The typical American of today has lost all the love of liberty that his forefathers had, and all their disgust of emotion, and pride in self-reliance. He is led no longer by Davy Crocketts; he is led by cheer leaders, press agents, word-mongers, uplifters.

H.L. Mencken, “On Being an American” (1922)

As we move forward, now more than half-way through the first quarter of 2019, it has been interesting to watch the change in psychology among investors, both individual and institutional. We have gone from fear of a bear market with all that that might entail in terms of wiping out permanent capital to fear of missing the train perhaps leaving the station as we either start the next leg up of a bull market, or perhaps start a new bull market. Some of that is a mindset of trying to make back some of the losses that, in a panic mode, investors might have realized. Some of it is a recognition that, with the Federal Reserve is less willing to continue raising rates as originally laid out under a new chair in 2018, the only game in town may be a return to equities.

In that vein, one of the most interesting disclosures was the write-down of assets by both Berkshire Hathaway, as well as investor group 3G Capital from Brazil. This reflected their assessment of the current value of the Kraft-Heinz brands, as impaired by changes in tastes and habits of the food shopping public. That is the rationale as to why Mr. Buffett has had a rare toe stub.

The reality is somewhat more complex than that. The argument in favor of investing in consumer branded food companies has been that the brands had a cachet. They often related to the childhood memories of the consumer, which allowed for pricing power over alternatives in the marketplace such as private label. And under that umbrella, from a capital allocation view point such companies would be able to dedicate a large part of the cash flows to REINVESTMENT in the brands, providing for a constantly growing annuity from those investments.

The reality is somewhat more complex than that. The argument in favor of investing in consumer branded food companies has been that the brands had a cachet. They often related to the childhood memories of the consumer, which allowed for pricing power over alternatives in the marketplace such as private label. And under that umbrella, from a capital allocation view point such companies would be able to dedicate a large part of the cash flows to REINVESTMENT in the brands, providing for a constantly growing annuity from those investments.

What changed? Well, first, the nature of the competition. If you go back some twenty-odd years, private label was a matter of horrible packaging (black and white cheap cardboard), often placed in a separate aisle from the rest of the store, and often less clean than the rest of the store. And that was before one got to the ingredients used, and the resulting taste of the product. The intent was pretty much to provide a product that no consumer would want to purchase or consume. The consumer would hopefully run screaming to other parts of the store to purchase the traditional branded items.

Fast forward five to ten years, and one of the things that happened was Walmart. They pushed constantly on the branded manufacturers to cut their wholesale product prices to Walmart. The end result was that Walmart’s margins would be superior while providing a lower price point for the consumer. And to win and keep Walmart’s business and maintain their own margins, the branded companies found themselves searching for ways to take out costs. We started seeing product reformulations, changes in packaging, and outsourcing of product manufacturing to contract manufacturers to reduce labor costs. We saw the arrival of the investment bankers, with their ideas of synergies that could be obtained by merging companies with complementary product lines. Savings would come from the scale of raw materials purchasing for ingredients, packaging, and manufacturing costs. They would also look for savings in the marketing and advertising costs that were a large factor in the price the consumer saw in the supermarket.

Fast forward another five years. We see a world where pricing power has shifted from the manufacturers to the retailers – the Costco and Kroger companies of the world. First, private label products became brands in and of themselves. No need for advertising and marketing budgets required to support a brand. Kroger is the largest private label manufacturer in this country. Its own plants and sourcing, allow it to control quality while making a margin equal to or superior to the branded companies manufacturing similar products.

The same story applies with Costco – why purchase Hellman’s Mayonnaise when for substantially less you can purchase the Kirkland Costco brand, and it tastes better! And all of this is before we address the question of food inflation. That is a subject not talked about by either political party over the last ten years. As I have mentioned in previous months, it is obvious to anyone who does the food shopping, and sees the dollar purchasing power shrinkage resulting from the packaging shrinkage. And that is before you apply the taste test to the various reformulations.

These trends did not happen overnight. The millennials do shop and eat differently. But by the same token, prior generations also have been forced as a matter of survival to also shop and eat differently. Clearly the Great Recession forced many families to change their food and consumer item shopping habits. And once they switched to, for instance, the Kroger or Safeway private label products in such things as pasta or cereal, there would be no going back when happy days returned.

Now, we do not need to have a tag day for either Mr. Buffett or the people at 3G. They have profited handsomely over time. This should be a wake-up call to them to rethink where appropriate their allocation of capital. But one does wonder about the extent to which these pricing pressures will spread to other areas.

Now, we do not need to have a tag day for either Mr. Buffett or the people at 3G. They have profited handsomely over time. This should be a wake-up call to them to rethink where appropriate their allocation of capital. But one does wonder about the extent to which these pricing pressures will spread to other areas.

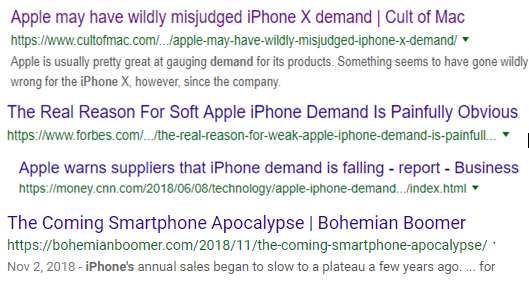

Automobile insurance is a regulated product and a commodity product at the end of the day. Cell phones likewise have the potential to morph into being viewed as a commodity product. What this really means is that we do face, in the investment world, the continuing potential of not just technological disruption, but also brand disintermediation in areas where we never thought we would see intense price and product competition arising.