“In investing, what is comfortable is rarely profitable.”

Robert Arnott

“An investment in knowledge pays the best interest.”

Benjamin Franklin

MFO profiled Alpha Architect’s US Quantitative Value ETF (QVAL) in December 2014, shortly after the fund’s launch and after our colleague, Sam Lee, praised QVAL’s strategy in a Morningstar piece, entitled “A Deep Value Quantitative Hedge Fund Strategy.” The firm’s CEO Wes Gray first impressed us during his presentation “Beware of Geeks Bearing Formula” at Morningstar’s ETF Conference in Chicago earlier that same year.

I had a chance to visit Wes, his partner and CIO/CFO Jack Vogel, and the rest of his team recently at the Alpha Architect office in Broomall, Pennsylvania. The picturesque town is nearby Bryn Mawr, Haverford, and Swarthmore Colleges; Villanova and Drexel Universities; and The Wharton School of University of Pennsylvania. Wes earned his PhD from University of Chicago, with Nobel Prize Winner Eugene Fama serving as his adviser, and he taught at Drexel. Jack earned his PhD from Drexel and he taught at Villanova.

The office is literally a converted basement in Wes’ home. Approaching the address, I observe six cars parked tightly at top of driveway, as if not wanting to call attention to the neighborhood business managing nearly $1B in assets. The headquarters of behemoth Vanguard, the industry’s largest fund provider at $5T in assets, is just 15 miles away in Valley Forge.

Inside, I find an open arrangement of seven single desks and attendant Bloomberg terminals. There are no private offices. Its “conference room” contains not much more than a well-worn whiteboard and folding chairs; it doubles as the office coffee room. Wes’ garage is the staff gym and weight room. He is an ex-Marine and last year hiked 28 miles near a Pennsylvania army base lugging a 40-pound pack, as described nicely by Landon Thomas Jr in the NY Times article “Hiking Mountains, Gladly, With a Marine Turned Fund Manager.”

Changes since our 2014 profile? Plenty …

- Launched four ETFs, beyond US Quantitative Value (QVAL):

- International Quantitative Value ETF (IVAL), December 2014

- US Quantitative Momentum ETF (QMOM), December 2015

- International Quantitative Momentum ETF (IMOM), December 2015

- Value Momentum Trend ETF (VMOT), May 2017.

- Published two books, beyond Quantitative Value: A Practitioner’s Guide to Automating Intelligent Investment and Eliminating Behavioral Errors:

- Increased assets under management (AUM) from $200M to $975M, split roughly 50/50 between ETFs and separately managed accounts (SMAs).

- Re-categorized their ETFs as “passive with self-indexing” versus “active” and, in fact, Tao Wang is now the only staff member listed as “portfolio manager.” Wes and Jack are now “index managers.”

- Similarly, increased transparency and simplicity by dropping the “ValueShares” and “MomentumShares” branding labels. All funds are now carry only the Alpha Architect brand. (Special thanks here to Ryan Kirlin, who worked at RevenueShares until they were bought by Oppenheimer Funds, and is now the principal interface to market makers for Alpha Architect.)

- Increased adviser investment, based on the January 2018 SAI Wes has over $100K invested in QVAL, IVAL and VMOT and over $50K in QMOM and IMOM. He reasserts that a lot of the family money from the firm’s employees is invested in its funds. Jack politely reminds me that “none of us came from money when we started.”

- Wes co-hosts a podcast called “Behind The Markets” with colleague, friend and neighbor Jeremy Schwartz, Director of Research for Wisdom Tree.

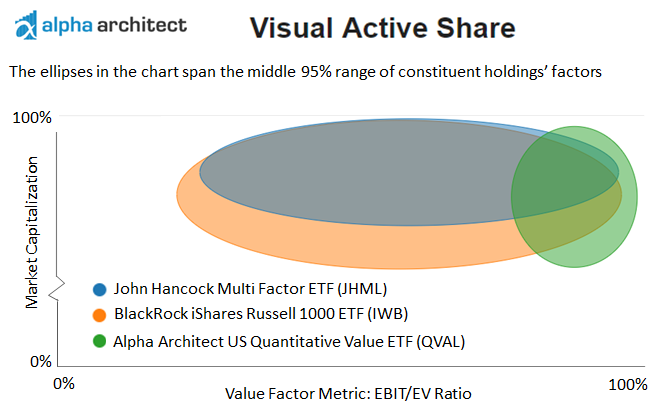

- Jam-packed its website site, if a bit frenetically: chock-full of free research papers, their own and others, an active blog, and DIY investing tools, including the brilliant and elegant “Visual Active Share” tool, which provides “at-a-glance” insight into the characteristics (P/B, EBIT/EV, market cap, etc.) of the holdings of US ETFs. Like the active share metric, it helps call-out closet indexers … only better. Elisabetta Basilico of Academic Insights on Investing calls it her favorite tool for deciphering whether funds are “delivering what’s promised” … what they’re advertising … what a fund is “selling versus doing.”

I’m not inside the door a minute, backpack still in tow, before bringing up their newest fund. VMOT is a fund of funds that uses the four other funds as building blocks: focused value and momentum factor-based building blocks … the two factors that historically have demonstrated the highest return premium. VMOT employs a trend-following system to trigger hedging and dampen volatility, specifically extreme drawdown or “tail-risk.” There are two levels of hedging: 50% and 100%, the latter being market neutral. The trend period is based on a 12-month window, which nicely mitigates extended drawdowns like those experienced in 2000 and 2008. (See “10 mo SMA Method In Down Markets.”)

I mention that it has performed extremely well out of the gate and seems to be the culminating and definitive product that the other funds were developed for. Jack concurs. He also confirms that no other ETFs are planned currently. “We are happy to focus on these five.”

All five funds maintain a 0.79% expense ratio, including VMOT, which (after waivers) does not charge a management fee. Like QVAL, all five strategies and their employment are systematic, transparent, and based on academically vetted evidence. There is no ad-hoc decision making or active override, which is “fraught with behavioral biases.” Wes says the QVAL model has not been changed or tweaked since launch. The basic four ETFs are all concentrated, long only equity, fully invested with some 40 holdings each.

In the conference room, Wes is pulling up the Visual Active Share of John Hancock Multi Factor ETF (JHML). “What does this fact sheet say?” he asks skeptically. It states the fund will “emphasize smaller companies, lower valuations, and higher profitability.” But, in fact, “it does none of these things! And these guys are DFA, known for managing money of Nobel Prize winning economists!” The image below reveals the fund’s holdings shadow the Russell 1000 index in both capitalization and valuation, the latter based on the metric EBIT/EV or earnings before interest and taxes divided by enterprise value.

Wes takes pride in the firm’s low overhead, not just in its office space, coach-class travel routine, and no-flash/no-pretense culture, but also in the refusal to pay distribution fees. “Our funds are bought, not sold,” he emphasizes. He references a recent article by Morningstar’s oracle John Rekenthaler, entitled “Revenue Share: The Fund Industry’s Dinosaur.” Here are John’s key passages:

- Most companies that distribute funds (through online platforms, their staff of financial advisors, or both), expect to be paid by fund companies. Effectively, the fund company overcharges its customers, the distributor undercharges, then the fund company cuts a check to the distributor to settle the difference.

- This subterfuge rests with investors. As a general rule, they shun overt charges–brokerage commissions, account fees, and so forth. In contrast, they are relatively insensitive to asset-based arrangements, where their payments are collected quietly, behind the scenes.

- The artifice is a poison. It abets dishonesty. There isn’t any way that a distributor can tell its customers, “We selected these funds, in part, based on the size of the payment that we receive from their underwriters.” That is no way to inculcate trust.

- Open hands is where the investment business is heading, albeit slowly. Eventually, funds will be sold as stocks currently are.

- Investors have rewarded firms for engaging in revenue share. But those days are changing. B shares are out, and (relatively) clean ETFs are in. Gradually, slowly, revenue share is on its way to extinction.

Wes also references a darker and deeper piece he and Jack posted, entitled “Distribution Economics: Understanding Wall Street’s Conflict of Interest Problem.” It discusses the shift from banks offering only their own financial products to now getting kickbacks to offer products from others. Under a revenue sharing arrangement, instead of directing trades to the bank, the fund agrees to share a portion of its management fees with the bank. The bank maintains profits by awarding scarce “shelf space,” and the fund gets distribution on the bank platform. Generate a lot of fees for the bank? Earn more shelf space! Even if better products get pushed off. It concludes with a reminder: “Fiduciary responsibility matters in financial services more than in any other product category outside of urgent medical care.”

The good news is investors, particularly younger investors, are becoming more aware. Ryan calls it “the feedback loop” phenomenon. Basically, financial information is available today like never before, facilitating performance comparisons of individual portfolios, with your financial adviser or 401K plan, and those offered elsewhere. Every month, it is getting harder for financial firms to bury hidden fees in fine print of fancy factsheets and brochures.

As for competition, Wes believes the business model pursued by Alpha Architect would be hard to replicate and he sees little motivation for anyone to try, certainly not larger players who would not be willing to risk up-front capital at this point. “We’re a low scale trade in an uber niche segment. It works for us because of our low overhead and it’s our passion, but to any of the substantial players out there, it’s a shitty business model … not to mention career risk.”

The firm spends a lot of time educating investors. While the desire to understand financial markets, be open and give-back is pervasive in the culture of Alpha Architect, they acknowledge the outreach is also an opportunity to tout its own products, and perhaps more importantly, it’s an essential provision for attracting the right kind of investors. Basically, investors need to fully understand the underperformance risk the firm’s strategies are likely to incur, at least across shorter investment horizons. (See “An Introduction To Alpha Architect.”)

This past year through February, for example, QVAL has been exceptional. Of the 131 funds Lipper identifies in the MultiCap Value category, QVAL ranked No. 2 and it enjoyed top quintile risk-adjusted performance across multiple metrics, including Sharpe, Sortino and Martin ratios. Below, from the MFO Premium site, are the top five funds based on absolute return, along with the largest fund by AUM, BlackRock iShares Russell 1000 Value ETF (IWD), and the worst performing fund, Fairholme (FAIRX), which is actively managed by deep value investor Bruce Berkowitz … FAIRX’s 13.2% annualized 10-year return through December 2009 earned him Morningstar’s Fund Manager of the Decade award for domestic equity (click table to enlarge).

In back tests before launch, as well as the implemented strategy in its SMAs, QVAL delivered similarly impressive results. But for the two years following QVAL’s launch, investors experienced the downside of a concentrated, factor-focused (“actively managed”) strategy. “Yeah,” Wes confirms. “We called the top at launch.” It dropped 25% versus 13% in category when the market swooned in early 2016 and remained underwater for 29 months, which is hard under normal market conditions but nearly impossible to reconcile during one of the longest bull markets in US history. VMOT, on the other hand, and to a lesser extent IVAL, have enjoyed strong performance since launch. (Morningstar gives IVAL 5 stars in the Foreign Large Value category.)

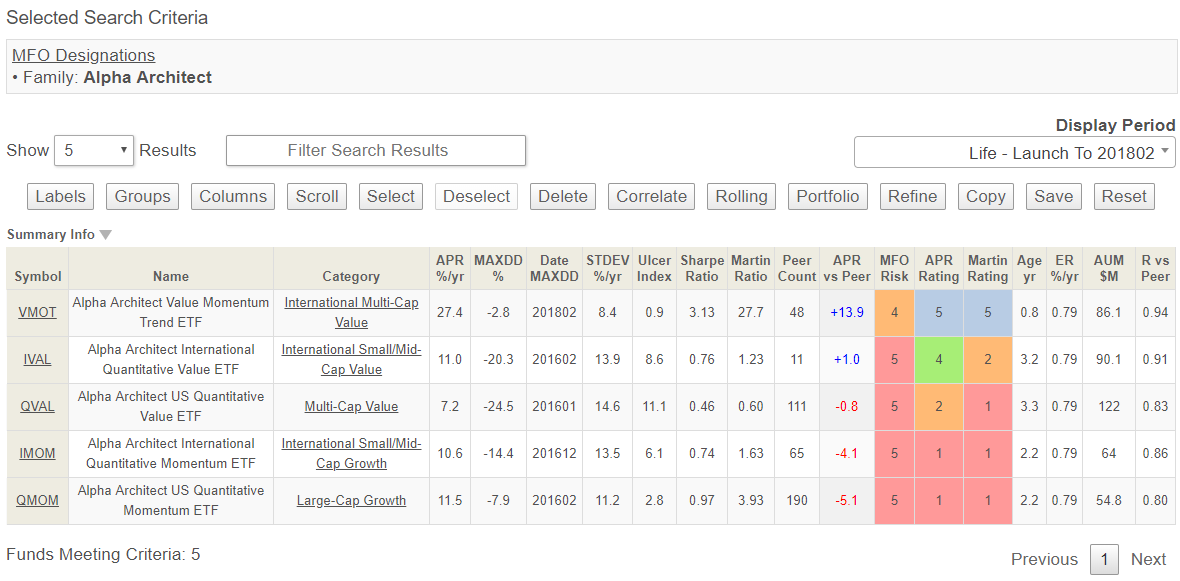

Here’s a quick performance summary of each of the five Alpha Architect ETFs since launch, which varies from 9 months for VMOT to 40 months for QVAL (click table to enlarge):

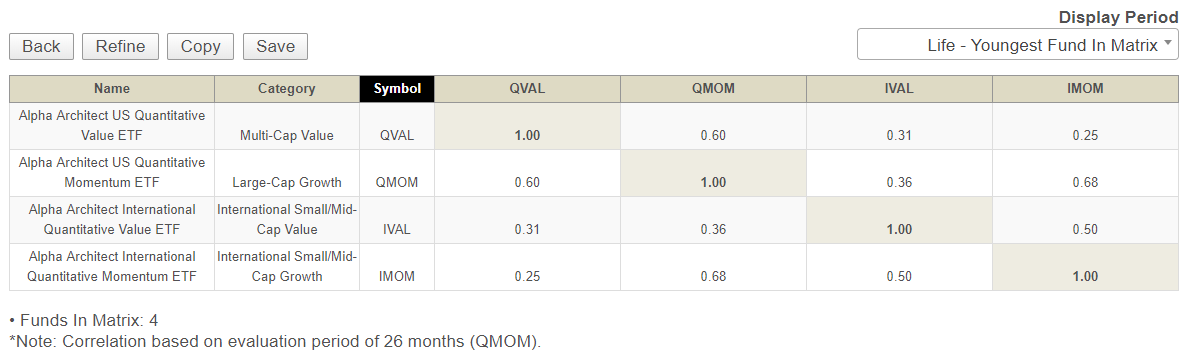

The correlation matrix of R values for the four underlining funds in VMOT shows rather uncorrelated behaviors, which I would expect and bodes well for the fund of funds diversification (click table to enlarge):

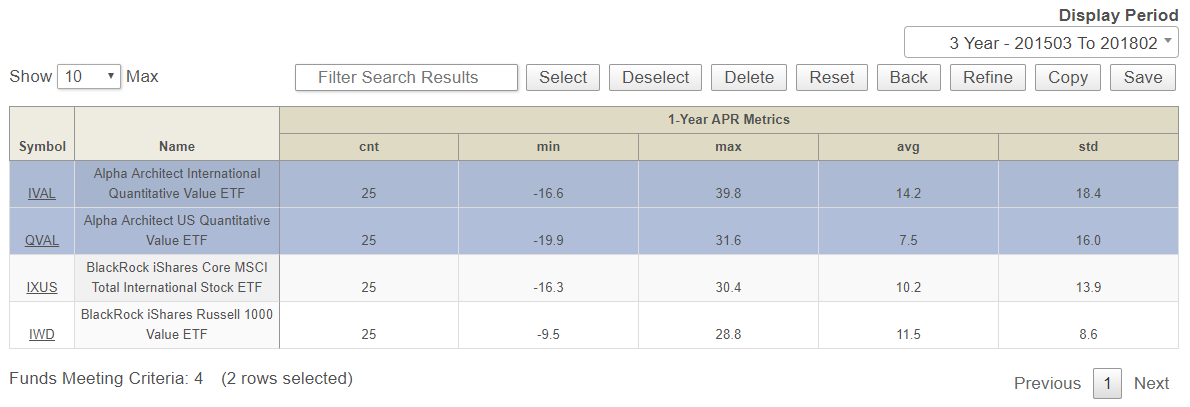

Finally, below is the 1-year rolling average performance of QVAL and IVAL over the past 3 years, along with IWD and BlackRock iShares Core MSCI Total International Stock ETF (IXUS) for comparison. There are 25 1-year rolling periods and the table shows the minimum, maximum, average, and standard deviation in absolute annualized return percentage. Despite some healthy drawdown, both funds have enjoyed even healthier upside, but you must be able to handle substantially higher year-to-year variation than the market (click table to enlarge).

What was supposed to be a 2-hour visit tops, turned into three days thanks in part due to Wes’ invitation to the Democratize Quant hosted by Alpha Architect and Villanova University, and in part due to a late nor’easter that dropped 13 inches of spring snow … it provided a good excuse to stay present. Many participants could not attend in person (eg., Jeremy Siegel Skyped-in from Toronto after his flight was cancelled … for a delightful “fireside chat” with his former student Jeremy Schwartz). But Bloomberg’s Eric Balchunas attended, giving his usual outstanding overview of “The ETF Landscape,” as did Barry Ritholtz, Corey Hoffstein of Newfound, Liqian Ren of Vanguard’s Quantitative Equity Group, Bridgeway’s CEO Tammira Philippe, and Chris Meredith of O’Shaughnessy Asset Management.

Alpha Architect has posted a nice summary of the event, including presentations, in “Democratize Quant Recap,” as did attendee Jack Forehand of Validea in “Lessons from a Quantitative Investing Conference.”

The conference represented a sort of touchstone to the practitioners and investors in quantitative financial analysis, particularly factor based, which has become the new active, supplanting traditional fundamental, boots-on-ground strategies practiced by the likes of Benjamin Graham, Warren Buffett, Peter Lynch and Bruce Berkowitz. Similar to when Buffett was feared to have lost his touch heading into the late ‘90s, or Dodge & Cox in 2008, or Sequoia Fund (SEQUX) in 2016 … once considered the greatest fund ever, my sense is that many of the attendees at this conference, at some level, needed to be reassured as to “Why Do These Strategies ‘Work’ In The First Place?” The team at Alpha Architect will never stop asking.