Dear friends,

Welcome to the New Year.

If you think contemporary politics are crazy, ask yourself “why is January 1 the start of the year?” Ancient cultures tended to align their calendars with the rhythm of the natural world: solstices, equinoxes, the waxing and waning of the moon, planting seasons and harvests. January 1 aligns with, well, nothing.

Which was the point. The ancient Roman had two calendars running simultaneously. The joint rulers, called consuls, took office around January 1 after the week of solstice celebrations. That began “the consular year.” The religious calendar recognized spring as the beginning of the new year, so New Year’s Day fell in late March. In an odd bit of anarchy, their calendar contained 10 months (hence “December” is “10th month”) and 304 days; the remaining days of the year were recognized but weren’t assigned to any month. They were just days.

Weeks tended to last eight days.

And the months? They varied in length, based on how many days the chief priest thought that month needed. Every couple years they’d toss in an extra month (an intercalary month) to realign the civil and solar years. But they didn’t always announce those events in advance; on the first day of the month (the kalend of the month), typically on a new moon, the pontifex maximus would share word of that month’s shape and length. If the pontifex didn’t like what the government was up to, he might trim a few days off the month or declare a couple extra religious holidays when the government couldn’t be in session. Politics screwed up the calendar so badly that, according to Suetonius, harvest festivals occurred months before havest.

All of which only applied in Rome. The outlying pieces of the empire could follow whatever calendar suited them.

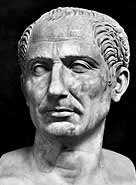

Then Julius Caesar put an end to (almost) all that foolishness. In 46 BCE (they would have called it 708 AUC, “after the founding of Rome”), he stripped the priests of their ability to control the year, aligned the new year with the start of the January 1 consular year and imposed a 12-month, 365-day calendar. That all made 45 BCE a tough year because, to get everything lined up again, he had to add three extra months; an old-style intercalary month at the end of February and two newbies between October and November. (But just once, so don’t get used to it.) Then he announced that all the world had to surrender their native calendars, showing that the power of Rome was so great that even the year bent to its will.

Then Julius Caesar put an end to (almost) all that foolishness. In 46 BCE (they would have called it 708 AUC, “after the founding of Rome”), he stripped the priests of their ability to control the year, aligned the new year with the start of the January 1 consular year and imposed a 12-month, 365-day calendar. That all made 45 BCE a tough year because, to get everything lined up again, he had to add three extra months; an old-style intercalary month at the end of February and two newbies between October and November. (But just once, so don’t get used to it.) Then he announced that all the world had to surrender their native calendars, showing that the power of Rome was so great that even the year bent to its will.

Politics and pragmatism, religion and dogma: they’ve very old games, which we’ve played, lamented and survived for a very long time. In the meanwhile, life goes on, driven by the relationships we build, the attention we pay and the joy we share.

There is much to be joyful for.

It’s deceptively easy to believe that our world is going to hell in a handbasket because the only thing we hear each day is that day’s horrors. Someone got shot. Somewhere got poisoned. Something blew up. Why all the bad news? Two reasons:

- News media report on what’s new; that is, they tell us what happened today that was different from what happened yesterday. They’re looking at individual occurrences, especially if they come with striking visual images. We’re not asked to think about the big picture, because the big picture didn’t happen today. And so we fixate on all the little things that did transpire.

- Bad news sells; more particular, bad news delivered in a howling tone generates outrage and clicks. If you’re looking for evidence, look no further than any headline which also contains the words “Obama” or “Trump.” As in “Obama’s final, most shameful legacy moment.” Or “Trump and the ‘hideous monstrosity’ that was 2016.”

Bad news for fans of bad news. We share the planet with 7.4 billion people, almost all of whom are warm, caring and funny. And almost all of whom are working like dogs to make their lives and their neighbors’ lives and their children’s lives better. Andrew Foster, manager of Seafarer Overseas Growth & Income (SFGIX), travels to some of the world’s poorest nations. “These are deeply dysfunctional economies with unreliable capital markets, but we all knew that ahead of time. What really strikes me,” he said, “is how incredibly hard even the poorest people will work to give their children hope for a better life. What they’re willing to do is incredible and humbling.”

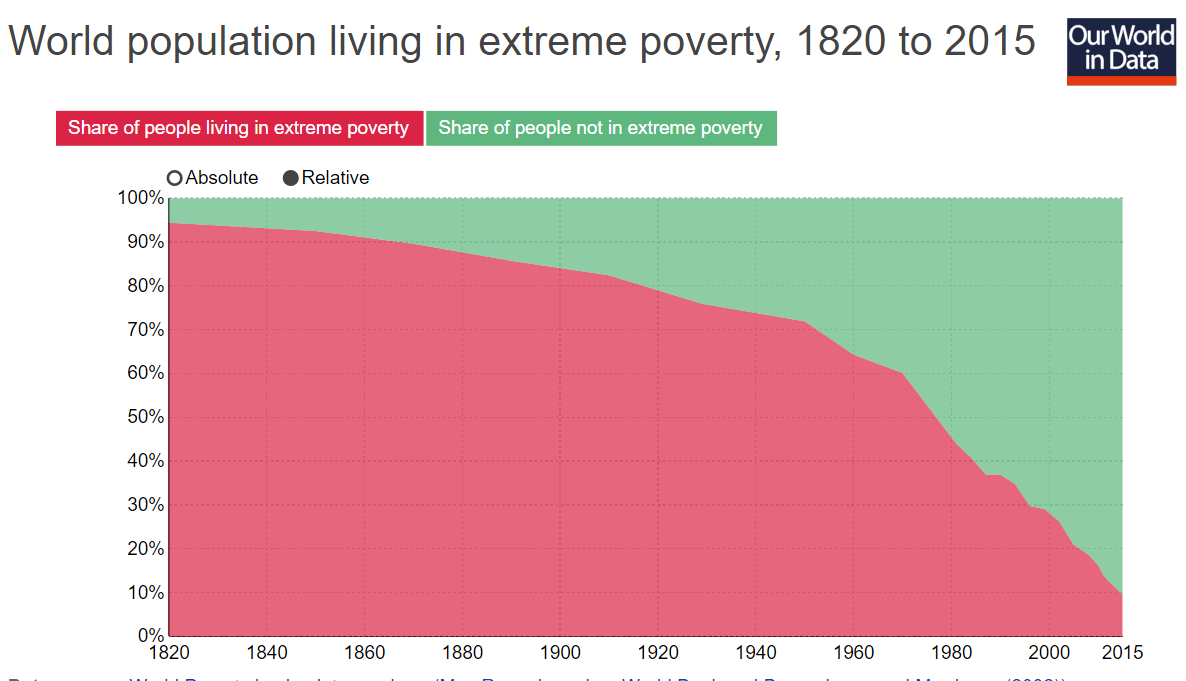

And it’s working. Oxford economist Max Roser, founder of the Our World in Data project, provides compelling evidence for that claim. Rather than focusing on today’s noise, he and his team look at data to pursue the question. “how are things changing?” One of his most striking displays concerns extreme poverty. “Extreme poverty” is defined as living on the equivalent of $1.90/day or less, an amount that’s adjusted to account for non-monetary income (trading for carrots), cost of living across time and so on. Here’s the picture:

Dr. Roser offers this explanation of the picture.

In 1820 only a tiny elite enjoyed higher standards of living, while the vast majority of people lived in conditions that we would call extreme poverty today. Since then the share of extremely poor people fell continuously. More and more world regions industrialised and thereby increased productivity which made it possible to lift more people out of poverty: In 1950 three-quarters of the world were living in extreme poverty; in 1981 it was still 44%. For last year … the share in extreme poverty has fallen below 10%.

That is a huge achievement, maybe the biggest achievement of all in the last two centuries. It is particularly remarkable if we consider that the world population has increased 7-fold over the last two centuries … In a world without economic growth, such an increase in the population would have resulted in less and less income for everyone; a 7-fold increase in the world population would have been enough to drive everyone into extreme poverty. Yet, the exact opposite happened. In a time of unprecedented population growth our world managed to give more prosperity to more people and to continuously lift more people out of poverty.

I’m struck less by the fact that things are getting better, more by the fact that they’re getting better faster which is marked by inflection points around 1950 and 1970. The same pattern holds for global literacy, child mortality, education, fertility and even respect for human rights.

Dr. Roser is struck by the question, “why don’t we know this?” That is, why do so few of us see what Mr. Foster and Dr. Roser see, billions of people succeeding?

Things are getting better.

Not every thing. Not every day. But the important things are, year after year, decade after decade, century after century, getting better. They’re getting better because it’s in our nature to seek better, rather than to surrender to worse.

Our challenges are very real (and, in the case of global warming, terrifying). But they’ve been very real (and terrifying) for centuries. The question is not “will things get better?” so much as “what’s your plan to make your slice better in 2017?” Will you plant a rain garden or volunteer in your schools? Will you walk more, smile more, notice others more? Will you spend less time with your portfolio and more with your neighbors? Will you fuss less about this quarter’s returns and more about the pattern of intentional consumption and serious saving that will support your most important goals?

I have faith in you.

The 2% challenge

2016 was a good year for the Observer. We upgraded our servers to give you faster, more reliable access. Chip and Andrew redesigned the site into our new magazine-like format. Charles has done amazing work in making MFO Premium more sophisticated and more responsive to our readers’ needs. We continue to attract about 25,000 readers each month and came very close to cracking the 30,000 reader threshold in December.

We manage that with the financial support of about 1% of our readers, counting all of the folks who’ve contributed online or by check (though not the uncounted number who’ve used our Amazon link). Some of those folks have been wildly generous and stalwart through the years. We are endlessly grateful to them.

We offer three rewards for folks who contribute $100 or more to MFO in any year: our thanks, the satisfaction of knowing that you’re supporting other readers’ attempts to learn and grow, and access to MFO Premium. MFO Premium is MFO’s other site; it consists primarily of a remarkable set of data (from Lipper) and a suite of tools (designed by our colleague Charles Boccadoro) to allow you to make sense of the data.

MFO Premium is distinguished from other suites in two ways. First, it takes you miles beyond the simple-minded “who’s up the most in the past 3 years?” screeners that are generally available. It allows you to screen for significant time periods (for example, to look at performance in downmarket cycles or bear market months), to look at risk (maximum drawdowns, for example) and risk-return measures (Sortino and Martin ratios) that you rarely get to see, and to examine the correlations between funds. Second, it is constantly evolving. Charles is in almost-constant conversation with readers who are seeking clarifications, improvements or new features. He’s added several (including the correlation matrix) in 2016 and has more planned (including performance over rolling time periods) for 2017. Despite all that, it’s drawn only a couple hundred users.

Charles is, frankly, baffled.

We’d like to raise that to 2%, which would translate to around 500 people, including new and renewing members of MFO Premium, all told. It’s a simple, painless, satisfying process: contributions to MFO are mostly tax-deductible (our attorney says I must repeat the phrase, “consult your tax adviser”) because we’re incorporated as a 501(3)c charity. We’re also an efficient 501(c)3 since our fund-raising costs are, well, zero. If you contribute $100 or more, Charles gives you immediate access to MFO Premium with all the attendant data and support.

Please do. In support of our 2% goal, I’ll update folks monthly on our progress. (In technical terms, it falls somewhere between “guilting” and “nagging,” edging, I fear, toward “annoying.”)

Could you help a child?

We received an interesting query from Doug, a reader in Florida who once worked in the broker-dealer end of the fund world. Doug’s son is autistic and has received profound delight and peace in playing, for the last decade, with a conference giveaway from the Munder Funds.

Lots of flashing blue lights but it’s now stopped working. New batteries didn’t fix it and Doug’s son is inconsolable. Doug knows nothing about the name or manufacturer, except for the Munder Funds name on the side.

If you have any idea of where he might find another or who made it, would you drop me a note? If I hear anything promising, I’ll surely pass it along to Doug.

And thanks!

Speaking of thanks …

Our supporters have been extra generous over the past month. We give thanks to all of you: Victoria, Nancy, Ben, Laurie and Leah – who renewed her MFO Premium subscription and added some extra support. We’re grateful to you all and we really enjoy the notes (Joe waves to Ed!) and cards you include. Thanks too, to Fitz, Kevin, Paul, Ed, Mary, Charles, Altaf and Rick. We couldn’t do this without your support. As always many, many thanks to our now four (!) regular subscribers, Greg, Deb, Jonathan, and Brian. If I’ve failed to recognize you, blame it on New Year’s Eve and a 650 mile drive home from Pittsburgh. I’m a bit tired, but still heartened by your support.

As ever,