By Dennis Baran

This fund has been liquidated.

Objective and strategy

The fund seeks long-term capital appreciation by investing in an international, all-cap portfolio. The fund is non-diversified and its primary focus is on developed markets. Its strategy is benchmark-agnostic, so its country, industry and sector weightings may differ substantially from those in its benchmark index or peer group. Its process capitalizes on market disruptions, fear, and volatility to generate bargains. The fund plans to hold between 15-50 different companies, may hold substantial cash and is typically hedges its currency exposure when cost effective.

The fund is intended for long-term investors wishing to own a concentrated international value fund, who understand its value-driven philosophy focused on absolute results rather than relative performance, and its flexibility to hold cash when the risks present in the market are more beneficial to shareholders than investments in additional securities.

Adviser

Intrepid Capital Management in Jacksonville, Florida was founded in 1994 by Forrest Travis and his son Mark. Intrepid chose to separate its investment strategy both geographically and philosophically from Wall Street by executing an independent and contrarian approach to money management. The name of the firms identifies what it calls its constant pursuit of absolute value in a fearless and enduring way through the application of rigorous analysis to understand a business, identify when it is selling by at least a 20% discount to fair value, and then waiting patiently for this value to be recognized. The process is applied “without fail” in the effort to make money in up markets and protect capital in down markets. The firm will not buy a company that any of its managers would not own themselves, invests its own money “shoulder to shoulder” with its clients, and holds cash when buying opportunities are not identified. As of 11/30/16, the firm manages $909 million in its six mutual funds, separate accounts, and a hedge fund with most of the assets in its funds.

David Snowball, publisher of MFO, has previously profiled two of its offerings, Intrepid Income (ICMUX) and Intrepid Endurance (ICMAX). Intrepid Funds

Reason for Launching the Fund

Following its previous success in finding undervalued domestic companies – what the firm has done for years – Intrepid started the fund to gain access to a larger investable universe through an international product and one that had been planned for a long time.

The Manager: Chronology and Development

Nominally the fund is managed by a team which is led by Ben Franklin, CFA. As a practical matter, Mr. Franklin now has sole responsibility for the fund’s day-to-day operations. That will be formalized in the next prospectus, which will remove the names of the other team members.

While in high school, Franklin participated in a magnet program called “The Academy of Finance” but had mixed feelings about investments as an area he wanted to pursue. However, while in college, his father gave him a copy of The Richest Man in Babylon by George S. Clason, which changed his future plans significantly. The book had simple financial advice, but what he concluded most of all was the basic idea of having money do the work for you, and the more you know about doing that, the safer your future will be. This belief has guided his strategy in his fund.

While getting his MBA, Franklin fell in love with the value philosophy when he was in a student-managed investment fund allowing participants to apply their knowledge in picking stocks. Benjamin Graham’s The Intelligent Investor resonated with him because it made sense not only practically but also temperamentally. He recalls that his professors – too ingrained with efficient market theory – didn’t give any importance to value investing in response to his questions, and so he continued to embrace the value philosophy by “going down the rabbit hole” on his own.

After finishing his MBA, Franklin’s main goal was to get an equity analyst position and work eventually into a shop that shared his value philosophy. However, he was lucky enough to be hired at Intrepid Capital in January 2008, a firm that already shared his value tilt and contrarian views. He then began as a research analyst before beginning his duties as a portfolio manager of ICMIX.

He received his BBA in Management and MBA in Finance from the University of North Florida.

When Franklin started working at Intrepid Capital, Mr. Jayme Wiggins, current manager of the Intrepid Endurance fund (ICMAX), was working at Intrepid, running the high yield strategy. When he left within a year of Franklin’s hiring for business school and before the crash, Franklin joined Mr. Jason Lazarus, now the manager of Intrepid Income (ICMUX) to manage the high yield strategy, which was still early in their careers. Everyone at Intrepid, he says, handled that time period with impressive poise, and working together with Mr. Lazarus helped with his growth. They both started about the same time and would challenge each other frequently, candidly, but respectfully.

Besides Mr. Lazarus, Mr. Wiggins has also been instrumental in his development as a smart, independent investor who can quickly find the faults in any investment idea and someone willing to help others. Franklin seeks his advice frequently and is a person who makes everyone that much better.

Franklin credits his experience working on junk bonds as helping him to evaluate stocks. That’s because Intrepid’s bond strategy typically includes holding bonds until the company calls them or they mature, and in many cases these are illiquid holdings they couldn’t sell quickly if they wanted to. For this reason, they have always been very diligent in focusing on the downside by knowing what the upside is (yield-to-worst). By doing so, their work is done in finding out what could go wrong and why it is called a negative art.

When investing in cheap and illiquid stocks, Franklin applies the same diligent approach because it’s important to know as many things as possible that could go wrong before purchasing a stock and what he would do in the event this happens. While some people are very capable of remaining calm in turbulent times, he believes it’s even better to be prepared ahead of time. He adds, however, that not all outcomes can be foreseen, and when too many external factors can affect a security, he tries to avoid it altogether.

Concerning the launch of the fund, Franklin says that at first his ultimate goal was to be a portfolio manager of domestic small caps or even micro caps because he believed that this category would offer the best opportunities for finding undervalued stocks, including domestic small cap stocks. However, when the opportunity arose to be a portfolio manager of a small cap international stock fund, he was beyond delighted because it was so close to what he wanted to do.

So how did he handle the complexities of international markets compared to domestic ones?

He spent a lot of time learning the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and looking for simple, easy ways to understand businesses that can be valued with a high degree of confidence – much as he does with domestic companies. Using this process, he has discovered many international companies for potential investment. Also, because his portfolio has few restraints, he can buy undervalued domestic companies as well. If the world is his market, why would he limit himself only to domestic stocks?

Mr. Franklin is the sole portfolio manager of ICMIX. He is joined by Matt Parker, an analyst. They do work together with other managers and analysts across the firm as well. Franklin is responsible for all buy and sell decisions in the fund.

Strategy capacity and closure

Approximately $1 billion, firm wide. While some of the other Intrepid funds occasionally buy its international names, Mr. Franklin has a good feel for their liquidity and investability across the $900 million held at the firm.

Active Share

The fund does not keep an active share statistic; however, it will not look like an index dominated by larger companies because its all cap strategy allows Franklin to look anywhere. At the same time, he points out, suitable international investments are also limited, and so he searches for the best of these, indicating that many value companies are cheap for a reason and “have some hair on them.” Another factor impacting active share is the level of concentration in the fund vs. the index.

Management’s stake in the fund

As of September 30, 2015, Mr. Franklin has between $100,001-500,000 invested in the fund. Of the other two nominal team managers, Mr. Travis has $100,001 – 500,000, and Mr. Wiggins has none. As of December 31, 2015, only one of the fund’s three independent trustees has chosen to invest in it.

Opening date

ICMIX began operations December 30, 2014.

Minimum investment

$2,500 for Investor Class shares and $250,000 for Institutional Class shares, except that Institutional Class shares of the Fund are not currently available for sale.

Expense ratio

1.40% on assets of $17M as of 12/22/16

Comments

Proprietary Research

Mark Travis, CEO of Intrepid, has said, “We use in-house research, refined over 20 years of practice and perfected during some of the most challenging markets of the century, to determine if a company is our criteria for investment. It’s simple, but not easy.” In other words, this is hard-nosed, homegrown research.

Mr. Franklin adds that most managers’ reliance on outside opinions – whether from the sellside, other managers, or some other content generator – is from the human condition needing reinforcement from others and, as such, is a liability and an error in the process. Intrepid’s research begins by reading a company’s annual report and then forming an investment thesis. Because outside opinions are everywhere, he says, it’s very easy to let those seep in after initial exposure, and so they try to avoid any influence until their research is done and their thesis is complete. Also, subjectivity and difference of opinion can easily differ no matter how quantitative investors get.

The criterion for purchasing companies is at least a 20% discount to FV regardless of market cap. The manager also cites research showing that investing in one’s best ideas and in illiquid and unpopular securities, where larger funds are unable to invest, outperform most of all.

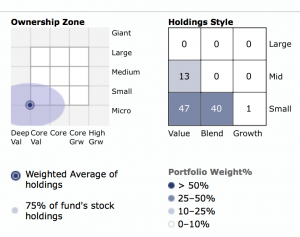

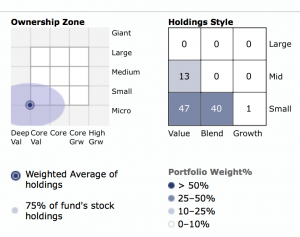

Portfolio Construction: Focus on Small Cap Value

As of 11/30/16, with a median market cap of $396 million, ICMIX is a micro/small deep value fund as shown in the Morningstar style box. However, Franklin doesn’t expect the fund to consistently remain deep value but rather consistently as an all cap fund as is its mandate. While deep value has a place, he personally enjoys buying quality businesses that will compound over time rather than focusing on buying what he calls “cigar butts.” Ideally, he will shift more towards the former but never totally ignore the latter.

Franklin touts the fund’s small size as an advantage because it allows him to purchase smaller securities that would not make sense to a larger fund, as they would not “move the needle.” He has attempted to use this to his advantage and “think outside the box.” Morningstar’s Style Map software agrees because ICMIX literally doesn’t fit inside. Many of his holdings are trading at multiples much lower than what is available in larger securities, resulting in the fund being labeled appropriately. Although some would suggest that posturing a fund in these types of companies is riskier than buying large, well-known companies, Franklin disagrees with this view in the current market environment.

The problem is, he says, that Intrepid requires a margin of safety and that prevents it from investing in good businesses at expensive prices. If a significant market dislocation occurs, then many good businesses he follows may become cheap enough to buy.

Finding Statistically Cheap Companies

Everything Franklin does is based on bottom up analysis. His screening process includes many typical value screens – low multiple of earnings, cash flows, book value, new 52 week lows, and searching for companies below certain EV/EBITDA multiples to find the number of companies that fall within their parameters as being cheap. While this process reveals plenty of potentially investment ideas, the real value added is putting in the hard work going through each name and understanding what’s going on. This can be frustrating because almost every name that looks good at first eventually becomes a pass as more is learned.

Also, he may have to become creative in that process to identify companies that others have overlooked. For example, a company may be trading at a high multiple of current earnings due to the current year’s earnings being depressed but may be cheap if he values it based on normalized earnings. Most important is that finding these companies is only the beginning. Determining their value is completed through fundamental analysis.

Franklin follows over 150 companies on a regular basis for potential purchase and reviews them to see if any have fallen in price significantly and thereby become candidates for purchase. Although he does not have a thorough understanding of all of these companies’ intricacies, he does have a good starting point. Within that list is a smaller one that he knows better, one that is growing, and in which he would invest at short notice if prices fell.

Cash Flows

Most investments that Franklin makes are in companies he expects to be going concerns; therefore, he analyzes earnings and cash flows, valuing these businesses based on discounted cash flows but with some important distinctions.

While more complex, the three basic inputs of DCF are cash flows, the discount rate, and the growth rate. When estimating the cash flow, he attempts to use a normalized cash flow for a business over the business cycle, not forecasting the next five years, and not using the cyclical peak or trough cash flows. Nor does he look at the discount rate in an academic fashion, that is, he does not subscribe to a capital asset pricing model (CAPM) or weighted cost of capital (WACC). Instead, he uses a rate of return that he expects a business to produce on an unlevered basis, typically between 10 and 15%. He knows that he is not going to be right about the growth rate, and for this reason, is typically looking at mature, slow growth companies that are growing at, or near their country’s GDP, and in that way is making an assumption about the country’s long term growth rate relative to a company’s growth rate to it.

The Process at Work: Undervalued Companies, Acquirers, Higher Quality Companies, and Spin-offs

Dundee Series 3 preferred is a significantly undervalued example. While the company is burning some cash, it has significant asset coverage (over 7x), including multiple publicly listed stocks, which he says, they could easily sell to satisfy the principal if needed. Yet, the preferreds are selling at half of their par value and have a 9% current yield and are also floating rate based on the Bank of Canada’s 3-month rate. Duration is not an issue – and their rates are already low – about 50 bps for the 3 month.

Toxfree (TOX AU) is a recent purchase of a serial acquirer. The company is in the waste management industry in Australia but focuses on the treatment of waste rather than stuffing it in some old landfill. Franklin points out that governments continue to push for better waste management practices and that in Australia only about100 hazardous treatment facility licenses exist and are hard to obtain. Because TOX has been acquiring small mom and pop firms that already have these licenses, they have about one-fourth of all licenses in use themselves. Furthermore, the waste management industry has a history of borrowing too much and getting into trouble, but TOX has been prudent in their use of debt and has historically issued equity as part of the deal. These are the types of acquisitions that he believes can add value, that a larger competitor will require these licenses, and that a buyout of the company is likely.

Ipsos (IPS FP) is a higher quality, global market research and consulting firm in France. It has performed well and is trading close to their valuation. Franklin says that while the stock could take off from here because its closest competitor was just bought out, he doesn’t think it would be due to the intrinsic value and purchasing here is more speculative – that is, betting that others will bid it up to a higher multiple as opposed to getting a satisfactory yield over time.

Last, Franklin says that he likes spin-offs and actively investigates them for potential investment. For example, he has made one investment in a spin-off, DeLClima, that was a large success but was unfortunately included only in his seed account prior to the launch of the fund. He says that not all spin-offs are great investments. In general, he believes that most mergers and acquisitions end up destroying capital but also that this view is not a hard and fast rule. He prefers companies that do bolt-on acquisitions that are easier to have things go right.

- On average, he tends to own shares in businesses with more stable end markets

- and without highly leveraged balance sheets, ones where management has a

- substantial stake, there is little debt, and the products are indispensable. These

- can usually be valued with a higher degree of confidence.

So is his philosophy more like Warren Buffet’s or Benjamin Graham’s? That depends, he says, on his estimated margin of safety. At times he would take a significantly undervalued security over a higher quality business trading at only a minor discount, adding that keeping an open mind and not discriminating can produce better investment results.

Evaluating Risk

Intrepid defines risk as losing money. It controls risk by understanding a business’s operating characteristics, cash flows, balance sheet, and the motivations of management while avoiding companies with both operational and financial risk. Then the firm waits patiently to buy shares when there is at least a 20% discount to their fair value estimate.

Franklin uses various methods to include risk in his valuation. The end result is that the valuation is already accounting for the additional risks, and if the stock is still trading at a 20% discount then it is a potential buy. To require a larger discount from here would be double counting. If he thinks a company is on the riskier end, then he uses a higher discount rate to account for it. He accounts for capital intensity via our cash flows, which will be lower due to the required reinvestment. Again, he does not subscribe to WACC. This results in excluding many levered firms because he won’t give them the benefit from accessing capital at lower, tax advantaged rates. While this can be overly punishing at times, it’s better than having company blow-ups. He tries to account for cyclicality with his normalized cash flow and higher discount rate. This results in typically ignoring cyclicals in all but the worst environments.

A broader explanation is that he can value some risks so long as the risk is not too large, but other risks can be too difficult to value, for example, political risk. Another important distinction is not taking on too many external variables. If a company is reliant on multiple factors (e.g. interest rates, oil prices, and global shipping) it becomes too difficult to value with a high degree of confidence.

The one area where he tends to lean towards requiring a higher discount than 20% is on asset valuations. Companies that are generating cash flow will continue to accrue value, even if the stock price is not reflecting it. However, companies with little to no cash flow are not accruing that value, and the longer it takes for the price to represent the value, the lower the return is.

The fund also controls risk by limiting the size of its positions in the portfolio.

Although the fund has no minimum, Franklin doesn’t want to spend time researching a company unless it could be at least a 2% weight in the fund – its typical initial size. He considers 4% a “full weight” for most securities but is willing to go above that for companies that offer the proper type of risk/reward tradeoffs he likes, for example, in Clere AG, a German company that focuses on investments in environmental and energy solutions in Europe.

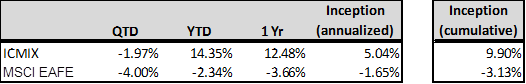

Fund Performance and Relevant Data

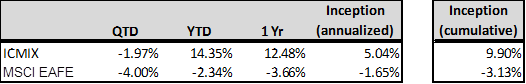

The table below is as of 11/30/16. The fund’s inception date is 12/30/14.

Source: Intrepid Capital

The fund has outperformed its bogey by a wide margin.

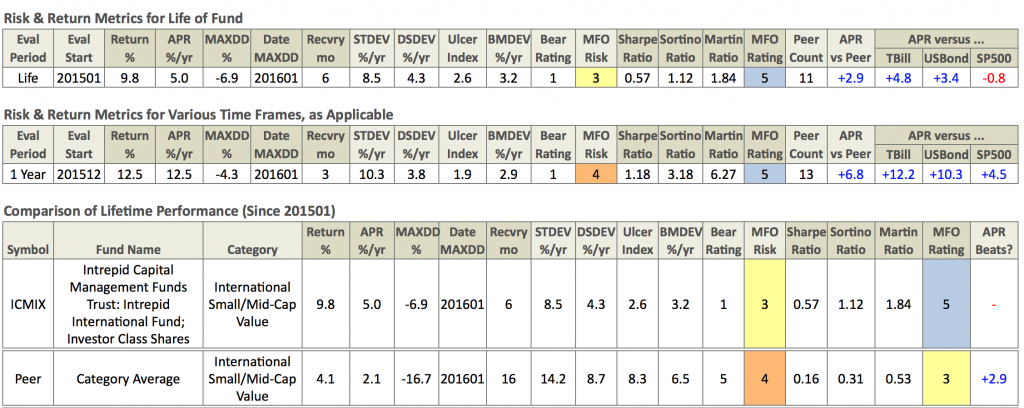

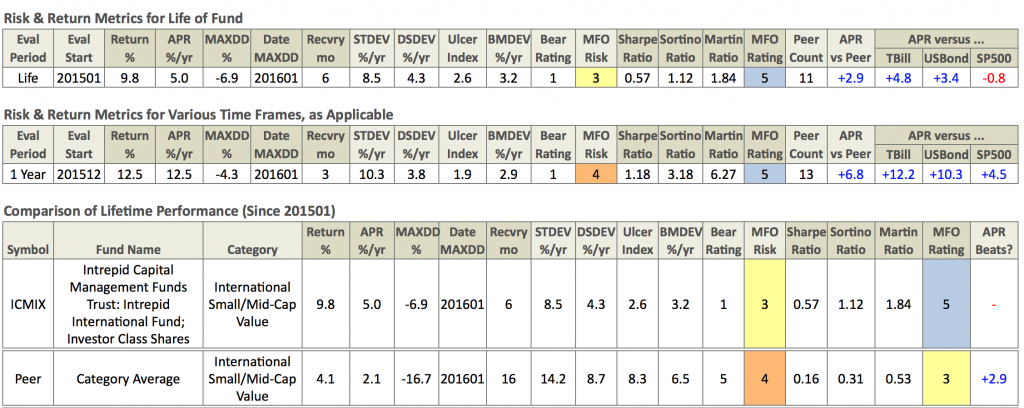

What does an MFO Premium Multi-Search show for the fund?

Currently at 1.9 years, ICMIX falls just short of a two-year history and is classified as a rookie fund (1-2 years old). As of 11/30/16, the short answer is that its lifetime performance and risk metrics are very promising.

While its peer comparisons are interesting, they are also problematic with such a young fund. After sorting through a lot of Morningstar and MFO data, we decided to screen for “rookie funds” in any of the international styles with the MFO Premium Multi-Search tool – small value, small core, and small growth. That gives us a comparison group of 19 funds. Within that group, ICMIX ranks at or near the top.

ICMIX Performance and Risk Metrics against other rookies

|

Performance

|

Sharpe Ratio

|

Sortino Ratio

|

Martin Ratio

|

Ulcer Index

|

Bear Market

|

|

5th of 19

|

3rd

|

2nd

|

4th

|

1st

|

1 (Best)

|

The fund ranks highly after its nearly two-year history against these competing styles by performance and on a risk adjusted basis. Also, its MAXDD at -6.9 ranks second among the group. Its short-term performance based on all of the metrics presented so far is encouraging.

As of mid-December, Morningstar shows the fund having a top decile rank of 5 for one-year and 7 YTD. Its one-year upside-downside capture ratio is 100.77 and 32.17 as of 11/30/16.

But investors need to be mindful of a much larger perspective – namely, what Franklin says himself.

While he may welcome and be pleased with the fund’s short history, he would point out that it is not a complete market cycle; that its upside is limited in certain markets, especially during a bubble; that when the whole market begins to be overvalued, it won’t participate; and that if this continues for some time, it will continue to underperform.

That is because Franklin views his performance based on the research he conducts, adherence to the process, and emotional discipline. He believes in the process, and if he doesn’t perform well, he will have to look back and see if it was because he made mistakes, is the result of bad luck, or some other external factor. The most important idea is to constantly improve and produce salubrious risk-adjusted returns. So far- so good.

At 38%, most of the fund is in Europe; however, 8.7% is from its holding in Clere AG.

Cash has averaged 34% since the inception of the fund, measured on a quarterly basis. It has ranged from 12% to 62%, again measured on a quarterly basis. Cash is about 20% as of mid-December. The fund’s portfolio turnover is 32%/Yr.

Franklin presently avoids investments in China and Russia because of their special risks; however, this view is not permanent. In many cases, he cannot trust that the cash on Chinese balance sheets is really there. Concerning Russia, he does not want to take the appropriation risk at this time. Besides, other potential ideas have more easily defined risks compared to those in China and Russia.

Application of Behavioral Finance

One component of Intrepid’s and Franklin’s investment process is the emphasis on behavioral finance to avoid their own mistakes rather than bet on the emotions of others for some sort of positive event. He says that checking his biases and emotions is a constant, especially before and after taking action. For example, one particular emphasis is determining what could go wrong with a position ex-ante and how he wants to react if in fact something bad happens. This only works with the “known unknowns,” but it is helpful with managing emotions.

Another example of how he and the firm implement behavioral finance includes avoiding sellside research, sometimes entirely, but always after they have formed their own thesis in order to avoid biases. Additionally, trying to speak only with management about objective facts is important because it is easy to be led astray by promotional management.

Also, understanding the human condition to avoid mistakes motivates him and is an evolving process. He says that Charlie Munger’s 25 cognitive biases is as good of a quick summary as anything in the psychological literature about human misjudgment and an even better guide than the traditional concepts written about the subject, for example, the house money effect, hindsight bias, anchoring, etc.)

Neither he nor the firm evaluates markets as many of their competitors do. They try to treat it as Benjamin Graham has done – as a manic-depressive business partner. It is far too easy to get caught up in the vicissitudes of the market if that is the focus rather than on the bottom-up investing that they do themselves.

As someone who applies an awareness of behavioral principles, cognitive biases, human misjudgment, and decision making, Franklin recommends that investors do the same – even the most intelligent of them – by picking up a psychology book, not another investment book. Doing so, he says, may lead them to have better investing results. Human thinking is filled with “psychological hazards and pitfalls” as he calls them. Being aware of our own psychological limits helps us recognize them and thereby evaluate decisions before and after we make them.

Bottom Line

ICMIX offers investors the opportunity to own an all cap international value fund having a distinct strategy for buying undervalued companies throughout the globe. Its process is distinctive, based on principles used for years by the Adviser, and now currently applied as a unique investment product compared to others in its category. Franklin points out that not much money exists from other firms in small cap international value because they may not see these offerings as scalable.

Franklin emphasizes a long-term approach focused on producing superior performance during full market cycles by participating to the extent possible in favorable up markets complemented by caution in overvalued ones. As such, the fund warrants consideration by investors as a promising new offering and additional discussion here.

Franklin’s taking a long-term view when investing in stocks means it could take quite some time for the thesis to play out. Potential investors need to understand that and should be taking the same approach. He adds, however, that sometimes things happen faster or slower than expected. While he can’t say what the future will be, he can discuss what the portfolio looks like today and his thoughts about it.

Does investing in the fund require extraordinary patience? Clients who take a long-term approach, he says, do not feel that they are being patient. The only pressure they would feel, he states, would be self-inflicted, and if they believe in the process, they won’t feel that pressure.

While the portfolio is currently deep value, Franklin says that he isn’t sure that patience needs to be greater than it is for Intrepid’s traditional products. Many managers avoid deep value because it’s not as easy of a sell. While it’s easier to talk about the benefits of investing in a company like Nestle, it’s not as easy for buying a small unknown company in Australia. But this is what opens up opportunity for him, is the right thing, and that over time investors will realize it.

With these ideas in mind, he says that the fund is not right for everyone.

As someone who frequently uses quotations to highlight his quarterly commentaries, Franklin alludes to the Greek Stoic Epictetus (55 A.D. – 135 A.D) who spoke of living life as if “wealth consists not in having great possessions but in having few wants.” If someone agrees, then short term movements in prices are palatable. On the other hand, if one lives like Mae West who said, “I generally avoid temptation unless I can’t resist it,” then a person is probably speculating to earn enough to offset some other financial error, and negative moves in prices will be unbearable.

Those at Intrepid spend time talking to clients, attending conferences, and giving presentations. Education, not promotional management, is their goal. The fund communicates with shareholders through semiannual webinars featuring manager Q&A and detailed quarterly reports focused on their holdings and current thinking. Their website clearly explains the firm’s philosophy, strategies, and risks for each of their funds. Franklin adds, ““We welcome clients and prospects of the Fund wishing to get a better understanding, and who want to get in the weeds with us regarding our thinking, to email or call.” The door is open.

Fund website

Intrepid International

Then Julius Caesar put an end to (almost) all that foolishness. In 46 BCE (they would have called it 708 AUC, “after the founding of Rome”), he stripped the priests of their ability to control the year, aligned the new year with the start of the January 1 consular year and imposed a 12-month, 365-day calendar. That all made 45 BCE a tough year because, to get everything lined up again, he had to add three extra months; an old-style intercalary month at the end of February and two newbies between October and November. (But just once, so don’t get used to it.) Then he announced that all the world had to surrender their native calendars, showing that the power of Rome was so great that even the year bent to its will.

Then Julius Caesar put an end to (almost) all that foolishness. In 46 BCE (they would have called it 708 AUC, “after the founding of Rome”), he stripped the priests of their ability to control the year, aligned the new year with the start of the January 1 consular year and imposed a 12-month, 365-day calendar. That all made 45 BCE a tough year because, to get everything lined up again, he had to add three extra months; an old-style intercalary month at the end of February and two newbies between October and November. (But just once, so don’t get used to it.) Then he announced that all the world had to surrender their native calendars, showing that the power of Rome was so great that even the year bent to its will.

What’s the Trapezoid story? Leigh Walzer has over 25 years of experience in the investment management industry as a portfolio manager and investment analyst. He’s worked with and for some frighteningly good folks. He holds an A.B. in Statistics from Princeton University and an M.B.A. from Harvard University. Leigh is the CEO and founder of Trapezoid, LLC, as well as the creator of the Orthogonal Attribution Engine. The Orthogonal Attribution Engine isolates the skill delivered by fund managers in excess of what is available through investable passive alternatives and other indices. The system aspires to, and already shows encouraging signs of, a fair degree of predictive validity.

What’s the Trapezoid story? Leigh Walzer has over 25 years of experience in the investment management industry as a portfolio manager and investment analyst. He’s worked with and for some frighteningly good folks. He holds an A.B. in Statistics from Princeton University and an M.B.A. from Harvard University. Leigh is the CEO and founder of Trapezoid, LLC, as well as the creator of the Orthogonal Attribution Engine. The Orthogonal Attribution Engine isolates the skill delivered by fund managers in excess of what is available through investable passive alternatives and other indices. The system aspires to, and already shows encouraging signs of, a fair degree of predictive validity.