Readers know that I long ago concluded that active management rarely adds value to an investor’s portfolio. There are too many managers fighting over the same stocks. Very few of them have a meaningful Edge over the others. Most of those who add some value rarely add enough to overcome the drag imposed by their expenses and higher tax burden. Some few add serious value, but they are almost impossible to reliably identify in advance.

That said, I am about to commit two heresies in one column: I will suggest that you consider investing internationally, and if you choose to do so, I will suggest that you consider entrusting your money to an experienced active manager. (I know. It surprised me, too.)

International equities and a good question:

“Why do you still invest in the international markets (stocks outside the USA)?” I was asked by a highly astute head of a large family office at a recent lunch. The question was in response to my description of an asset allocation portfolio that invested in U.S., International, and Emerging Markets Stocks, along with Bonds and REITs.

The last decade has not been kind to foreign stocks:

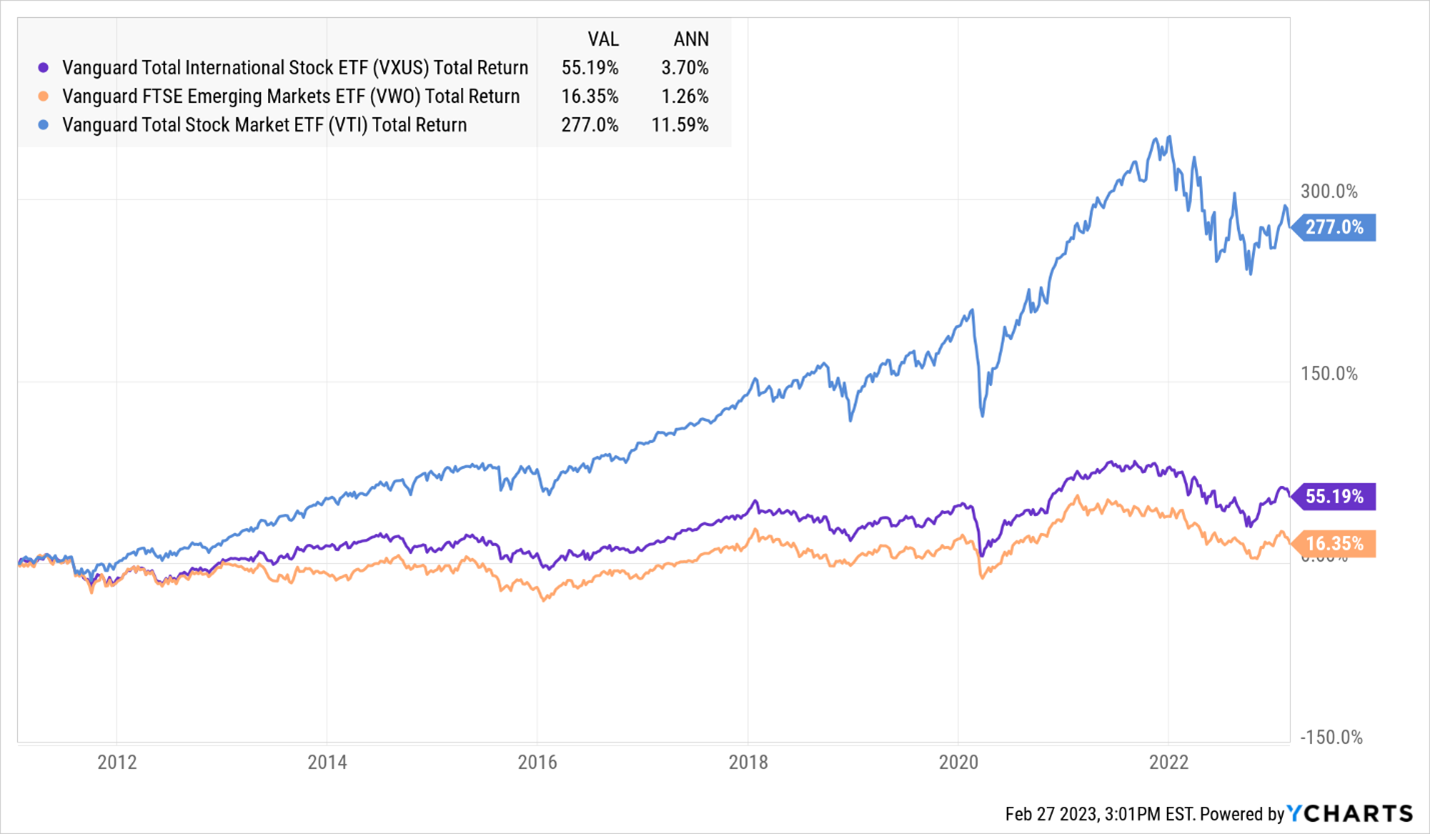

It takes one look at the following chart to determine the basis for his question. From the start of 2009 to Feb-end 2023, U.S. equities measured by the returns of the Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI) enjoyed a total return of 277%, while the Vanguard International Developed Markets (VXUS) returned 55%, and Vanguard Emerging Markets (VWO) only 16% (or an annualized return of 1%, just 1% a year … a return I would have beaten with a carefully timed investment in a lemonade stand!!). Since that includes dividends, the price returns are even less.

His arrow, therefore, was aimed at the practice of the Vanguard idea of low-cost, passive, broad-based investing – except this time in foreign and emerging markets stocks. While in the decades past, it was considered acceptable to say some nonsense like “the diversification benefits of investing in a major asset class uncorrelated to U.S. equities,” anyone with money in these foreign markets knows better. It is now clear that the idea of passive investing that works so well in the United States has been a disaster when looking at foreign equity assets.

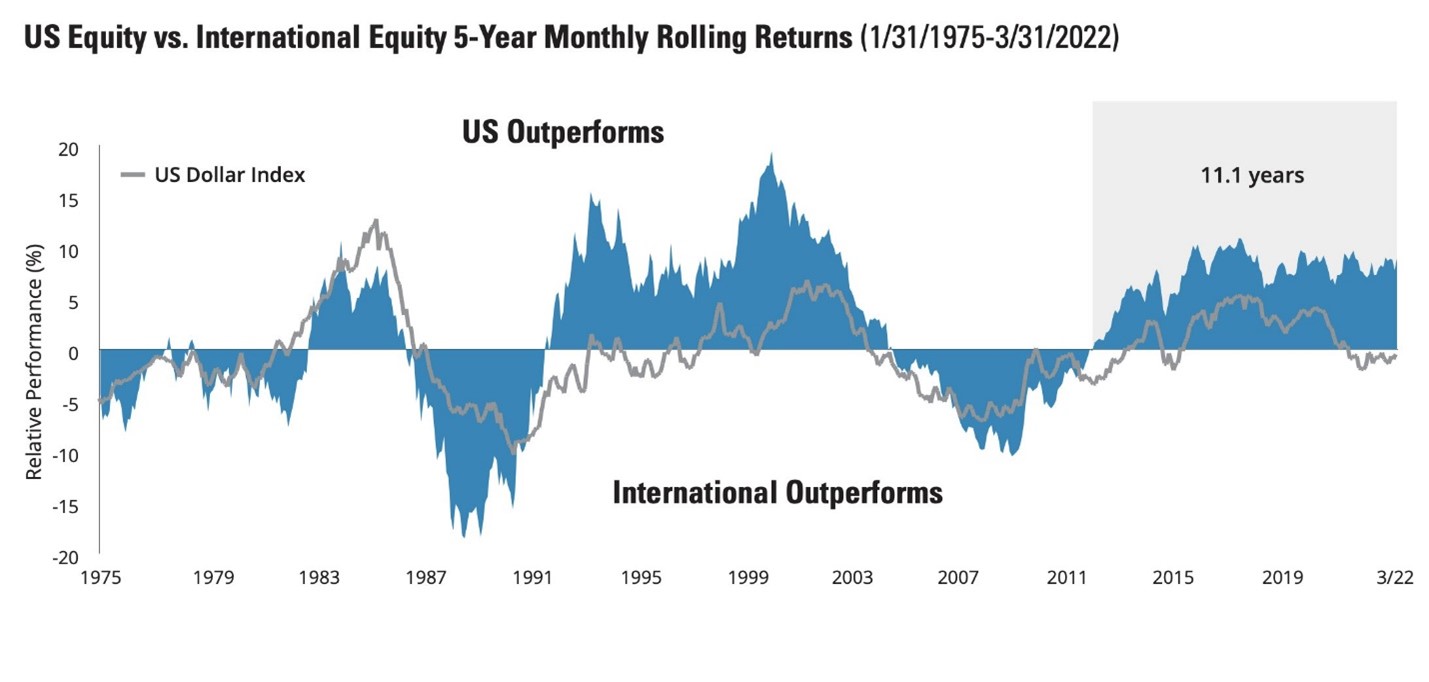

That decade-long lag raises two important perspectives. First, because valuations globally are lower than valuations locally, many capital models project a decade of international outperformance relative to U.S. stocks. Charles Schwab’s capital model, for instance, projects a 150 bps advantage for international large caps over domestic ones with returns of 7.6% versus 6.1% annually. Second, the mere existence of a period of U.S. outperformance is not remarkable. Historically, U.S. and international stocks quite typically trade periods of extended dominance.

Source: The Onveston Letter (2023) via Alex MacKinnon, Twitter

We might be at the point of such a trade.

Passive diversification has not worked

For the well-meaning U.S. investor trying to behave virtuously by spreading her bets in a systematic manner across the world, the reality is humbling. Across any recent time period, international stocks have not zigged when the U.S. stocks zagged, therefore, providing no particular diversification benefit. There are no large swaths of foreign markets where capitalism works better than the U.S., where corporate management is better, where earnings are higher or smoother, and where the currency is consistently more stable than the U.S. dollar because of institutional strengths of the regulatory and judicial bodies or their prudential Central bank policies. It took some of us a few decades to learn this, but now we know.

When does passive international investing work?

Home Sweet Home Investing

The disdain for investing in “foreign” markets – even if the foreign market in question is the US – is described as “home bias,” and it is nearly universal. Home bias in India is nearly 100%, according to Morningstar. An analysis of equity holdings in mutual funds from 26 different countries shows that equity home bias is universal. All 26 exhibit domestic bias: Greece, for example, has the highest percentage of average mutual fund holdings in its domestic market (93.5%), as compared to its mean world market capitalization weight of 0.46%, a 200:1 overweight. In Austria, the overweight was 75:1; in Mexico, 30:1. Chan, et al, “What determines the domestic bias and foreign bias? Evidence from mutual fund equity allocations worldwide. Journal of Finance (2005)

To be fair, there are times when passive investing in foreign stocks does work well:

- When you get lucky – For example, if you picked India, rather than Brazil or China.

- When foreign currencies rise in value compared to the U.S. Dollars. Usually, during these periods, commodities tend to go up in price as well. Foreign equity indices in U.K. and Australia are heavily made up of commodity companies. Thus, a boost from both the F.X. and Commodities leads to foreign stocks doing well.

- After a large crash in risk assets, foreign stocks, which generally decline more than U.S. stocks because of their illiquidity, usually see a big rebound when the markets settle down.

Predicting the future (India over China), or the direction of F.X. and commodity prices should not be a requirement for investing. That belongs more in the category of tactical rather than strategic investing. Buying stocks after a crash is always a good idea, no matter what asset class, but how many will?

We can keep making excuses for the U.S. equity outperformance – growth stocks, tech stocks, quantitative easing, stimulus, buyback, etc. But at some point, we must face the music. Large US companies seem to be mostly a fine way to gain exposure to international markets. The need and rationale for passive investing abroad is the weakest it’s been in a while, and there is no reason to see that change. True, valuations abroad are cheap and have been seen so for a long period. We only understand the reasons now. Those markets never deserved a high valuation. U.S. stocks can come down too, but for this article, we are discussing International equities.

Active Investing over Passive outside the USA

No international large cap index fund has won in the long-term

We searched the MFO Premium database for the 20-year returns of all international large cap funds and ETFs. No diversified passive fund outperformed its peer group average and only one matched the group average. Of 71 qualifying funds, no index fund made the top 50%. The one exception: MSCI Canada ETF, a non-diversified fund that badly trailed the only actively managed Canada fund, Fidelity Canada, on the list

At MFO, we have the privilege of meeting lots of Active Fund managers focusing on international markets. To their credit, many of them have done much better than the passive indices they track. We did a piece on Emerging Markets Players that covered some of the well-run Active EM funds from Seafarer, Rondure, Causeway, William Blair, Pzena, and Harding Loevner. Fortified with the knowledge acquired in talking to many of these managers and reading their letters, my response to the proposed question of “why international markets” was that the case for International Investing now rests on the shoulders of Active Management. It is better to adapt and choose Active Managers rather than completely exit international investing. There are opportunities everywhere and we need to learn how to capture them.

Good Active Investing is also about what not to buy

Major Holders of Adani Enterprises

Of the 20 largest holders of Adani Enterprises, the company’s flagship entity, 17 are index funds, two are active funds for Indian investors – Kotak Balanced and SBI Balanced, one is a global fund – GS EM Core – not available to US investors. None of the 20 largest holders is an actively managed US fund or ETF. Per Morningstar.com

Good active investing is as much about what not to hold as it is about what to hold. Take the case of the various Adani companies based in India. As of Aug 2022 prospectus, the MSCI India ETF owned Adani Transmission ($61mm), Adani Total Gas ($58mm), Adani Green Energy ($43mm), Adani Power ($17mm), Adani Enterprises ($51mm), and Adani Ports ($25mm). That’s $255mm out of an AUM of $4.1 Billion, or roughly 6.2% of the fund. When the US-based short seller, Hindenburg Research, put out a negative thesis on Adani, many of these stocks lost more than 50-70% in less than a month. Some of the Adani stocks have not even opened for trading since the day after the research note.

Here’s the interesting part – every smart fund manager focused on India had long avoided all Adani stocks. One understood Mr. Gautam Adani’s special place in Indian business because of his long-standing friendship with the current Prime Minister, and therefore, did not short the companies. But most Indian fund managers worth their salt were not long the stocks either. The bag holders were local retail investors chasing momentum and local and global ETF investors. MSCI India recently reduced Adani stock weights by adjusting down its free float, and several ESG funds reduced their holdings after “further analysis” – also known as buying puts after the market has crashed.

How my personal portfolio has evolved:

My own portfolio of non-US stock investments has evolved over time. I can attest that I currently do not own any International or Emerging Passive ETFs. I own an actively managed Private Equity fund in India, where I have been an investor for over 15 years. I own a Hedge fund, also focused on India. Both these funds are run by friends, making them much easier to  be invested in. I grew up with these people. In public markets, I own two actively managed equity mutual funds run by Seafarer – the Emerging Market fund (Andrew Foster) and the International Value Fund (Paul Espinosa). I might tactically purchase specific country or style ETFs but would be hard-pressed to strategically and long-term invest in foreign markets anymore using passive investing.

be invested in. I grew up with these people. In public markets, I own two actively managed equity mutual funds run by Seafarer – the Emerging Market fund (Andrew Foster) and the International Value Fund (Paul Espinosa). I might tactically purchase specific country or style ETFs but would be hard-pressed to strategically and long-term invest in foreign markets anymore using passive investing.

In conclusion:

- International investing is not for everyone. Most of us will lose patience along the way.

- If you are going to go down the road of investing in foreign securities, choose Active over Passive. Passive indices are constructed poorly overseas. What’s worked in the U.S. does not work abroad.

- Proper Active needs talent and skill.

- Even more importantly, proper Active needs <<<TIME>>>

- When we invest in Mutual Funds pursuing International investing, especially those with a Value bent, we need to give them a lot of time – almost as if it was an illiquid private equity investment.

- It helps to invest with managers with significant battle experience and a significant amount of their own assets in the fund.