Obama administration had followed the George W. Bush administration’s model in preparing incoming briefings for the transition teams, only with the Trump team “nobody showed up.” He cautions that the lack of experienced leadership tasked with running the enormously complex federal government has never been greater.

Mr. Lewis spent many hours getting to know the office of the president, as depicted in Vanity Fair’s article Obama’s Way. He lamented about not yet publishing the material he has gathered on How To Be President. (“You have one hour to live,” he prodded the former president, “tell me what I need to know to do this job …”) He envisions a short book or manual. “Not that Trump would read it,” Mr. Lewis acknowledged, “but maybe someone would read it to him, like someone from Fox News.”

Morningstar’s Paul Ellenbogen demonstrated the “Best Interest Scorecard,” which should be released soon on Morningstar Direct and Morningstar Office. It incorporates past performance, fund quality, fees, risk tolerance, and investment timeline. For fund quality, the tool relies on Morningstar’s qualitative medal system. For those funds not covered by Morningstar analysts (most funds actually), they have developed a so-called quantitative quality rating, trying to assess characteristics like process, people and parent from collected databases.

Morningstar’s behavioral economist Sarah Newcomb shared her recent study, entitled When More Is Less – Rethinking Financial Health. Her conclusions:

- Time is money – The further ahead a person thinks in time and the clearer their picture of the future, the better their behavior in terms of cash, credit, and savings management.

- Power is happiness – Across all income levels, people who believe they create their own financial destiny experience, on average, have more positive emotions with respect to money than their peers who believe they do not have power in their financial lives.

In the session entitled “Straight Talk About Strategic Beta,” two of the most thoughtful fund managers today, Wes Gray of Alpha Architect and Patrick O’Shaughnessy of O’Shaughnessy Asset Management, reinforced their shared belief in evidence-based investing.

“Gather data and find what has historically worked, with some predictive power,” says Patrick. His book Millennial Money – How Young Investors Can Build A Fortune advocates investing in quality global stocks, starting at youngest age possible and throughout your lifetime. He, like Meb Faber, recently launched a well received podcast series, entitled “Invest with the Best,” which can be followed at his website The Investor’s Field Guide.

Wes warns that funds often try to reap benefits of academic research by putting factors, like value, in title. “You gotta look at what it’s called versus what it does.” He explains that most fund managers want to gather assets, so they build portfolios like “value light,” otherwise folks get scared out. Unfortunately, such funds are little more than closet indexers with a higher expense ratio.

His new Active Share Visualizer helps point the spotlight on closet indexers. He added a couple of other warnings: 1) I’ve never seen a bad backtest, and 2) it has to hurt to pay off. His fourth and latest book is Quantitative Momentum: A Practitioner’s Guide to Building a Momentum-Based Stock Selection System.

Bottom-line: Both Patrick and Wes believe that quantitative and systematic rules-based investing is better than ad-hoc.

Finally, in the session called “Absolute Return Funds: Absolute Fabulous or Absolute Rubbish,” Marta Norton, of Morningstar’s managed portfolio group, made the only sense on the panel when describing how her fund gets built: “Start with maximum drawdown acceptable and let everything else fall out.” In her case, the MAXDD is -12%, which then translates to an expected return of cash plus 2 – 3%, and an equity beta of 0.3 or less.

I walked out of the conference after this last session with a few misgivings. Despite being highly impressed with Marta, it felt a little awkward to have a Morningstar moderator interviewing a Morningstar fund manager along with managers from competing fund houses. Such situations conceivably create the appearance of conflict of interest.

In other words and in all things, Morningstar should heed the lesson of Caesar’s wife … to be above the suspicion of impropriety.

Here’s a link to Morningstar’s coverage of the conference.