Welcome to July, dear friends.

It’s summertime, an especially blessed and cursed interval for those of us who teach. On the one hand, we’re mostly freed from the day-to-day obligation to be in the classroom. Some of us write, some travel, some joke about “going topless at the beach” which translates to leaving their masks at home, some undertake “such other duties as may from time to time be assigned” by our colleges. On the other hand, we hear the clock ticking. All year long, as we try to face down a stack of 32 variably literate essays at 11 p.m. Sunday night, we think “if I can just make it to summer, I’ll recharge and it’ll be great!” About the first thing we notice when summer does arrive, is that summer is almost spent and we’re already receiving anguished pleas from students who gotta gotta gotta get into fall courses that (a) are already overfilled and (b) I don’t want to think about. Just yet.

And so, I’ll think about the errant silliness of supposed adults instead!

Investors are being fools. It’s a good time for it.

Want a snapshot of foolishness: someone has made, and intends to auction, a non-fungible token made from his own … uh, fecal matter. It’s unlikely to top the $69 million on a Beeple NFT (nope, no idea either) back in March, but it might certainly go for millions.

Of course, they’ve been assisted in their foolishness. FINRA announced its largest ever financial penalty, around $70 million, levied against Robinhood. FINRA found in its investigation that,

despite Robinhood’s self-described mission to “de-mystify finance for all,” during certain periods since September 2016, the firm has negligently communicated false and misleading information to its customers. The false and misleading information concerned a variety of critical issues, including whether customers could place trades on margin, how much cash was in customers’ accounts, how much buying power or “negative buying power” customers had, the risk of loss customers faced in certain options transactions, and whether customers faced margin calls.

Additionally, between January 2018 and December 2020, Robinhood failed to report to FINRA tens of thousands of written customer complaints that it was required to report.

None of which seems likely to faze the company. Assets under custody (basically, the size of its users’ accounts) grew from $19 billion in March 2020 to $80 billion in March 2021. The number of live user accounts grew from 7.2 million to 18 million and the firm is preparing to offer an IPO. They estimate their own value at $40 billion.

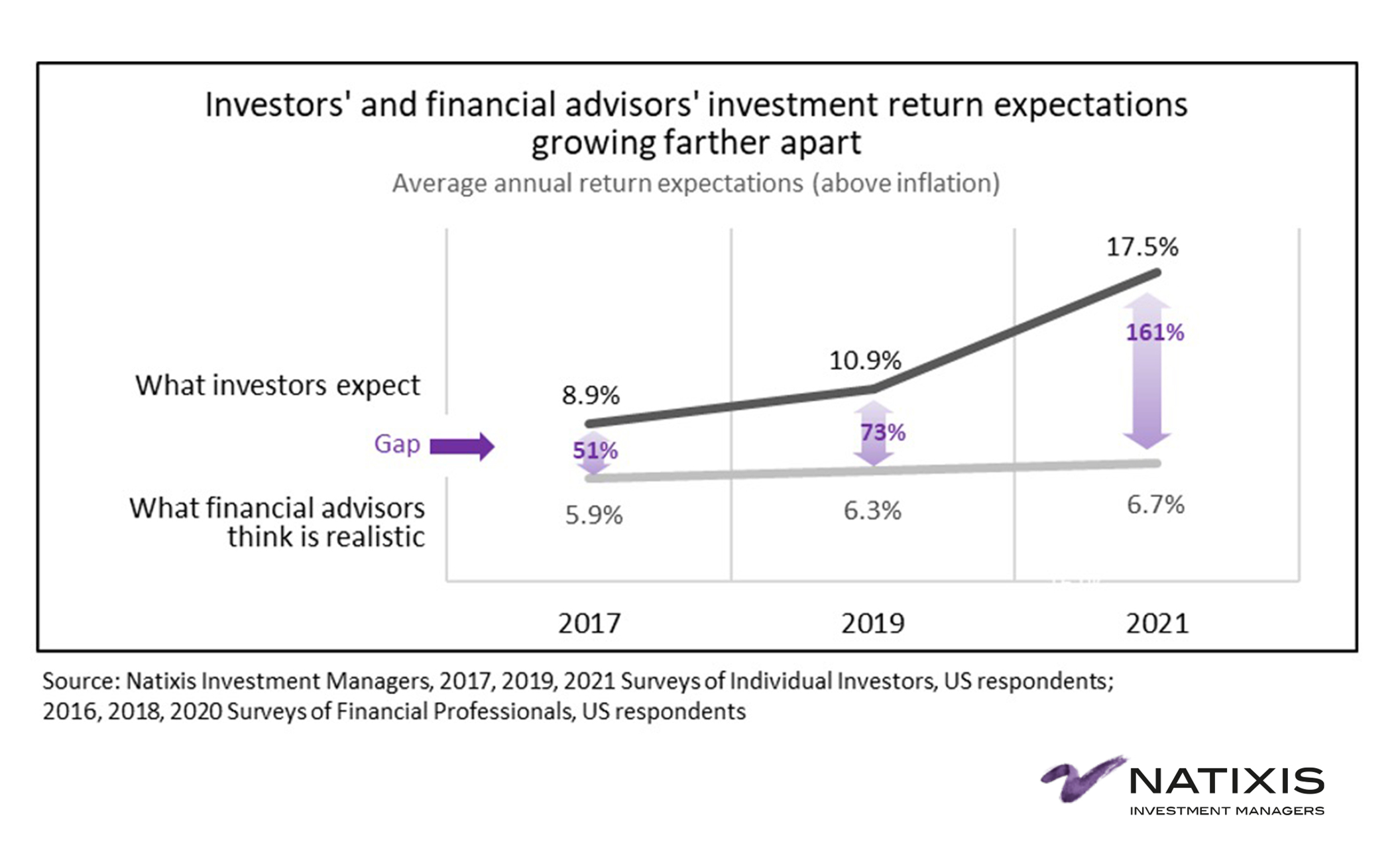

Against the backdrop of last year’s frenzy, a 2021 Natixis survey of relatively sophisticated investors shows that American investors now expect 17.5% annualized real returns on stock investments.

Nonetheless, if you’re going to be a fool, this is about as good a time as any.

Investors have a larger-than-average cash cushion.

We love spending our money, often bucketloads at a time. For better and worse, the Covid pandemic slammed the brakes on many types of consumer spending. In consequence, people left money pile up in the bank.

Since the onset of the coronavirus outbreak, bank deposits of households and companies across the world have swelled to levels never seen before. This situation stands in stark contrast to the similarly pronounced global financial crisis (GFC) between 2007 and 2009 when deposit levels at banks declined amidst a debilitating global credit crunch. But today, as the pandemic continues to shutter businesses and restrict households, deposits at banks continue to balloon—and perhaps most concerning of all is that this expansion shows no signs of slowing down.

“Any way you look at it, this growth has been absolutely extraordinary,” Brian Foran, an analyst at Autonomous Research, told CNBC last July. “Banks are flooded with cash; they’re like Scrooge McDuck swimming in money.” But if deposits had reached unprecedented levels back then, it has only become even more concerning since then.

According to the Quarterly Banking Profile (QBP), which provides a comprehensive summary of financial results for all US institutions insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, deposits grew by $635.2 billion during the first quarter of 2021 to reach a whopping $18.5 trillion. This is 3.6 percent higher than last year’s fourth quarter and thus underlines the startling pace at which deposits have grown over the last few quarters. (Joseph Moss, International Banker, 6/28/2021).

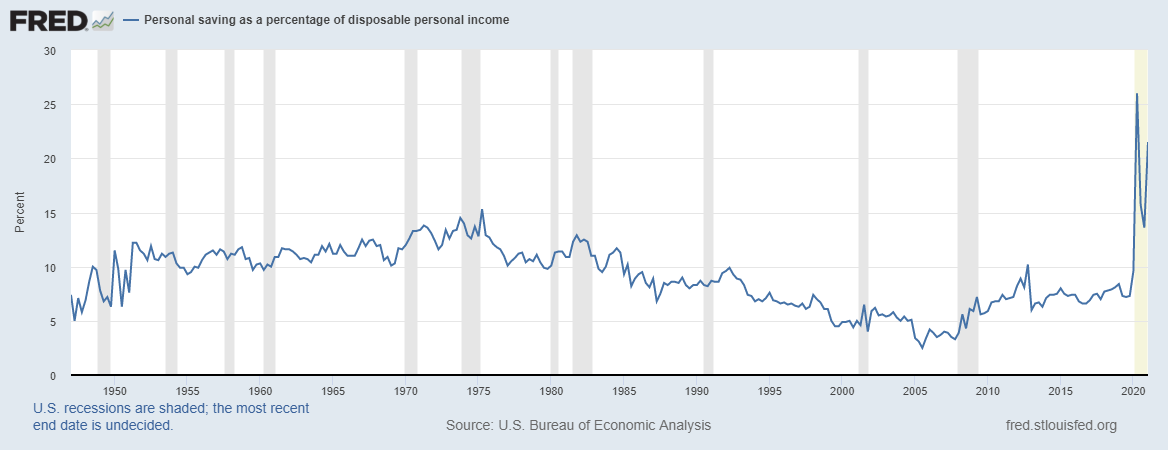

A quick check of Fed data (6/30/2021) shows an enormous spike in personal savings as a percentage of our income.

Many people have enough surplus cash that losing a chunk of it won’t be devastating. (And many of the folks living paycheck-to-paycheck have marginal exposure to the stock market.) Merryn Somerset, writing in the Financial Times, wryly notes that this surplus might inconvenience any number of marketing departments:

The upshot of this is that one of the industry’s main marketing strategies has to be the constant release of the kind of statistics that keep you in a state of perpetual anxiety about whether you have or have not saved enough. (“Time for an investment step change,” FT.com, 6/10/2021)

The most speculative investments are correcting.

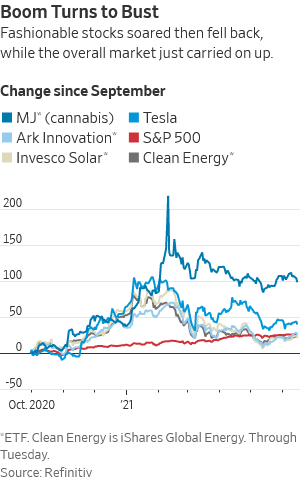

James Mackintosh, writing in the Wall Street Journal, notes that we might have passed peak silliness for a number of … investment-like objects. He illustrates the possibility with this graphic.

The most speculative sectors don’t threaten the larger markets, at least not in the way that the bursting of the dot.com bubble in 2000 did. James Mackintosh, writing in the Wall Street Journal, reflects on the fact that the price of … oh, marijuana or marijuana stocks really doesn’t mean all that much to us.

But the plunge of share prices in clean energy, electric cars, and cannabis, and even the halving of bitcoin, puts much less of a dent in the wallets of consumers than the dot-com bust did because the bubble is less widespread. Nasdaq’s bubble gave it a value of about half that of the S&P at its 2000 peak, while even with Tesla, the frothy sectors of the past nine months are a fraction of that.

The boom-bust parts of the market also raised and spent less money than the dot-coms, and employ fewer people. If businesses fail as shares deflate they are likely to have less economic impact. Fewer large companies are investing in an imaginary “new economy,” and where they are investing, as with the shift to electric cars, they will probably continue for other reasons, even as shareholders pull back. (“Tesla and Other Bubble Stocks Have Deflated Just Like 2000,” WSJ.com, 6/17/2021)

At the same time that investors are pouring money into equities (US equity funds recorded $189 billion in inflows since February), they’re also buying record numbers of hedges in the options market.

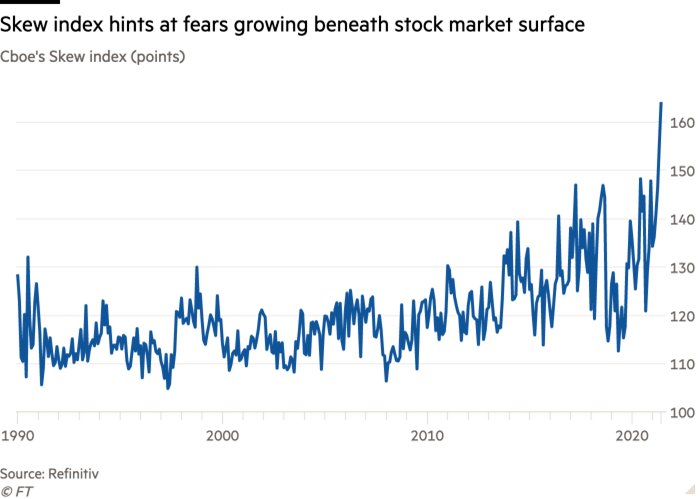

the Skew index — which measures the difference between the cost of derivatives that protect against big market drops on one side, and the right to benefit from a rally on the other — has hit record heights. The Skew gauge rises when fear outpaces greed, so the widening divergence indicates how worries are bubbling up beneath the seemingly placid surface of the stock market.

The Skew Index is compiled by the big Chicago-based options exchange Cboe and is constructed to typically range between 100 to 150 points, where a value of 100 signals that stock market movements are expected to be roughly normal, and higher readings indicate that investors are paying up to hedge themselves against crashes. The index has mostly drifted upwards over the past decade but has climbed particularly sharply over the past month as the rising demand for protection has swamped the fading willingness of other investors to sell it. That lifted the index to a record 170.5 points last week, according to Refinitiv data. (Robin Wigglesworth in Oslo and Michael Mackenzie, “Record Skew index shows nagging investor nerves on US stocks rally,” FT.com, 7/1/2021)

Here’s the picture of it …

Here’s the summary: people have money, they’ve bought insurance and their foolishness is unlikely to hurt the rest of us. So, let the kids have their fun.

Here’s the summary: people have money, they’ve bought insurance and their foolishness is unlikely to hurt the rest of us. So, let the kids have their fun.

An unlikely champion of this view is Morningstar’s John Rekenthaler, not the sort of guy who’d ever be cast as one of the carefree travelers in any remake of Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure (“This should be most triumphant, dude.”) In reviewing many of the same arguments we just did, Mr. Rekenthaler comes away with a distinct “it’s summer … meh” conclusion.

Looking Forward

My take:

1) Some investments undoubtedly are frothy. Morningstar calculates that the average stock in ARK Innovation’s portfolio trades at 106 times its trailing 12-month earnings. That is pricey by any standard.

2) However, given the relatively modest level of consumer debt, shareholders should be able to withstand reasonably large investment losses.

3) They also are protected by the $46 trillion that they hold in mutual fund shares and bank deposits.

In summary, if the general economy remains solid–all bets are off during recessions–everyday investors should be relatively immune to a sell-off in speculative investments, should that event occur. I do not believe that such damage would spread. (“Investing During an Era of Speculation,” 6/28/2021).

Even the venerable Benjamin Graham seemed to be willing to grant that speculating is probably stupid but it isn’t necessarily fatal. Jason Zweig, who prepared the 2006 annotated release of Graham’s The Intelligent Investor (1949) shares his, and Graham’s, take on the activity:

Whenever you buy any financial asset because you have a hunch or just for kicks, or because somebody famous is hyping the heck out of it or everybody else seems to be buying it too, you aren’t investing.

In the book, after which this column is named, Graham said, “Outright speculation is neither illegal, immoral, nor (for most people) fattening to the pocketbook.”

However, he warned, it creates three dangers: “(1) speculating when you think you are investing; (2) speculating seriously instead of as a pastime, when you lack proper knowledge and skill for it; and (3) risking more money in speculation than you can afford to lose.” (Investor, Trader, Speculator: Which One Are You?, 6/18/2021)

None of which justifies any of you joining in the silliness. The US markets remain at record valuations and much of its advance is driven by a touching faith in the federal government: faith that the Biden administration will spend trillions and faith that the Fed won’t be touching that punchbowl – except perhaps to spike it with a bit of rum – at any time in the next couple years.

For those committing new money to the market regardless (and consistent, disciplined investing is a key to success), the recommendations from the ultra-skeptical folks at GMO make considerable sense. Peter Chiappinelli, a member of their Asset Allocation Team comments:

It gives us no pleasure to remind clients that U.S. stocks’ valuations, by almost any measure we can come up with — backward or forward looking —are at levels that concern us … we absolutely concede that somewhere in the Global Growth basket sits “the next Amazon.” Unfortunately, they’re ALL being priced that way, and that is a bridge too far.

We also remind ourselves that during the month of May, the S&P 500’s real earnings yield (the inverse of P/E minus inflation) dipped into negative territory, the lowest in 40 years. Even at the height of the tech bubble mania, this scary event did not occur.

Combine that sober statistic with the negative real yields being offered by sovereign bonds, and you may come to see why we are loathe to recommend a traditional 60/40 mix. There will come a day when global equities and government bonds are fairly valued and should deliver a “normal” real rate of return. Today, however, is not that day.

But May’s forecast is not all doom and gloom, in fact far from it. Emerging Markets Value, which has rallied strongly in the past year, with the MSCI EM Value index up 49%, is still priced to deliver quite decent relative and absolute returns. Japan small value stocks are also quite attractive.

Further, the valuation spread between global Value and Growth remains at some of the widest levels we have seen in our working careers, and there are all sorts of interesting ways to exploit this dislocation. Importantly, valuation spreads across asset classes more broadly in rates and FX and commodities, represent huge opportunities in non-traditional long/short space.

In a global Growth bubble, we are advising clients to do three things: exploit the bubble (via equity long/short), avoid the bubble (via alts), and concentrate assets where the bubble ain’t (EM Value, Japan small Value, Cyclicals, and Quality).

Our recent profiles have been highlighting folks who share many of those same conclusions: value has value, quality is quality. But quality remains at its cheapest, relative to the broad market, in a generation. Brian Sozzi writes,

Quality is on sale in the stock market.

Higher quality stocks are trading at their largest valuation discount to the broad market since the dot com bubble of the early 2000s, BlackRock CIO of U.S. fundamental equities Tony DeSpirito said in a new research note. (6/22/2021)

Evie Liu, in Barron’s, reached about the same conclusion:

Investors have been favoring stocks, and assets such as cryptocurrencies, that look a lot like lottery tickets, taking on a high probability of poor returns for a small chance of large gains. That has bid up the prices of riskier stocks, while leaving more-stable stocks underappreciated.

“If you think about what happened to GameStop, the popularity of Dogecoin, the increasing online trading, and the high volume of call buying in the options market, investors have really been embracing risk,” says Nick Kalivas, Invesco’s head of factor strategy.

As concerns about a market correction bubble up, however, it might make sense to shift part of your stock portfolio into more-defensive names [including] high-quality stocks with strong fundamentals—higher margins, healthier balance sheets, and more-consistent cash flows. (“With correction fears rising, it’s time to explore underappreciated, low volatility and quality stocks,” Barrons.com, 5/27/2021)

Thanks …

To all of our readers (now more than 2,000,000 in total, which still strikes me as endlessly amazing) and to the good folks who’ve continued to support MFO as we’ve worked through options for our future: the folks S&F Investment Advisors, Wilson, Martin (thank you, sir, for everything – I’ll try to keep my brain in gear, my better half happy and my spirits high!), the incomparable Victoria Odinotska and our PayPal subscribers: Greg, William, Matthew (take care, sir, and thanks!), William, Brian, David, and Doug.

Chip and I will spend much of the month of July in New York, starting with her son’s wedding in mid-July and our retreat to the Finger Lakes region (I’m already working on Wine Trail priorities) in the second half of the month. Our original plan was to place the Observer on hiatus for a month but we already have a half dozen stories in the pipeline, from a profile of the best international small-cap fund around to the impending launch of a whole new series of funds from T. Rowe Price. With your kind support, I suspect that we’ll share a lite issue with you on August 1st.

As ever,