China has long been the driver of returns in the emerging markets, both because it is the largest emerging market and because the fortunes of other emerging economies are inextricably linked to China through trade, investment, and direct competition.

After a substantial correction which, at its worst, wiped $1.5 trillion in market cap off the books, China’s cheerleaders are speaking up. In August, BlackRock argued that China wasn’t really emerging and that investors should triple their exposure to Chinese equities. They then launched a mutual fund for Chinese investors, which drew $1 billion in its first week. Sadly, though, domestic investors have committed only $10 billion to BlackRock’s China funds:

In case you weren’t paying attention, in late November, BlackRock upgraded Chinese stocks, saying “the time to position in China is now.”

Fidelity echoes BlackRock’s enthusiasm. “China’s recent commotion is just business as usual,” they aver. Xiaoting Zhao, portfolio manager of Fidelity Emerging Asia Fund, allows that “some of the[reform] measures and execution of the regulation may be a bit rough in the beginning, but I believe they will improve in the medium term.” Perhaps not coincidentally, Fidelity was the second foreign firm – behind only BlackRock – to be permitted to open a mutual fund for Chinese investors.

Vanguard has filed to launch a new fund, Vanguard Select China Stock Fund. The plan is to split the assets between Baillie Gifford and Wellington Management. The fund will charge a relatively hefty 0.83%. Polen China Growth, also in the pipeline, will have competent and shareholder-oriented management teams.

What’s not to love?

The enthusiasm for China investing is driven by one economic reality (there’s a huge amount of money to be made there, if only by the fund companies) and two articles of faith:

- China is a “normal” country, nice people whose highest goal is economic security, transparent financial markets, and consumer celebration.

- Chinese officials will quietly manage away any challenges in their evolution toward normality.

To be clear, the case of investing in China becomes tenuous if either of those happy assumptions is disproven. The most prominent voice challenging them is George Soros.

At the heart of this conflict is the reality that the two nations represent systems of governance that are diametrically opposed. The U.S. stands for a democratic, open society in which the role of the government is to protect the freedom of the individual. Mr. Xi believes Mao Zedong invented a superior form of organization, which he is carrying on: a totalitarian closed society in which the individual is subordinated to the one-party state. It is superior, in this view, because it is more disciplined, stronger and therefore bound to prevail in a contest.

Relations between China and the U.S. are rapidly deteriorating and may lead to war. Mr. Xi has made clear that he intends to take possession of Taiwan within the next decade, and he is increasing China’s military capacity accordingly.

He also faces an important domestic hurdle in 2022, when he intends to break the established system of succession to remain president for life. He feels that he needs at least another decade to concentrate the power of the one-party state and its military in his own hands. He knows that his plan has many enemies, and he wants to make sure they won’t have the ability to resist him. (“Xi’s Dictatorship Threatens the Chinese State,” Wall Street Journal, 8/14/2021)

Google “Xi Jinping power” and you’ll find some reputable people (and a bunch of idiots) who work with the same set of concerns: President Xi has amassed more power than any Chinese leader since Mao (who was, one notes, responsible for the deaths of 65 million Chinese in his own drive for national power and purity), is intent on gathering more and is not driven by the desire to be a normal, market-oriented, middle-class country.

Google “Xi Jinping power” and you’ll find some reputable people (and a bunch of idiots) who work with the same set of concerns: President Xi has amassed more power than any Chinese leader since Mao (who was, one notes, responsible for the deaths of 65 million Chinese in his own drive for national power and purity), is intent on gathering more and is not driven by the desire to be a normal, market-oriented, middle-class country.

In general, the combination of unchecked power and a messianic vision has ended poorly. It does not require “evil genius” to send nations off a cliff, simple boneheadedness is generally enough. Barbara Tuchman’s The March of Folly: From Troy to Vietnam (1984) is not her best book but it’s a fairly sobering discussion of two questions, “Why do holders of high office so often act contrary to the way reason points and enlightened self-interest suggests? Why does intelligent mental process seem so often not to function?”

While the word “Soros” appears nowhere on the BlackRock website (feel free to search it), they did offer two responses to Mr. Soros. First, on CNBC a BlackRock spokesman assured viewers that “Through our investment activity, US-based asset managers and other financial institutions contribute to the economic interconnectedness of the world’s two largest economies” (“BlackRock responds to George Soros’ criticism over China investments,” CNBC, 8/8/2021). And, second, they launched a billion-dollar fund, adding that “it believes it can help China to address its growing retirement crisis by providing retirement system expertise, products, and services” (CNBC).

That’s in line with an observation made by the Wall Street Journal in 2020: “China Has One Powerful Friend Left in the U.S.: Wall Street” (it’s a fascinating article, for those with paid access, authored by Lingling Wei, Bob Davis, and Dawn Lim, 2/2/2020). Not everyone in the financial community shares the general gluttonous commitment to China and more China. In summer we noted Andrew Foster’s incredibly thoughtful reflections on China’s divergence from the path to normalcy. We noted last month, Robert Gardiner of Grandeur Peak shared a cautious, “keeping our eyes on the exit” perspective. This month, Laura Geritz of Rondure Global Advisors notes that

We believe the world is witnessing the emergence of a new political chapter in China’s history …. Xi has positioned himself to rule unbound by the reform minded restraints of the past 40 years. What will he do with the power? We are beginning to see. (“Chinese Dreams, American Dreams and Pure Fantasia,” 3Q21)

Where do that leave emerging markets investors?

Excellent question!

The most successful EM funds of the past decade share two distinguishing characteristics: (1) a focus on large-cap growth stocks and (2) substantial exposure to China. The table below shows the 12 highest-return diversified EM funds and ETFs of the past five years, through mid-November 2021.

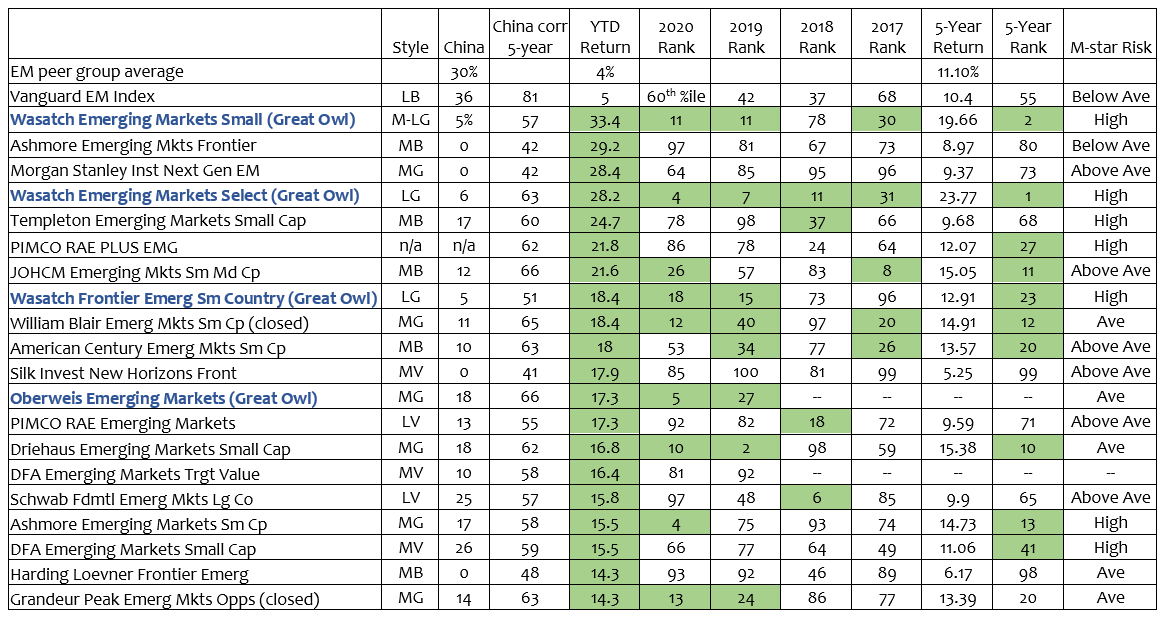

It illustrates four clusters of values: (1) investment style – mostly Large Growth with one fund at the edge of Midcap Growth and Large Growth; (2) exposure to China, as measured by both direct investments in China and by the fund’s correlation to a pure China ETF; (3) the fund’s performance in absolute and relative terms and (4) Morningstar’s assessment of their relative riskiness. The Lipper EM equity peer group and Vanguard’s venerable EM index fund are included as benchmarks.

Any cell with above-average performance is shaded in green.

Funds designated “Great Owl funds” by MFO are those that have posted consistently top quintile risk-adjusted returns for all measurement periods longer than one year. They highlight funds that have shown strong risk-adjusted returns and have done so consistently.

Contrarily, the most successful EM funds of 2021 share two distinguishing characteristics: (1) a decisive share away from Large and Growth and (2) vastly reduced exposure to China. The table below shows the 25 best EM funds of the past five years, through mid-November 2021.

Bottom line

Investing is an inherently risky activity. The key to success is to understand and calibrate the risks you’re taking. We suspect that overweighting investments in an increasingly megalomaniacal regime might incur rather more risk than BlackRock and other apologists admit to. Similarly, an exclusive commitment to large + growth might be akin to skating to where the puck was, rather than to where it’s going to be.

Fortunately, a China-light portfolio is not inconsistent with double-digit long-term returns. If you share Mr. Soros’ concerns, your due-diligence list might incorporate the funds – especially the Great Owls – highlighted above.