“As for me, I baptize you with water for repentance, but He who is coming after me is mightier than I, and I am not fit to remove His sandals; He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire.” Matthew 3:11

“Making far more than a single statement, Cantigny was the doughboys’ baptism by fire, and for those who survived, it became the crucible by which they would measure all subsequent experience, in large-scale fighting at Soissons and the grand Meuse-Argonne offensive … May 28, 1918, was the US military’s coming-of-age—the day it crossed a historical no-man’s-land that separated contemporary fighting methods from the muskets and cannon of the nineteenth century.

Through the 1920s and ‘30s, ‘Cantigny’ remained a symbol of American sacrifice and triumph, a uniting emblem that finally exorcised the dividing demons of the Civil War in a way the Spanish-American War never could. But then came Pearl Harbor. And D-Day. And the Bulge. And in the wake of these epochal events, the 1st Division’s attack at Cantigny lapsed into footnotes, its story left to slumber for a century … the soldiers’ private writings, official reports and memoirs are now all they we have … they chronicle the front-line education under machine-gun and artillery fire that turned college students and young professionals into leaders of men.”

Matthew Davenport, First Over There: The Attack on Cantigny, America’s First Battle of World War I (2015)

To my younger colleagues: welcome to your Cantigny. There is very little question that the events of 2020, and perhaps 2021, will shape the way you view the world, your opportunities, and your obligations, for decades to come.

Great events do that to people. The question is how you choose to let those events play in your mind. And you do have that choice.

Your choice matters, a lot.

One way we choose how we’re affected is by choosing how we “frame” what we’re seeing. We know that all communication is ambiguous, it requires interpretation on our part. Someone smiles at you. What does it mean? Are they smirking? Do they know something you don’t? Are they bonding with you? Flirting with you? Trying to avoid talking to you? All of those are possible but you need to pick the version you’re going to react to. The version you pick is your frame for the interaction.

Our frame guides our choice. Is this “hanging with my friend group” or “dealing with a threat”? Is it “negotiating a date” or “trying to figure out a meal after class”?

Framing theory says that other people, frequently the media, help teach you which frame to use when you’re making sense of public events. Once we know what’s going on, we start noticing facts that confirm it, we fail to notice things that might challenge it, and we interpret what’s going on within the rules set by our frame.

How does this help us think about Covid-19? The public health frame leads us to view this as another of a long series of public health emergencies (our 5th pandemic in 100 years) that needs to be understood and responded to, through evidence provided by the medical and scientific communities. A crisis frame leads us to view this as an unprecedented threat that might spiral out of control at any time. People who accept a crisis frame are buying guns and staggering out of crowded stores clutching armloads of toilet paper and frozen veggies that they don’t even like. They don’t have a long-term plan other than to hide and imagine the worst. This frame is encouraged by many on social and non-traditional media; it’s good for generating clicks and retweets. A tribal frame leads us to view this as a manufactured crisis; “they” are whipping us to hysteria to discredit “us” and our leaders. People relying on what’s called “tribal epistemology” accept as “facts” only things that support their tribe’s interests and beliefs. They view disagreement with their perspective as an attack whose purpose is to weaken us. People who accept a tribal frame are, mostly, defiant of the official explanations and insistent that they’re going to go about their lives as usual; the large St. Patrick’s Day bar crowds, now-packed beaches, and unmasked protesters would reflect the rejection of the legitimacy of scientific and public health advice.

Likewise, how might you think about your investments and the decades ahead?

Let’s share three bits of information that might help you frame the events raging around us.

1. This too shall pass.

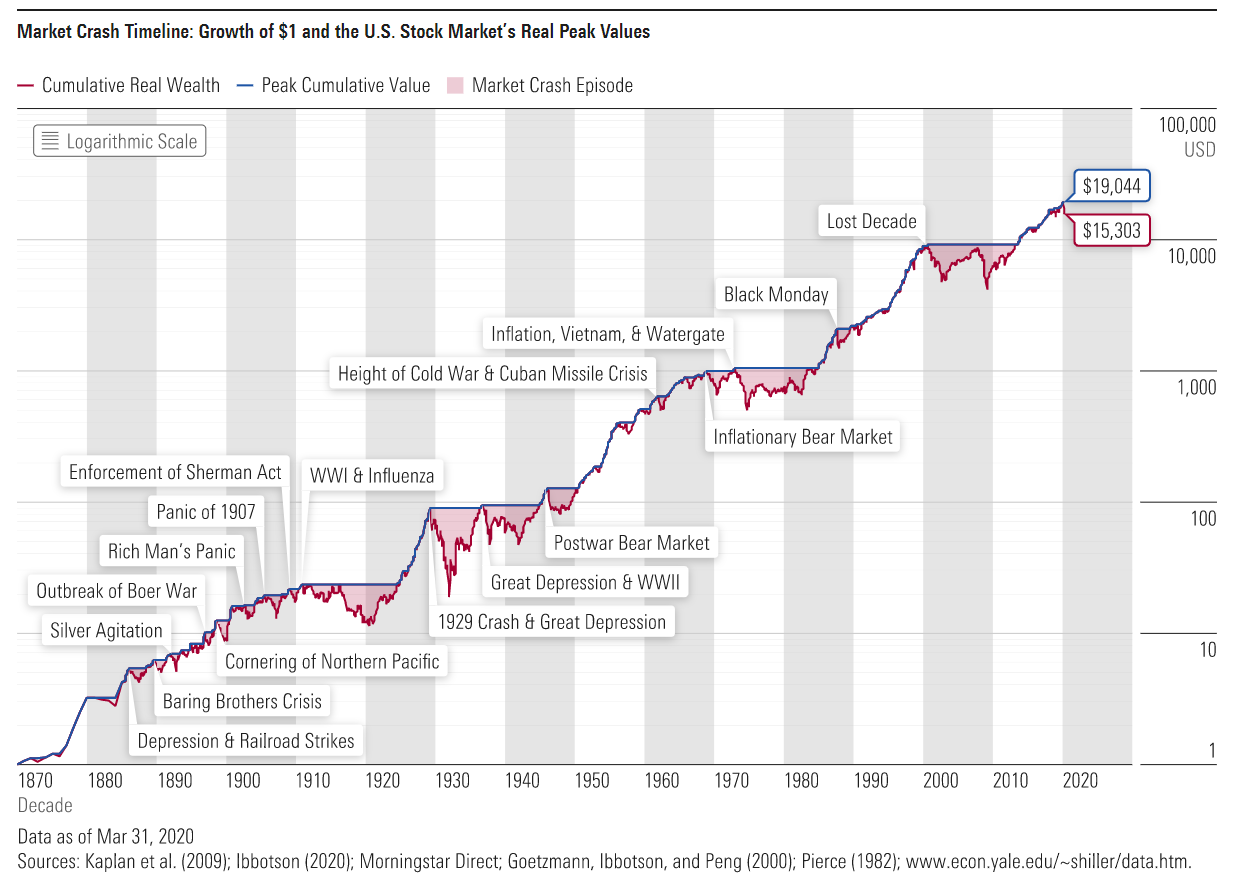

Markets go up, markets go down. For those with a short time horizon and a large exposure to the stock market, that can be devastating. For you, folks with a long time horizon and small exposure to the stock market (relative to your lifetime investments), it’s mostly noise. The good folks at Morningstar created (What Prior Market Crashes Can Teach Us About Navigating the Current One, 4/16/2020), and gave us permission to share, a picture of the long-term significance of short-term terrors.

Pick the worst possible day to invest, say the day before the onset of the Great Depression or day before the oil price shocks in 1973, and ask where you’d be 25 years later if you stuck with the plan, continued to invest and put more passion into your life than your portfolio.

The short answer is, “really well-off.”

2. A sharp, continued price decline now is the best gift you’ll ever receive.

For any asset, your eventual profit is driven by your purchase price. If you pay too much for a house, a car, a share of stock, or a relationship now, your eventual returns on the asset are going to be modest. Driven by corporate tax cuts, near-zero interest rates that made it easy for companies to buy back shares of their stocks (at the rate of $500 billion – $800 billion a year, making them the “dominant” source of stock market demand) and that made conservative investments fundamentally unattractive, stock prices rose to some of their highest levels in history.

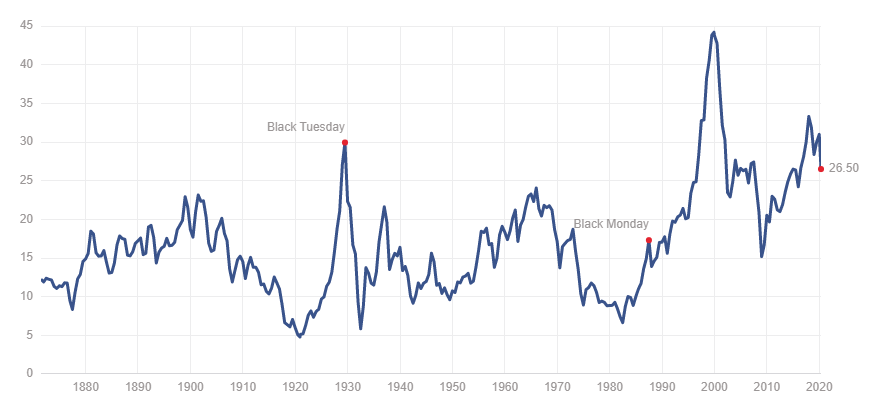

The chart below shows a cyclically-adjusted measure of stock market valuation, called the Shiller 10-year CAPE ratio. Dr. Shiller created the calculation to smooth out the effects of wild quarter-to-quarter gyrations and let us get a better sense of the underlying trend.

Right now, the Shiller PE is 26.5. The good news: that’s down from the 2019 peak when US stocks were the second most expensive in the last 140 years. The not-yet good news: that’s still mightily above the 140-year average price of about 16.

Because prices are high and our economy is mature, future returns from stocks are likely to be disappointing. Research Affiliates projected 1.5% returns, on average, for the next decade. BlackRock and Vanguard are a little more optimistic, GMO is a little less optimistic. All project a long period of disappointment … unless stock valuations return to earth.

For those of us who own lots of stocks and whose buying days are few, that’s bad. For those of us who own little stock and whose buying days stretch out for decades, that’s good.

3. Small investors have great opportunities to start.

In general, you need to do three things.

First, create as much balance in your life as possible. My grandparents never owned a car. My parents (dad, mostly) demanded a new car every three years. My siblings lease vehicles, which gives you “shiny” but no equity. I drive sensible used sedans. On whole, we probably need to ask, “did grandma get it right?” The most positive commentary amidst the current crisis is the folks who’ve suggested that the cult of Instagram influencers and cheap celebrity has faded and the fear-of-missing-out is daily less powerful. The short version: don’t embrace what you don’t need.

Second, create an emergency account in an insured, low-return account. The rule of thumb used to be “three to six months’ worth of expenses.” That’s not “three to six months of income,” that’s three to six months of DUG: Debt (mortgage or rent, loans, credit card minimums), Utilities, Groceries. Not Netflix, not upgrades, not my former Friday beerfest. Enough that you can forestall panic and plan reasonable next steps. Researchers think that $2500 is enough to actually get us through 80% of life’s traumas but folks with insecure incomes might shoot for more.

Third, begin small, automatic contributions to a zero-minimum fund that gives you some exposure to the world’s stock markets. In the long term, only equities return enough to make a substantial difference though they are gut-wrenchingly volatile in the short run. That’s why “automatic” matters: set yourself up to invest $50 (or $100 on the first of each month) via an automatic investing plan. Those can be set up, free, from most fund companies or online brokerages.

Fidelity has reduced the minimum initial investment on virtually all of its funds to zero. A young investor might reasonably start by looking at the Fidelity Asset Manager series. Each fund is well-diversified with exposure to US and foreign stocks and bonds, and its name tells you how much stock exposure you’re buying: Fidelity Asset Manager 20 (FASIX) is 20% stocks, for example. In general, less stock = less short-term volatility but also less long-term gains.

| 2020 losses | Five-year gains | |

| Asset Manager 20% (FASIX) | -2.2% | 3.1% |

| Asset Manager 40% (FFANX) | -5.0 | 3.9 |

| Asset Manager 60% (FSANX) | -8.3 | 4.2 |

| Asset Manager 85% (FAMRX) | -12.3 | 4.5 |

The Leuthold Group was founded in 1981 as an independent investment research firm and, in 1987, began offering mutual funds. Their model is called “tactical allocation,” which means that their exposure to stocks and other assets varies as their judgment of the asset’s attractiveness varies. They’re a rigorously quantitative group which allows the data, rather than their guts, to drive their decisions. Their flagship Leuthold Core Investment Fund (LCORX) has a four-star, Gold rating from Morningstar but a $10,000 minimum (albeit one waived at some online brokerages). The good news is that they have launched an ETF version, Leuthold Core ETF (LCR) which tracks LCORX, has no minimum investment requirement, and charges 0.86% in expenses which is far below the mutual fund’s charges. LCR is somewhat more adventurous than the Asset Manager series because it doesn’t lock you into a predictable level of equity exposure.

Bottom Line

What you don’t learn in the months ahead is as important as what you do. The strategies that thrive in 2020’s mad market are not a good guide to what will thrive in the succeeding years or decades. For now, long-tested strategies (e.g. low volatility investing) are lagging while gold (a long-term laggard) is soaring. In general, quality companies bought at reasonable prices and held for long periods work. Limiting your exposure to risky assets to the minimum needed to pursue your goals, works. Remembering that your portfolio is just a tool to help you enjoy a reasonable, reasonably secure stretch in late adulthood, works.

Greed fails. Impulse fails. Fear fails.

And you, dear reader, will not fail. Tune out the noise. Set aside the fear. Set up a plan that lets you pursue a slow and steady discipline. Ask how you can make a difference in the real world, in your neighborhood, and in the lives of those who depend on you. Have faith in your future. Have faith in ours. We’ll get through this together.