Dear friends,

Spring is a time when we celebrate the small and uncertain signs of hope. Weighed down by the exhaustion of war and politics, pandemic and winter, we look happily at the first crocus to spring which shoulders its way through the autumnal leaf mold. We’re reluctant to invest too much in it, knowing that winter has not yet suffered its final defeat. (Here, anyway. Last Wednesday’s upper 60s was followed by Thursday’s measurable snow.)

And still, it’s in our nature to hope. That’s what makes the prospect of tomorrow bearable. And so I hope that the 1.7 million new jobs created so far this year, and the fall in unemployment to 3.6%, is a signal of sustainable economic vitality.

I hope that the Ukrainian people prevail quickly. Their fortitude in the face of heartbreaking losses heartens many. The suffering now is immense and the rebuilding will consume decades, but that’s an argument to act rather than to despair. Consider donating, as we’ve done on several occasions in the past month, to the UN Commission for Refugees or one of the groups vetted by Charity Navigator. There are small children who will remember the conflict for the rest of their lives; I’m hopeful that they have cause to remember the unstinting kindness of strangers as well.

I hope that the Ukrainian people prevail quickly. Their fortitude in the face of heartbreaking losses heartens many. The suffering now is immense and the rebuilding will consume decades, but that’s an argument to act rather than to despair. Consider donating, as we’ve done on several occasions in the past month, to the UN Commission for Refugees or one of the groups vetted by Charity Navigator. There are small children who will remember the conflict for the rest of their lives; I’m hopeful that they have cause to remember the unstinting kindness of strangers as well.

In this issue …

My colleagues engage in a sort of wide-ranging conversation while inviting you along.

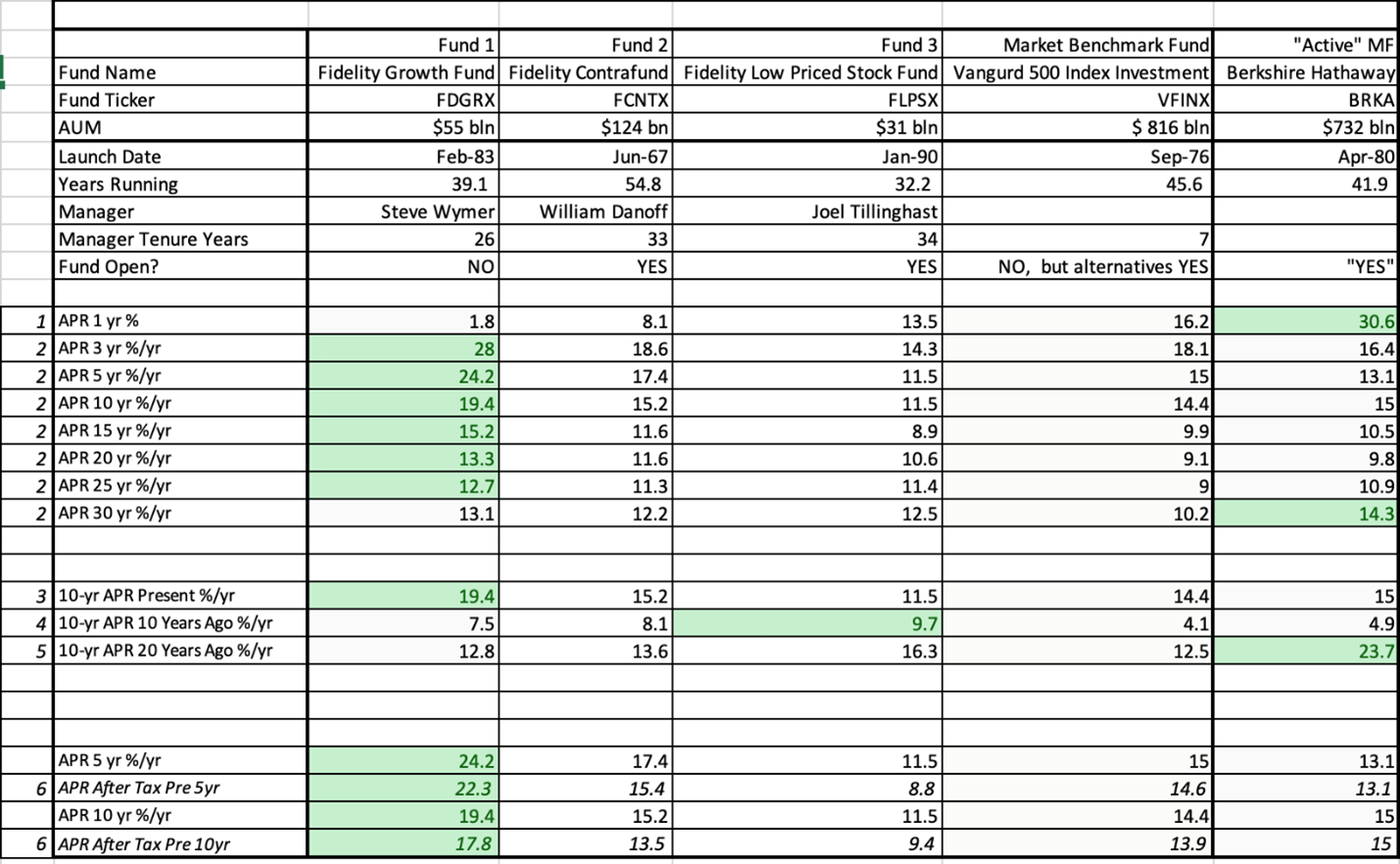

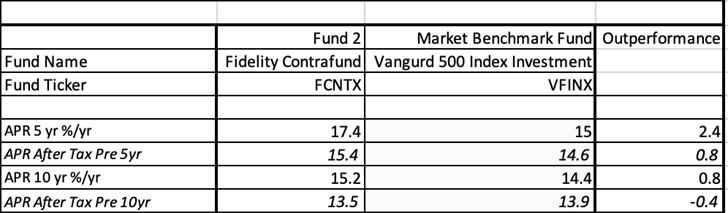

Devesh Shah takes a long look at Peter Lynch’s claim that Fidelity’s active funds crush their passive counterparts. I suspect Devesh’s response might be fairly summarized as, “not so much, really. And you certainly can’t count on it continuing.” Devesh’s own portfolio, he notes, holds nary an active fund, though he allows that he’s still examining the evidence.

Mark Freeland weighs in with a long and careful piece about what indexes – the driver of index funds – actually are, and aren’t, and how they come to be.

David Snowball shares his side of the conversation, walking through his take on the limits of passive investing and a strategy for constructing a more actively managed portfolio that gets you where you want to go.

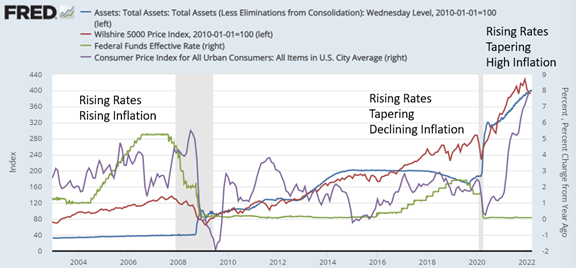

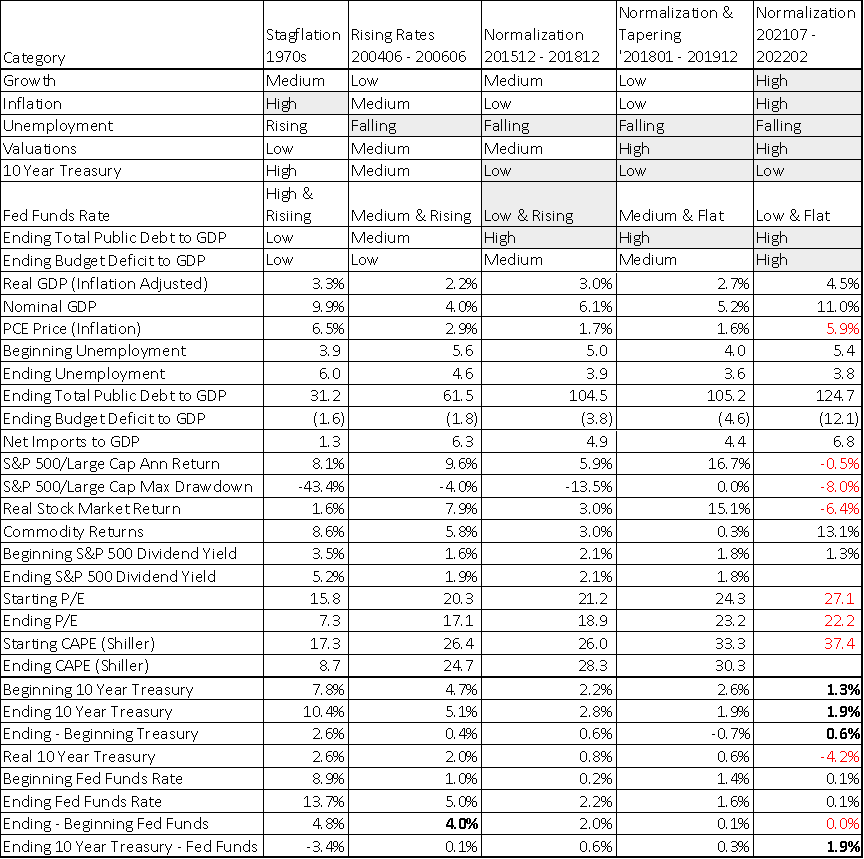

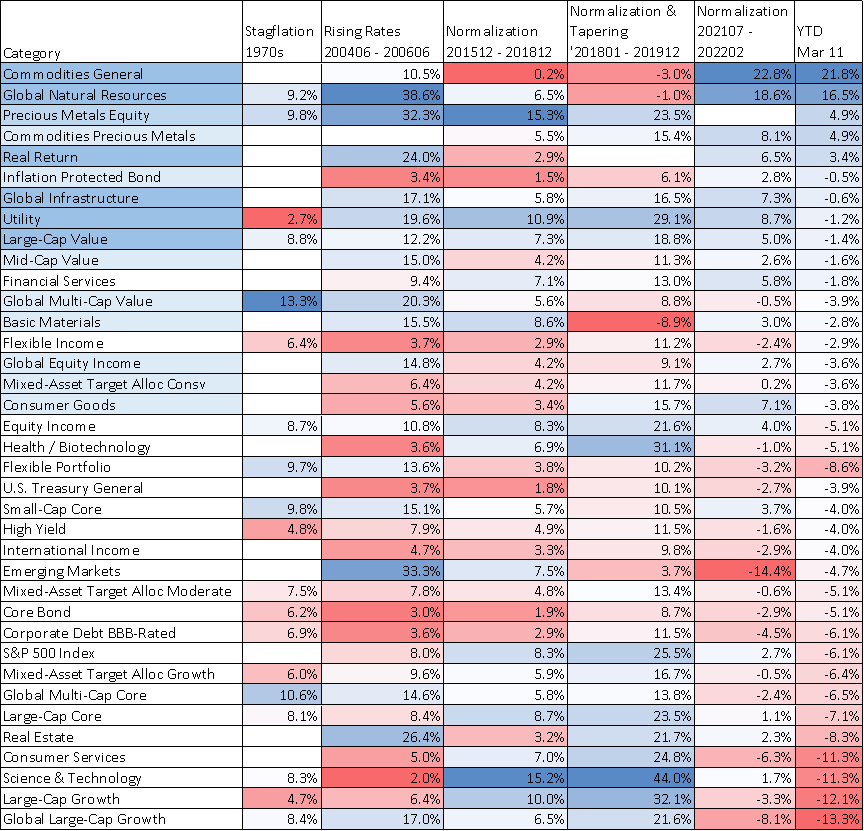

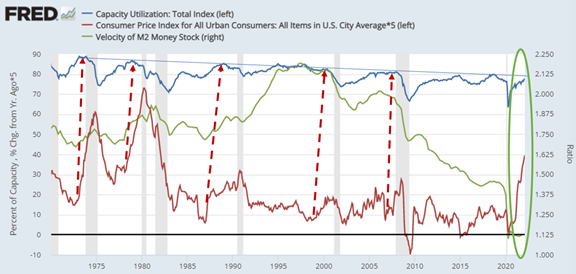

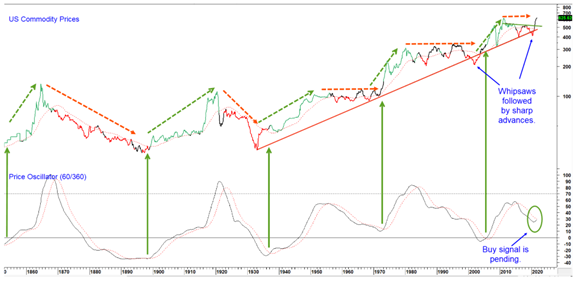

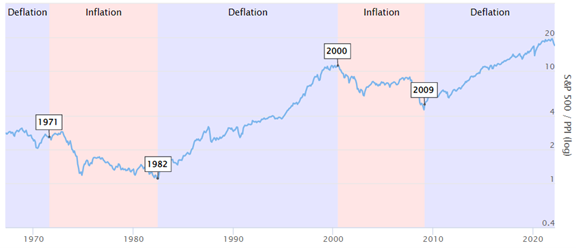

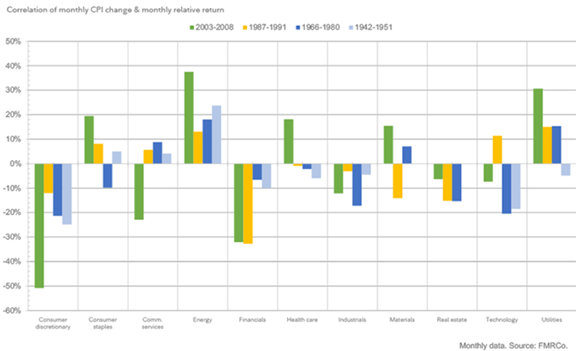

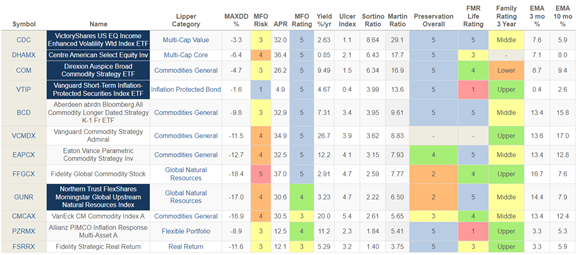

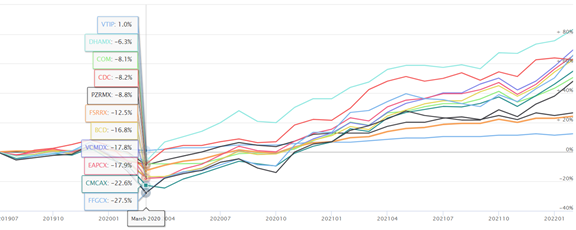

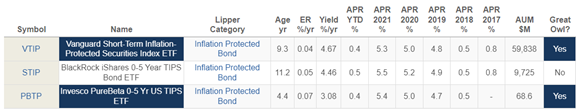

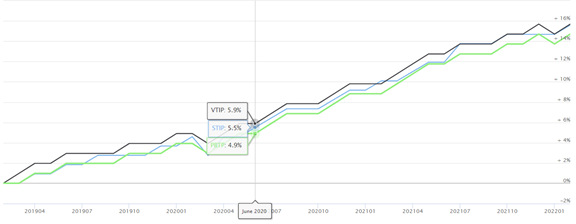

Lynn Bolin offers a really solid analysis of which resources are best buffered against the effects of inflation (or, indeed, capable of profiting from it) and highlights the sectors and funds to favor when investing in the face of inflation.

Charles Boccadoro takes on the conventional wisdom: high inflation means high-interest rates means long-term bond funds crash means … run away!!! While recognizing the challenge, he offers reason to have a bit more faith in the long-term funds.

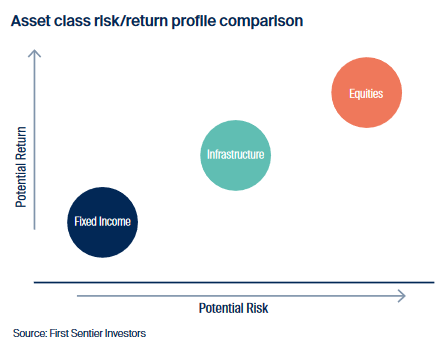

Speaking of inflation, we share an Elevator Talk with Jessica Jouning, one of the managers of the First Sentier American Listed Infrastructure fund. “Infrastructure” is all that stuff that makes our version of civilization possible: power grids, cell towers, solar farms, roads, railroads, waste treatment plants, and all. Some infrastructure is the responsibility of governments, some is funded by private investors, and others by corporations listed on US exchanges. First Sentier invests in the latter and seems to be the only infrastructure fund that targets only resources in the US.

The Shadow catches us up with the comings and goings in the fund industry, including one instructive fund liquidation, small wins, and new funds.

We hope you enjoy it and connect with the folks who produce it for you. We’re all linked in the articles we write!

Two thumbs up

Thumbs up: There are 2600 taxable bond and allocation funds. Only 75 of them are above water as of March 30, 2022. Those include four of the five CrossingBridge and RiverPark funds advised or sub-advised by David Sherman and the team at Cohanzick, as well as their Pre-Merger SPAC ETF. Their remaining fund, Responsible Credit, is down just 0.3% which places it in the top 3% of its peer group. With 84% of its funds and ETFs in the black, no other sponsor is close.

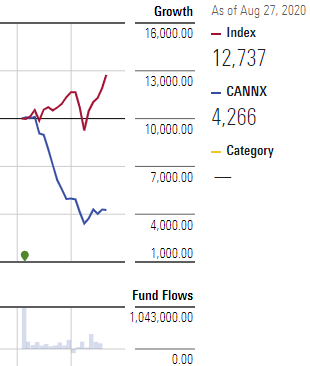

Thumbs up: Morningstar just downgraded Cathie Wood’s ARK Innovation ETF to an analyst rating of “negative.” The fund is down 58% since its peak in February 2021. Morningstar astutely notes that there are “few signs of improving its risk management or ability to successfully navigate the challenging territory it explores” (Robby Greengold, 3/29/2022). Good call, guys! Even before its epic collapse, Mr. Greengold warned that “its lone portfolio manager, inexperienced team, and lax risk controls make it ill-prepared to grapple with a major plot twist” (3/30/2021). MFO issued similar warnings while most of the financial media fawned over Ms. Woods’ genius, posting daily expositions of her latest moves. That should serve as both a warning (of the value of relying on unvetted sources whose qualifications come down to publishing a blog with a dramatic name) and a celebration (of people who have some principle greater than “more clicks”).

In Memoriam

We note, with sadness, the passing of two monumental figures.

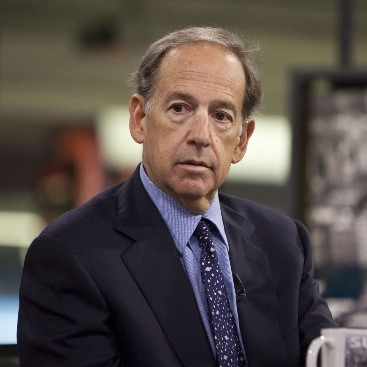

Photo: Brian Snyder of Reuters

Edward “Ned” Johnson III (1930-2022) died on March 23, 2022. Mr. Johnson was CEO of Fidelity Investments, a firm started by his father Edward (1947) and now led by his daughter Abigail, for 37 years. He also managed Fidelity Magellan before surrendering those responsibilities in 1977 to some guy named Lynch.

Fidelity was started as a sort of glorified family office to manage the family’s considerable investments. (The Johnsons have been in Boston since 1635 and made a fortune in the department store business.) Ned utterly transformed the firm, driving it into prominence in the 1960s with aggressive stock funds, and in the 1970s and 80s with star manager funds. At the same time, he was an early champion of money market mutual funds to offer investors better-than-bank returns with effectively no downside risk. During his tenure as CEO (1977-2014), Fidelity’s assets grew from $4 billion to $7 trillion. (Put more starkly, from four billion to seven thousand billion.) At his death, Fidelity had nearly $12 trillion in assets under management and his family owned half of the spectacularly profitable business. He was, very quietly, a champion of the arts and an incredibly generous philanthropist.

Mr. Johnson is survived by his wife of 62 years, three children, seven grandchildren, and several million shareholders.

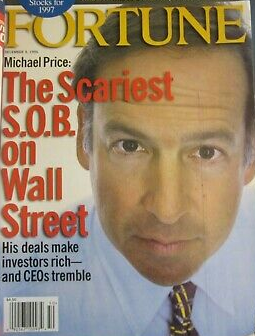

Michael F. Price (1951-2022) died on March 14 after a lengthy illness. As an investor, Mr. Price was the antithesis of Ned Johnson. Mr. Johnson’s family was fabulously wealthy; Mr. Price’s ran a clothing shop. Mr. Johnson’s mantra was something like “go (or go-go) for the growth.” Mr. Price sought profit elsewhere, by investing in distressed businesses whose management might be pressured to unlock the value that was already present. He explained that “Max taught me that if you really wanted to find value, you had to dig through stuff no one else wanted to look at.” Seth Klarman, himself a famous value investor and founder of the Baupost Growth hedge fund, observed that watching Price taught him that “the more obscure and murky the security sounds, the higher the chance it will be interesting.” Mr. Price’s most famous coup was forcing Chase Manhattan Bank to “sell divisions or take other actions” to raise the stock price; with the firm’s purchase by Chemical Bank, Price’s investors realized a 70% return.

Michael F. Price (1951-2022) died on March 14 after a lengthy illness. As an investor, Mr. Price was the antithesis of Ned Johnson. Mr. Johnson’s family was fabulously wealthy; Mr. Price’s ran a clothing shop. Mr. Johnson’s mantra was something like “go (or go-go) for the growth.” Mr. Price sought profit elsewhere, by investing in distressed businesses whose management might be pressured to unlock the value that was already present. He explained that “Max taught me that if you really wanted to find value, you had to dig through stuff no one else wanted to look at.” Seth Klarman, himself a famous value investor and founder of the Baupost Growth hedge fund, observed that watching Price taught him that “the more obscure and murky the security sounds, the higher the chance it will be interesting.” Mr. Price’s most famous coup was forcing Chase Manhattan Bank to “sell divisions or take other actions” to raise the stock price; with the firm’s purchase by Chemical Bank, Price’s investors realized a 70% return.

In 1974, he accepted a job as a research assistant to Max Heine, of Heine Securities. He and Mr. Heine managed three value funds, the Mutual Series, and did so brilliantly. Together they tended to end up on lists with the likes of Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch, T. Rowe Price (the guy, not the company), John Templeton, and Benjamin Graham. In 1982, he became a full partner and, in 1988, with Mr. Heine’s passing, bought the firm and became the president and chairman. He grew the firm’s assets from $600 million to $16 billion and, in 1996, he sold the Mutual Series to Franklin Templeton Investments. He stepped down as manager two years later. In 2001, five years after the sale, he left entirely and launched his own company, MFP Partners, LP.

Inherent in his investment style was the need to confront recalcitrant corporate leaders on behalf of their shareholders. In disrupting the clubby world of corporate leadership, he was awarded the sobriquet “the scariest SOB on Wall Street” (Fortune cover, 12/1996).

Inherent in his investment style was the need to confront recalcitrant corporate leaders on behalf of their shareholders. In disrupting the clubby world of corporate leadership, he was awarded the sobriquet “the scariest SOB on Wall Street” (Fortune cover, 12/1996).

Hedda Nadler, president of Mount & Nadler which provides public relations for financial services firms, knew Mr. Price for decades and disagrees with the label.

We had the privilege of being PR counsel to Mutual Series Funds, working with Max Heine and Michael Price since 1980. That relationship continued until 1996 when Michael sold to Franklin Templeton.

Michael was always loyal and caring about the people around him, including us. He was especially devoted to his mentor Max and had a big portrait of him hanging in his office.

We continued to have lunch together every several months which was only interrupted by the pandemic. He’d regale me with stories about undervalued stocks he found and Mutual Series alums.

While a Fortune cover called him ‘the meanest SOB on Wall Street’, the Michael we knew was kind, generous, and a mensch. He was low key, a devoted family man, and very loyal.

The world is a lesser place without Michael.

Price was married and has four children.

Thanks, as ever …

To Charles, Devesh, Mark, Lynn, and Bill, who are doing some really remarkable work for MFO. Reach out to them if something they’ve written strikes you and let them know.

To Charles, Devesh, Mark, Lynn, and Bill, who are doing some really remarkable work for MFO. Reach out to them if something they’ve written strikes you and let them know.

Thanks especially to The Few, The Proud, The Regulars: Greg, William, another William, Brian, David, Wilson (thank you, sir!), and Doug. And we’d never forget our new contributors, Jonathan, Joseph, and Trev.

Wishing you all a joyful month, and looking forward to celebrating our 11th anniversary with you in May,