Running them, not assessing them.

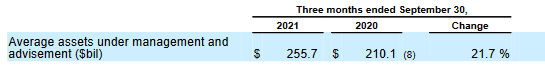

Morningstar runs a booming, global asset management business. They have $255 billion under management and advisement (as of 9/30/21).

Of that, $50.5 billion are assets under management, primarily through their Managed Portfolios and Institutional Asset Management services.

They also have 116,627 Morningstar.com Premium members and 17,182 Morningstar Direct licensees.

The managed portfolios traditionally used outside, actively managed funds. In 2018, Morningstar decided they could do better and launched their own family of sub-advised mutual funds to use in the service. In doing so, they severed relationships with some of the managers they’d traditionally relied on, either because the managers didn’t fit or weren’t thrilled with the prospect of substantially lower compensation for their services. In covering the launch (“The Morningstar Minute,” 5/2018), we concluded:

I hope the Morningstar funds do brilliantly well. They represent an interesting experiment, and the financial security of a lot of people rests on them. They seem thoughtfully designed, and their emphasis on cost minimization likely serves their investors’ interests. Nonetheless, the “sleeves for star managers” strategy is hard, as illustrated by the manager turnover at, and occasional liquidations of, the Litman Gregory Masters funds. The “masters” at their Smaller Companies fund (since liquidated), for instance, tend to fall from favor pretty quickly; the fund has had 20 masters since launch in 2003, with some teams out within three years.

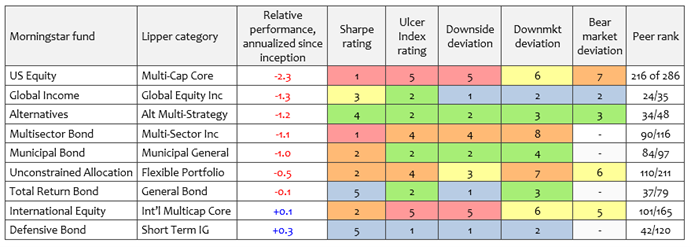

After three years, the records for the Morningstar funds are unimpressive. Below is a simplified chart assessing each fund. The first data column is its annual performance relative to its peers; Morningstar US Equity, as an example, trails its average peer by 2.3% per year. The remaining columns reflect each fund’s quintile performance (top 20%, second 20%…) for risk-adjusted returns (Sharpe and the Ulcer Index) and volatility (downside, down market, and bear market deviations). The simplest strategy: look for blue cells, avoid red ones.

Preliminary conclusion: with the exception of Morningstar Defensive Bond (an MFO Great Owl fund) and Morningstar Total Return Bond, their funds are mediocre or worse.

And Morningstar US Equity (MSTQX)? 16 managers (Westwood, Wasatch, MFS, Diamond Hill, ClearBridge, and Easterly Partners), 3 years, returns trailing 80-90% of its peers, one star, high risk, zero manager investment.

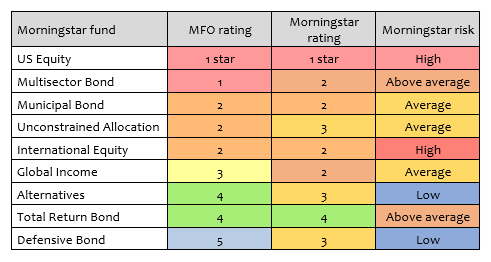

Lest you think that Lipper or MFO is somehow biased, here is Morningstar’s own assessment of their funds.

If we grabbed a hundred random samples of nine funds each, we would expect to see three-, four-, or five-star funds in the average sample. Morningstar has one. You’d also predict three one- and two-star funds. Morningstar offers five.

Let’s be blunt: if fund ratings are reliable, you would have been much better off picking funds at random than entrusting your money to Morningstar.

There are two useful conclusions

- All strategies embed assumptions about markets. When the assumptions are wrong, the strategy falters. Most investors assume that stock prices follow earnings: companies that make more see their stock prices rise. True in the long term, often false in the short term. In mid2020, there was a strong inverse correlation between earnings and stock price: companies that earned the most saw prices fall. In the fourth quarter of 2020, small caps with no earnings – pretty much the junkiest slice of the domestic equity market – rose by more than 40%. Failure doesn’t require the managers to be wrong; it just requires them to be out-of-step.

Some managers are, of course, wrong. A lot. When we set the MFO Premium screener for the worst-case (trailing your peers for 1-, 3-, 5- and 10-year periods with extremely high expenses and intolerable risk), you end up with a list of 20 funds – some with hundreds of millions in assets – that you’d never want to own.

In crazy markets, the sanest investors are the hardest hit.

Traditionally markets embraced and then wrung out the crazies on a seven-year cycle. The Fed’s impulse to protect us by propping up markets has likely delayed, but not prevented, the next cataclysmic reckoning.

- The best informed and best-resourced professionals cannot assemble star portfolios consistently. Morningstar can’t. Litman Gregory couldn’t. FundX can’t, consistently.

I can’t. In all likelihood, you can’t. So stop obsessing about it.

You can make good decisions which strengthen your financial prospects. We’ve consistently argued that it’s a simple four-step process:

- Determine your goals and resources. Why are you investing? When will you need the money? Reasonable goals might be having enough ready cash to get by for several months if you had no income, a college savings portfolio that might allow your child to graduate with under $20,000 in debt (depending on who’s calculating it, the average undergraduate college debt is $30,000-40,000 with an average monthly payment of $400 for a decade), or a retirement portfolio that could replace half of your current income.

- Set up a strategic plan: an allocation that gives you the best chance of getting there. In general, investing more than 50% of your portfolio in risk assets (aka stocks) or more than 0.1% of your portfolio in damned silly trinkets (cryptocurrencies, NTFs, fractional ownership of fine art, blank check SPACs) is a bad idea unless your willingness to stick with a losing investment spans a period of decades. We’re not making this up. There are 300+ stock funds that took more than ten years to recover from their worst stumble.

- Set up a tactical plan: a limited number of funds and ETFs to bring the strategic plan to life. Our criteria have always been the same: managers who’ve proved themselves across a variety of market conditions, whose strategy makes enough sense that you can explain it to your spouse, a profound risk consciousness, and a deep personal investment in the funds they offer.

- Fund your plan automatically. The traditional set-aside for retirement was 10% of your income; my college’s consultants claim that any reasonable chance of success requires something closer to 20%. No one will ever do that if it takes an act of will on the 1st of each month. An automatic investing plan saves you.

- Go enjoy life. After all, isn’t that the purpose of the money? To make a good life possible, not to become your life. Read a book (15-30 minutes a day thwarts both dementia and depression!). Get in the habit of starting each day with a bit of coffee and a bit of journaling. Say something nice to the first person you see, every day. Spend as much time as humanly possible away from screens and with nature … or friends, pets, children, community.

And when you do, thank Morningstar for helping you think more clearly about it all!