This is an update of our profile from September 2011. The original profile is still available.

Objective

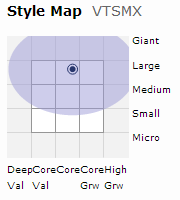

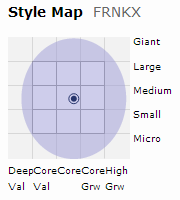

The Fund pursues long-term capital appreciation by investing primarily in common stocks of small and mid-cap companies, those with market caps under $5 billion. The Fund typically invests in 40 to 50 companies. The manager reserves the right to go to cash as a temporary move but is generally 94-97% invested.

Adviser

Walthausen & Co., LLC, which is an employee-owned investment adviser located in Clifton Park, NY. Mr. Walthausen founded the firm in 2007. In September 2007, he was joined by the entire investment team that had worked previously with him at Paradigm Capital Management, including an assistant portfolio manager, two analysts and head trader. Subsequently this group was joined by Mark Hodge, as Chief Compliance Officer, bringing the total number of partners to six. It specializes in small- and mid-cap value investing through separate and institutional accounts, and its two mutual funds. They have about $1.4 billion in assets under management.

Manager

John B. Walthausen. Mr. Walthausen is the president of the Advisor and has managed the fund since its inception. Mr. Walthausen joined Paradigm Capital Management on its founding in 1994 and was the lead manager of the Paradigm Value Fund (PVFAX) from January 2003 until July 2007. He oversaw approximately $1.3 billion in assets. He’s got about 35 years of experience and is supported by four analysts. He’s a graduate of Kenyon College (a very fine liberal arts college in Ohio), the City College of New York (where he earned an architecture degree) and New York University (M.B.A. in finance).

Strategy capacity and closure

In the neighborhood of $2 billion. That number is generated by three constraints: he wants to own 40 stocks, he does not want to own more than 5% of the stock issued by any company, and he wants to invest in companies with market caps in the $500 million – $5 billion range. In the hypothetical instance that market conditions led him to invest mostly in $1 billion stocks, the calculation is $50 million invested in each of 40 stocks = $2 billion. Right now the strategy holds about $200 million.

Active share

Not calculated. “Active share” measures the degree to which a fund’s portfolio differs from the holdings of its benchmark portfolio. High active share indicates management which is providing a portfolio that is substantially different from, and independent of, the index. An active share of zero indicates perfect overlap with the index, 100 indicates perfect independence. They’ve done the calculation for an investor in their separate accounts but haven’t seen demand for it with the mutual funds.

Management’s stake in the fund

Mr. Walthausen has between $500,000 and $1,000,000 in this fund, over $1 million invested in his flagship fund, and he also owns a majority stake in the fund’s adviser.

Opening date

December 27 2010.

Minimum investment

$2,500 for all accounts. There’s also an institutional share class with a $100,000 minimum and 1.22% expense ratio.

Expense ratio

1.47% on an asset base of about $40 million (as of 03/31/2014).

Comments

It’s hard to know whether to be surprised by Walthausen Select Value’s excellent performance. On the one hand, the fund has some fairly pedestrian elements. It invests primarily in small- to mid-cap domestic stocks. Together they represent more than 90% of the portfolio, which is about average for a small-blend fund. Likewise for the average market cap. The portfolio is compact – about 40 names – but not dramatically so. Their strategy is to pursue two sorts of investments:

Special situations (firms emerging from bankruptcy or recently spun-off from larger corporations), which average about 20% of the portfolio though there’s no set allocation to such stocks.

Good dull plodders – about 80% of the portfolio. These are solid businesses with good management teams that know how to add value. This second category seems widely pursued by other funds under a variety of monikers, mid-cap blue chips and steady compounders among them.

His top holdings are shared with 350-700 other funds.

And yet, the portfolio has produced top-tier results. Over the past three years, the fund’s 17.8% annualized returns places it in the top 3% of all small-blend funds. It has finished in the top half of its peer group each year. It has never trailed its peer group for more than two consecutive months.

Should we be surprised? Not really. He’s doing here what he’s been doing for decades. The case for Walthausen Select Value is Paradigm Value (PVFAX), Paradigm Select (PFSLX) and Walthausen Small Cap Value (WSCVX). Those three funds had two things in common: each holds a mix of small and mid-cap stocks and each has substantially outperformed its peers.

Paradigm Select turned $10,000 invested at inception into $16,000 at his departure. His average mid-blend peer would have returned $13,800.

Paradigm Value turned $10,000 invested at inception to $32,000 at his departure. His average small-blend peer would have returned $21,400. From inception until his departure, PVFAX earned 28.8% annually while its benchmark index (Russell 2000 Value) returned 18.9%.

Walthausen Small Cap Value turned $10,000 invested at inception to $26,500 (as of 03/28/2014). His average small-value peer would have returned $17,200. Since inception, WSCVX has out-performed every Morningstar Gold-rated fund in the small-value and small-blend groups. Every one. Want the list? Sure:

- Artisan Small Cap Value

- DFA US Microcap

- DFA US Small Cap

- DFA US Small Cap Value

- DFA US Targeted Value

- Diamond Hill Small Cap

- Fidelity Small Cap Discovery

- Royce Special Equity

- Vanguard Small Cap Index, and

- Vanguard Tax-Managed Small Cap

The most intriguing part? Since inception (through March 2014), Select Value has outperformed the stellar Small Cap Value.

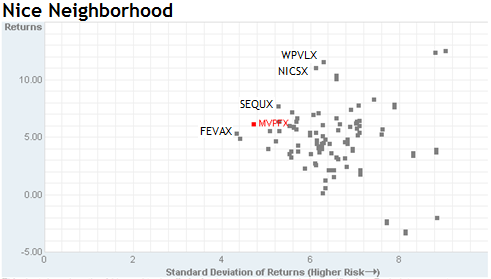

There are, of course, reasons for caution. First, like Mr. Walthausen’s other funds, this has been a bit volatile. Beta (1.02) and standard deviation (17.2) are just a bit above the group norm. Investors here need to be looking for alpha (that is, high risk-adjusted returns), not downside protection. Because it will remain fully-invested, there’s no prospect of sidestepping a serious market correction. Second, this fund is more concentrated than any of his other charges. It currently holds 40 stocks, against 80 in Small Cap Value and 65 in his last year at Paradigm Select. Of necessity, a mistake with any one stock will have a greater effect on the fund’s returns. At the same time, Mr. Walthausen believes that 80% of the stocks will represent “good, unexciting companies” and that it will hold fewer “special situation” or “deeply troubled” firms than does the small cap fund. And these stocks are more liquid than are small or micro-caps. All that should help moderate the risk. Third, Mr. Walthausen, born in 1945, is likely in the later stages of his investing career.

Bottom line

There’s reason to give Walthausen Select careful consideration. There’s a quintessentially Mairs & Power feel about the Walthausen funds. In conversation, Mr. Walthausen is quiet, comfortable, thoughtful and understated. In execution, the fund seems likewise. It offers no gimmicks – no leverage, no shorting, no convertibles, no emerging markets – and excels, Mr. Walthausen suggests, because of “a dogged insistence on doing our own work and reaching our own conclusions.” He’s one of a surprising number of independent managers who attribute part of their success to being “far from the madding crowd” (Malta, New York, in his case). Folks willing to deal with a bit of volatility in order to access Mr. Walthausen’s considerable skill at adding alpha should carefully consider this splendid little fund.

Website

Walthausen Funds homepage, which remains a pretty durn Spartan spot but there’s a fair amount of information if you click on the tiny text links across the top.

© Mutual Fund Observer, 2014. All rights reserved. The information here reflects publicly available information current at the time of publication. For reprint/e-rights contact us.