An impending civil war in the US. A planet on fire. The worst drought in 1500 years. The prospect of Putin using nuclear wars in Europe. A market decline that might be accelerating rather than slowing. Inflation at 40-year highs. Crazy people storming the Capitol. Voter restrictions. Politicians increasingly willing to assert control over women’s lives.  We are afraid.

We are afraid.

Fear is many things, depending on the circumstances. It can be appropriate, rational, essential, energizing, and productive. Fear, as an evolutionary response, works really well to help us address threats that are (1) immediate and (2) physical. Snarling dog running in your direction? Be afraid! Be very afraid … and vault effortlessly over that 10’ fence.

But fear can also be the opposite: inappropriate, irrational, unneeded, exhausting, paralyzing. Fear, as a social response, works really poorly to help us address threats that are (1) ongoing and (2) psychological.

Here are three things you need to know.

1. Your fears are invented for the profit of others

You’ve acquired your fears as the result of a three-step process. (1) Things happened. (2) Someone decided that they could profit if you experienced the thing as a terrifying threat. (3) Those terrifying visions were pushed to you, and you couldn’t look away.

Things are forever happening, the question is how we frame them. That is, what’s the story you learn to tell yourself about the event? Are tens of thousands of people – mostly parents hauling small children – attempting to cross the southern US border a cause for hysteria (“an invasion” or “a crisis at the border”), a cause of compassion (what would it take for you to decide to walk two toddlers for a hundred miles?) or a call to reassess US international and economic policy in the Americas? That’s one event that can be framed three different ways, and those different frames can arouse anxiety, paralyze thought, encourage rage … or the opposite.

Sadly, fear-mongering is highly profitable. Tens of thousands of websites or dozens of “news” outlets need you to show up, preferably dozens of times a day. The best way to do that is to energize your obsessive fears. Eric Deggans, media critic for National Public Relations:

Instead of informing audiences, many of the fastest-growing news programs and media platforms are playing on old prejudices and deep rooted fears to compete for increasingly narrow audiences. Using the same tactics once employed to mobilize political parties, they send fans coded messages and demonize opposing groups as their audience share soars and website traffic ticks up. (Race Baiter: How the Media Wields Dangerous Words to Divide a Nation, 2012)

Jeffrey McCall, professor of communication at DePauw University:

Americans are fearful in large part because too many establishment media provide a constant drumbeat of frightful shadows that send news consumers looking for places to hide their heads. Stories of woe permeate today’s media messaging, seldom with nuanced reporting that puts threats in proper context.

The news agenda on a micro level covers a variety of dreadful events and stories, but the macro message boils down to one headline: “Be Afraid.”

Propagandists work under the assumption that people eventually believe what they hear most often. The constant hyping of a culture of fear has rhetorically scared otherwise reasonable Americans into irrational emotions and behaviors. (Media spread fear, Americans listen, 5/30/21)

Fear is an adaptive evolutionary response designed to keep us safe. The problem is that it’s possible for those seeking to lead us to manufacture fear; that is, to create the crises in which propaganda flourishes. Arash Javanbakht, Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, Wayne State University argues that

Fear is a very strong tool that can blur humans’ logic and change their behavior.

Politicians and the media very often use fear to circumvent our logic. I always say the U.S. media are disaster pornographers – they work too much on triggering their audiences’ emotions. They are kind of political reality shows, surprising to many from outside the U.S.

When one person kills a few others in a city of millions, which is of course a tragedy, major networks’ coverage could lead one to perceive the whole city is under siege and unsafe. If one undocumented illegal immigrant murders a U.S. citizen, some politicians use fear with the hope that few will ask: “This is terrible, but how many people were murdered in this country by U.S. citizens just today?” Or: “I know several murders happen every week in this town, but why am I so scared now that this one is being showcased by the media?”

We do not ask these questions, because fear bypasses logic. (“The politics of fear: How it manipulates us to tribalism,”7/17/19)

2. Chronic fear is a disaster for your health

When we are afraid, our brains take dramatic actions to ensure our survival. Much of our decision-making is usurped by the amygdala, two almond-shaped organs located deep in our brains. The amygdala is responsible for fast, emotion-driven reactions designed to keep us alive. It triggers massive releases of adrenaline, cortisol, and stored sugars; our breathing speeds up, and our blood begins carrying more oxygen; our muscles tense, body temperature spikes, and blood flow is redirected away from non-essential organs (your stomach and salivary glands, as examples, which leads to the “rock in my stomach” feeling and a dry mouth).

The “fight” part of the fight, flight, or freeze reaction means we’re not only frightened but we’re also mad. Jacob Hess, in a singularly well-written article, warns that “media glorifies outrage in headlines like ‘If you’re not angry, you’re not paying attention.’ But what we should be reporting on and talking about more is what all this chronic anger is doing to all of us” (What chronic anger is doing to us, 9/16/2022).

The problem is that this fight, flight, or freeze reaction is only supposed to be triggered rarely, briefly, and in the face of imminent threats to survival. According to Harvard Health (2020), chronic activation of this survival mechanism is commonplace and damaging to our physical and mental wellness.

When there is a repeated and prolonged sense of danger, we place ourselves at risk of developing chronic anxiety, depression, immune system failures, and wretched sleep.

Also, weight gain. (Nuts.)

In short, your favorite politicians, favorite talking heads – no, I’m not going to name them because that would only feed your anger – and favorite feeds … are killing you.

3. Chronic fear stops you from solving the problem you fear.

Here’s the good news: the world is always teetering on the brink of destruction!

No one captured that insight quite like Tommie Lee Jones in Men in Black (1997)

We nearly had a nuclear war about 39 years ago because of a computer glitch, didya know? At a moment of intense international tension in the wake of the Soviet destruction of Korean Air Lines flight 007, their missile defense radars reported an incoming US first strike. The rules were clear: the watch officer had to immediately sound an alarm and escalate word of the attack to senior leadership. (He didn’t. Thank you, friend Petrov.)

The American democracy has nearly collapsed into anarchy about once a generation since its founding; it went far enough that, against a background of armed militias and political hysteria, in the summer of 1933, there was actually a coup attempt organized by America’s wealthiest investors against President Roosevelt. One of the most influential books I’ve ever read was a textbook from my undergrad political science sciences, The Irony of Democracy (17th ed., 2015).

If the survival of the US system depended on an active, informed and enlightened citizenry, then democracy in the US would have disappeared long ago, for the masses normally are apathetic and ill-informed about politics and public policy, and they exhibit a surprisingly weak commitment to … individual dignity, equality of opportunity, the right to dissent, freedom of speech and press, religious toleration and due process of law.

Democratic values thrive best when the masses are absorbed in the problems of everyday life and involved in … work, family, neighborhood, trade union, hobby, religion, group recreation, and other activity.

To be clear: that’s not their description of 21st-century America. That’s the reading of nearly 250 years of American history. “The irony of democracy” is that it survives only when most people leave it alone.

And yet, despite all of that, we’re still here. More importantly: we’re here, and things are, generation by generation, getting better. Politicians hype crime in the cities without acknowledging that violent crime has fallen to its lowest levels in a century. Childhood poverty has dropped dramatically in 25 years. Poverty and hunger have fallen on every continent. There’s an increasingly credible case for climate optimism, even in the face of still-mounting threats. More people in more countries live under at least nominal democracies than ever, and more women in more countries are receiving the benefits of more education than ever.

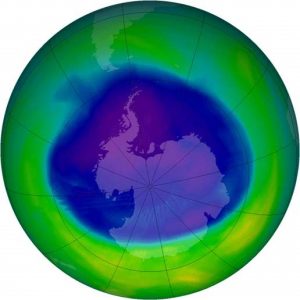

The poster child for the possibility of meaningful progress is the storied ozone hole.

Did you know that the earth is healing itself, and we’re helping? In September 2022, NASA scientists reported a major milestone: the ozone-destroying gases in our upper atmosphere have declined by more than half since the problem was first discovered. It is now on track to be completely healed over most of the planet by the 2030s and over the poles by the 2050s.

Did you know that the earth is healing itself, and we’re helping? In September 2022, NASA scientists reported a major milestone: the ozone-destroying gases in our upper atmosphere have declined by more than half since the problem was first discovered. It is now on track to be completely healed over most of the planet by the 2030s and over the poles by the 2050s.

The ozone shield protects all life on the planet – you, me, Elon Musk – from lethal radiation. If there were no ozone in the atmosphere, according to NASA, “the Sun’s intense UV rays would sterilize the Earth’s surface.” The hole we punched in it through the release of a class of chemicals called CFCs, mostly used as propellants in spray cans and in refrigerators and air conditioners, was large, growing, and linked to both cancer and blindness.

And then a strange thing happened: people decided to recognize and fix the problem. Politicians talked with scientists, diplomats talked with one another, countries wrote laws and signed treaties, reporters explained to people what was happening… and we fixed it. (Mostly, so far.)

We noted, three looooooong years ago, that optimists, who assume things will work out, tend to see more paths forward, more options worth considering, than pessimists (often dubbing themselves “realists”) who know that it’s eternally time to duck-and-cover.

The word “optimism” entered the English language (1759, in French 1737) several generations before pessimism (1794) did.

The psychological research on the effects of optimism is stunning. The champion of such research is Dr. Martin E.P. Seligman, a Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and Director of their Positive Psychology Center. He focuses on notions like “learned helplessness” and has racked up rather more than 325 journal articles and books. His most widely-cited work, Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life (Vintage Books, 2006), has been cited by other scholars on 11,540 occasions. In it, he argues:

The defining characteristic of pessimists is that they tend to believe bad events will last a long time, will undermine everything they do, and are their own fault. The optimists, who are confronted with the same hard knocks of this world, think about misfortune in the opposite way. They tend to believe that defeat is just a temporary setback, that its causes are confined to this one case. Optimists believe that defeat is not their own fault: Circumstances, bad luck, or other people brought it about. Such people are unfazed by defeat. Confronted by a bad situation, they perceive it as a challenge and try harder.

These two habits of thinking about causes have consequences. Literally hundreds of studies show that pessimists give up more easily and get depressed more often. These experiments also show that optimists do much better in school and college, at work and on the playing field. They regularly exceed the predictions of aptitude tests. When optimists run for office, they are more apt to be elected than pessimists are. Their health is unusually good. They age well, much freer than most of us from the usual physical ills of middle age. Evidence suggests they may even live longer.

We are fixing a freakin’ 10 million square mile hole in the ozone layer! What else could we do if we shifted from making enemies to finding partners?

For readers worried about the climate (which should be every single one of you):

We could, in relatively short order, reverse the melting of the polar ice caps. As in, stop the melting then reverse it within a matter of years for $11 billion a year, the same amount we spend on litter clean-up in the US. The plan would be to inject aerosols high above the poles, which would increase the ice crystals in the atmosphere and would reflect more heat back into space. It would be a Band-Aid, surely, but one which might buy us time to make more systematic change.

Individually, get involved locally. Don’t try to fix the world. Try to get your city government to change the building code to encourage green roofs, support pocket parks, and plant city trees. Heck, for $1, you can get a tree planted yourself.

For readers worried about political dysfunction:

Get involved locally. I know you don’t want to encourage strangers to vote, plant yard signs, make calls, volunteer hours, and suffer similar indignities. And yet, that’s where change happens. In 2020, the race for a seat in the US House of Representatives for my district in eastern Iowa was decided by seven (7!) votes.

About half of the local elections here are uncontested: two candidates for the two open seats on a county board, as an example. So here’s a scary thought: become one of those two. You’re sensible, insightful, and temperate. You could make a difference in your city … which could make a difference in your state … which might, just maybe, change America.

For readers worried about the direction of the Supreme Court:

Encourage moderation in Congress. The Court mostly steps into vacuums, creating rules where Congress hasn’t. And Congress hasn’t acted because its members are increasingly rewarded for immoderation and intransigence. Perhaps talking with your member of Congress when they hold their district office hours? Perhaps voting for the most sensible person, rather than the one with the right color affiliation. Perhaps voting??? The record level of participation was set in the 2018 mid-term elections: 50.1%. The typical level would be 40%.

So, vote, don’t just plan to vote. Take a friend. Do good for yourself.

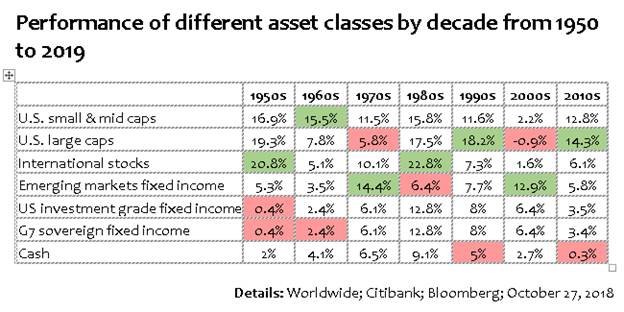

For readers worried about another lost decade in the stock market:

It is entirely possible that US large cap stocks will hover, in 2032, right about where they are now. We can identify at least four lost decades since 1870 … at least measured by that standard. But there have been no decades since the 1950s where at least one major asset class didn’t post double-digit returns.

That excludes asset classes such as EM equities which weren’t investable over the entire period.

If your strategy is to stick blindly to the Church of What Worked Recently, you’re likely in trouble. If you recognize that undervalued assets produce oversized returns in the long run and you’re prudent in the short run, you’ll be fine.

The next decade will be the worst of times and the best of times. You get to choose which by deciding how you think about (or frame) events, where you look, and how effectively you act.

In reality, it doesn’t get any better than that.