Technically, 10,315,656 miles high.

The IMF reported in October that global debt, government, corporate and individual, is now $152 trillion. (That’s $152 followed by 000,000,000,000.) That’s historically high, both in absolute terms and relative to global GDP. And it’s not limited to slow-growing developed economies; increasingly emerging markets are issuing debt at a record pace.

Folks at the Endowment for Human Development, who have either spiffy calculators or too much free time, calculate that a stack of $152 trillion one-dollar bills would stand ten million miles high.  Laid end-of-end, they’d stretch 14.4 billion miles. That is, to Pluto.

Laid end-of-end, they’d stretch 14.4 billion miles. That is, to Pluto.

And most of the way back.

That wasn’t supposed to happen. The watchword after the global financial crisis was “deleveraging.” In simple terms, paying down your debts. Debt-driven spending set the stage for the 2007-09 crisis and, in its aftermath, people were supposed to get prudent, pay off their credit cards, balance their national budgets, and finance corporate operations from free cash flows. Prudence would, in the short term, depress global growth by depressing demand. But, in the long term, it would better position us for strong, sustained growth.

Good luck with that.

Instead of deleveraging, we’ve added $50 trillion in debt since the start of the crisis, raising the global total from $102 trillion to $152 trillion. Why? Central bankers were terrified of the prospect of a global depression, perhaps a new dark age.

They first drove rates toward zero, then to zero, then below zero. There are now $10 trillion in negative interest rate bonds in circulation, primarily in Europe.

In 1932, a Saturday Evening Post reporter asked the great British economist John Maynard Keynes if there had ever been anything like the Great Depression. Keynes replied, “Yes. It was called the Dark Ages and it lasted 400 years.”

People responded rationally by borrowing more because savings didn’t pay (the five-year return on Vanguard Prime Money Market VMMXX is 0.10%) and lenders were pretty much giving money away. Investors, professional and otherwise, started buying riskier assets (dividend-paying stocks, for example) to try to earn enough income to cover their obligations. And governments rushed to capitalize. Belgium and Ireland have now issued their first 100-year bonds. Austria is selling 70-year bonds. Italy, Spain, France and Belgium all sold 50-year bonds this year. Those bonds are paying less than 1.2%.

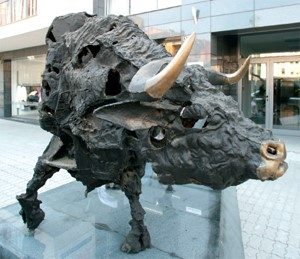

“Most hated bull market”

A search for the phrase “most hated bull market” returns 4700 results. That reflects the received wisdom that this is the MHBM. Wall Street’s cheerleaders call on you to “love the bull.”

Bull indeed.

It’s more accurate to call it the “most despised bull market” instead, because that captures analysts’ disgust with it. At base, this bull should have died four years ago from weak fundamentals and high prices. Instead, it staggers on.

It is The Zombie Bull Market, animated by unholy practices: low interest rates make borrowing free, executives use borrowed money to underwrite stock buybacks and dividends which, for now, makes their shareholders and themselves rich.

That makes sense only if you think inflation will average under one percent annually for the rest of this century (perhaps because of the aforementioned dark age). If inflation exceeds 1.2%, you lose money. And if interest rates go up, you lose a lot of money.

The rule of thumb is that a 1% interest rate rise depresses the value of a bond portfolio with an average maturity of 10 years by 10% and a 30-year portfolio by 30%. One wonders what the consequences would be for a 100-year portfolio?

Corporations have issued vast amounts of debt in response to the offer of free money and have badly misused the proceeds. J.W. Mason, economist at the liberal Republican Roosevelt Institute, found that only 10% of borrowed money goes into productive use. Much of the rest is used to buy back stock and underwrite dividends. An October 2016 FactSet Research report shows that companies now routinely payout more than they earn. Goldman Sachs concluded that the stock market’s entire return in 2015 was attributable to dividends.

Issuing 10-year debt that produces a one-year “pop” in your stock price makes a world of sense if you’re an exec who’ll be retired or snatched up by another firm in the next three years. It makes rather less sense for those left holding the bag.

If interest rates rise 1%, debtors are going to need to find $1.52 trillion dollars to cover the additional interest payments to their creditors. Bondholders, meanwhile, are going to see the market value of their existing bonds – that is, the amount they could get if they tried to sell them to somebody else – drop precipitously. It’s hard to imagine that this is going to go smoothly. The IMF put it mildly: “financial crises tend to be associated with excessive private debt levels.” On October16, Washington Post economics columnist Robert J. Samuelson allowed that it might “possibly trigger a major financial crisis … [though] whether or how this might become a full-blown crisis is uncertain.”

Traditionally, the stock market’s best period runs from November through early spring. Our collective insistence on electing either The Regular Crazy One or The Catastrophically Crazy One and the temper tantrum likely to follow either outcome, is not helpful. The Fed has reportedly been holding back on a rate increase until after the presidential election, for fear of influencing its outcome. Economists now guess there’s a 70% chance of a rate hike in December. The best argument that stocks aren’t crazy expensive is that they’re still a better value than bonds paying zero. If bonds cease paying zero, that argument is weakened.

What’s an investor to do?

Excellent question! Damned if I know the answer.

Here are our Top Ten recommendations:

- Don’t be stupid. This is not the time to rush into a fully invested, market cap weighted ETF, index fund or closet index. By their nature, they accelerate as we approach cliffs then fall fast and hard when the market goes over them.

- Don’t be stupid. Don’t try to protect yourself by investing in strategies that you can’t explain or, worse, which the manager can’t explain to you.

- Don’t be stupid. Don’t invest with a manager who still has training wheels on; there are a lot of funds being launched that try to escape the all-ETF-all-the-time temptation by offering tricky strategies that have only worked in computerized back-tests but not in the real world. Let them practice with somebody else’s money.

- Don’t be stupid. Don’t wait until you’re in a panic, personal or otherwise, to make a financial plan. Talk it through now. Write it down. Write the paragraph on a piece of paper: “I don’t care what the stock market does when it’s panicked. I won’t let other people’s panic force me into making mistakes. I promise myself and my family that I will not sell anything for the next 12 months.” Then explain it to your family and stick it on the refrigerator door. The inimitable Jason Zweig goes a step further. Keynes was a good investor not because he was always right but because he was always resolute. Drawing on that lesson, Mr. Zweig advises you to “write a bind contract with yourself, witnessed by a friend or family member, committed you to buy more stocks when they fall 25%, 50% or more.” The refrigerator still works as a bulletin board for it!

- Really, resist the temptation to be stupid.

- If the past predicts the future, you could try to ride the dividend-stock wave. Timothy McIntosh argues, in The Snowball Effect (2016) that during the four great bear markets in the past 110 years, “The only reliable way to make positive returns during secular bear market periods is to invest in dividend-paying stocks.” I’m skeptical because dividend-paying (and low volatility) stocks have been dramatically bid up, but I could be wrong.

- Tilt toward what’s cheapest. The Leuthold Group argues that valuations in the emerging markets are downright cheap and that they are, in developed markets outside the US, no higher than “neutral.” That’s led a number of global stock fund managers to lighten their US exposure, if not flee.

- When there’s nothing good to buy, don’t buy anything. That is, hold cash and wait. In the past 12 months, Vanguard Total Stock Market Index (VTSMX) is up 3.5%. Unless you believe things are fundamentally better now, that’s a proxy for the cost of lightening up on your investments; you might miss out on a two or three percent gain. As Jason Zweig observes, “with stocks still not far from their record highs, sitting on some cash is a better idea than ever” (WSJ, 10/14/16).

- Trust your money to the people who have earned your trust. In May 2016, we profiled the Dry Powder Gang, the small handful of fund managers who refuse to put your money needlessly at risk. They are resolute when you are wavering and they have, over time, richly rewarded investors who didn’t get greedy and bolt. This month we’ve tracked down the 25 funds that had the best risk-adjusted returns in the 2007-09 market crisis and identified those which have continued to perform exceptionally during the relentless bull that followed. (See Counting The Winners.)

- Celebrate life. You used to do that more than you do now. You should get back to it. Here’s a start: go out to dinner with your family and intentionally leave your cell phones at home! Eeeeeeeeeee! You can tell that I wrote that suggestion on Halloween. It’s scarier than the headless horseman!