There are days when the world seems unnecessarily out of whack. Runways in London are melting, doctors and pharmacies are denying basic legal reproductive care to women because of fear of prosecution, and corporations are hiding more and more dark money contributions. It doesn’t matter where you stand politically; both parties are rollicking in the dark. Many people are working to make the world a better place, and many more seem stunned and appalled. One of the strategies that was very much in vogue last year was putting your money where your beliefs are; that is, investing in funds and ETFs that espoused some form of sustainable / responsible / green discipline. Bloomberg’s Saijel Kishan reports (2/3/2022) that

While definitions of environmental, social and governance investing vary — it can mean putting your money in anything from a wind-energy company to a Silicon Valley tech giant — assets are set to balloon to $50 trillion by 2025 from about $35 trillion, according to estimates from Bloomberg Intelligence. The growth has been spurred by record-breaking fund inflows amid concerns about climate change and other societal issues.

Sensing money to be made, firms quickly promoted (or cobbled together) about 80 new ESG funds in 2021. But then 2022 happened: many tech-heavy green funds cratered along with the market, fossil fuel producers soared, and ESG funds saw their first outflows in years.

This seems like an appropriate time to look at ESG investing in general and ESG funds in particular.

There are two parts to this piece. Our August essay presents an overview of ESG investing, where it comes from, and the different approaches employed. It touches on whether ESG can make sense from an investment (money-making) perspective. In October, we will take a look at how some rating services and fund families employ these approaches. Why, for example, did S&P drop Tesla from its ESG list?

Hopefully, both parts will give readers something to think about. Why does one want to invest in sustainable companies? It could be for ethical or religious reasons, because one wants to make a difference, or one may simply look at ESG investing as a path to better profits.

What are E, S, and G?

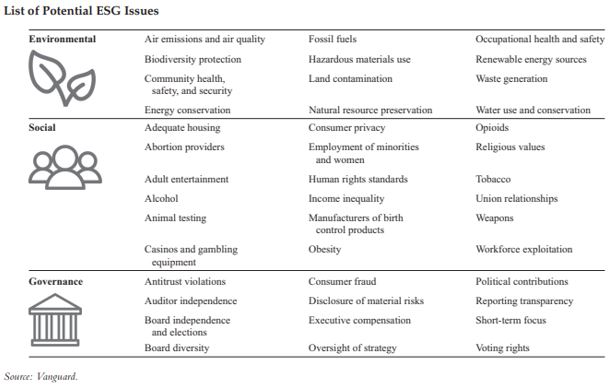

Environmental, Social, and Governance focused investing can mean different things to different people. Here is a graphic from Vanguard showing some areas that Vanguard feels come under these headings.

The SEC has its own set of examples. For social issues, it includes “diversity and inclusion, human rights, specific faith-based issues, the health and safety of employees, customers, and consumers locally and/or globally, or whether the company invests in its community, as well as how such issues are addressed by other companies in a supply chain.”

The SEC has its own set of examples. For social issues, it includes “diversity and inclusion, human rights, specific faith-based issues, the health and safety of employees, customers, and consumers locally and/or globally, or whether the company invests in its community, as well as how such issues are addressed by other companies in a supply chain.”

People tend to have a pretty good sense of what environmental issues are, or at least the ones that are important to them. Basically, clean air, clean water, clean land, and whatever it takes to make that happen.

At first glance, governance seems to be a bit different from environmental and social issues. Governance is concerned directly with how well a company is run and how it treats those in its ecosystem (employees, clients, vendors) as opposed to a company’s effects on the environment and on people generally.

In the end, the particular classification isn’t that important. Vanguard considers workplace safety an environmental issue (see graphic above). I would have classified it as a social concern along with other workplace issues like equal opportunity, parental leave, and adequate healthcare. One could even make an argument for it being a governance issue, as it relates to employment and how a company manages its workers.

Perhaps because it isn’t as intuitive as environmental and social issues, governance merits a bit more exposition. Well-run companies can do a lot of damage – think about an efficient, legally run coal plant. Scrubbers and all, this is not a clean process. But when companies are poorly run, when they hide what they are doing, when they disregard input from stakeholders – shareholders but also workers and customers and neighbors – they risk harm not only to others but ultimately to their own business.

Enron is a textbook example of a company with poor governance. Little transparency, ethically dubious practices, shareholder/employee abuse (the company froze Enron stock in the 401(k) plan, but not for the executives), and more. Of course, not every company is a potential Enron, though many are ethically challenged or may simply feel that minor transgressions, like white lies, are relatively harmless.

Enron is a textbook example of a company with poor governance. Little transparency, ethically dubious practices, shareholder/employee abuse (the company froze Enron stock in the 401(k) plan, but not for the executives), and more. Of course, not every company is a potential Enron, though many are ethically challenged or may simply feel that minor transgressions, like white lies, are relatively harmless.

Personal experience in very small startups has left me sensitive to these concerns. The board of one startup did not hold an annual shareholder meeting for three years. It was so scared of facing its investors that when it did hold the shareholder meeting, it hired an armed guard to stand next to the board. The shareholders immediately insisted that the guard be removed; violence did not ensue.

The Evolution and Practices of ESG Investing

Governance was somewhat of a latecomer to the game. ESG investing started out as socially responsible investing (SRI), emphasizing social concerns nearly a century ago. Much longer, actually, but the focus here is on mutual funds, so we can’t really go back much beyond the 1920s.

The Pioneer Fund (the second oldest U.S. mutual fund) was founded as the Fidelity Mutual Trust in 1928 by an ecclesiastic group. Its objective was to screen out alcohol, tobacco, and gambling companies, aka “sin stocks.” It fairly well typifies the early funds – religious underpinnings, a focus on social issues, and the use of fairly stringent “negative screens.”

In negative screening, a fund or investor absolutely excludes from consideration any company that does something “bad”. That could be manufacturing cigarettes or, as became more of a concern in the sixties, manufacturing weapons. While the screens tend to be absolute, what is being screened out doesn’t have to be. For example, a screen might exclude absolutely all companies taking in more than 5% of their revenue from tobacco. So even absolutes can be sort of relative.

In the sixties and seventies, a number of trends served to broaden the scope of SRI funds. Notably, of course, was the environmental movement, with such landmarks as the publication of Silent Spring in 1962 and the first Earth Day in 1970. The sixties were also notable for major social movements, including civil rights and gender equality, among others. SRI funds broadened their scope and incorporated positive screenings.

In their book Ethical Investing (1984), Amy Domini and Peter Kinder describe positive screening as an “approach [that] compliments the avoidance [negative screening] approach. Those adopting it seek investments in companies that enhance the quality of life.” A few examples of positive screens are a concern for safety (both employee and product), community involvement, energy conservation, and clean energy production.

Many positive screens, such as workplace practices, are broad and could be applied to almost any company. Others, like clean energy, are narrowly focused on particular industries. Funds that concentrate on these sectors may nevertheless also incorporate other considerations. For example, New Alternatives Fund (investing in alternative energy) joined with the vast majority of SRI funds in the eighties in avoiding companies doing business in South Africa in opposition to apartheid.

Rather than merely avoid “bad” companies and profit from “good” ones, another approach is to actively work to change company practices for the better. This seems like a recent phenomenon. In a way, it is. It is becoming more widespread and better known. Though as a tactic, shareholder activism dates all the way back to the first company to issue stock, the Dutch East India Company.

In addition to shareholder initiatives and proxy votes, institutional investors, including mutual fund families, often engage directly with companies to influence their practices. It can be difficult to know what a fund family is doing behind the scenes or how effective its efforts are. This is made more difficult by the fact that most fund companies manage many funds with varying objectives. Only a few in their stables may have an ESG focus. In this respect, it is easier to infer the actions of pure ESG fund families.

Third-party sources can be helpful here. Jon Hale, Morningstar’s director of ESG research for the Americas, observes that “Several … asset managers, especially Boston Trust Walden, Calvert, Nuveen, and Pax engage directly and often with companies about ESG issues and support most ESG-related shareholder resolutions” (6/24/2022).

Impact Investing

Impact investing is often described as making investments “with the intention to generate positive, measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return.” While an admirable objective, the term is often applied broadly to encompass all approaches regardless of how effective they are.

It is difficult to move the needle with screenings, whether positive or negative. Selling stock of a given company may depress the price of the stock, but only if enough people divest. Rarely does divesting have a significant impact on the cost of capital of a company, though that is the economic objective of divesting.

There are better ways to make an impact than by merely investing (or divesting) in the secondary market. One way is to go further, to push companies to change through activist investing described above. There are many funds and other vehicles available for this type of investing.

Another way to make an impact is to directly fund companies doing good work. That is not easy to do in the equity market. One alternative is to invest in entirely new or “good” industries such as renewable energy in an attempt to expand that industry. Bonds, because they are issued frequently and because they are accessible to individual investors as well as to institutions, are another vehicle available for impact investing.

Green bonds, aka climate bonds, are used to directly fund projects that address environmental concerns. A plain English presentation (2018), including pros and cons, was produced by the folks at Brown Advisory, a distinguished ESG investor. In the past few years, several bond mutual funds have been launched with names including ESG, sustainable, or green. Typically these funds go beyond bonds that have been certified “green.” So before investing, take a look at what is in their portfolios.

Performance

In the end, for many investors, it is ultimately all about performance. The classic knock against SRI/ESG investing is that by fishing in smaller pools, returns cannot mathematically be superior. A counterargument is it’s a lot better to fish in smaller, cleaner pools than in huge, contaminated ones. By focusing on well-run companies, companies that engage their workforce and have more productive employees, and companies that plan for environmental changes, ESG investing concentrates on companies that perform better.

ESG can be viewed as a form of factor investing, a particularly appealing form. Unlike some factors, which seem to be little more than the results of data mining (like the Superbowl indicator for the stock market), it has an underlying theory as well as correlation. In addition, so long as ESG investing doesn’t reduce returns, it offers a way to invest in “good” companies.

Studies on ESG performance tend to be mixed. Looking at the results of 2,000 studies done from 1970-2014, a meta-analysis concluded: “The business case for ESG investing is empirically well founded. … The large majority of studies report positive findings.” In other words, ESG investing does not come out worse and may do marginally better than non-ESG investing.

The bottom line

Investors consider ESG investing for a variety of reasons. For some, climate change is an existential threat that trumps everything else. For others, it may be important not only how clean a company is but how good a citizen it is and how it treats its stakeholders. Think about what matters to you, and then go beyond the ESG label to find funds that best address your concerns.