October 1, 2015

Dear friends,

Welcome to fall. Welcome to October, the time of pumpkins.

October’s a month of surprises, from the first morning that you see frost on the grass to the appearance of ghosts and ghouls at month’s end. (Also sports mascots. Don’t ask.) It’s a month famous of market crashes – 1929, 1987, 2008 – and for being the least hospitable to stocks. And it has the prospect of setting new records for political silliness and outbreaks of foot-in-mouth disease.

October’s a month of surprises, from the first morning that you see frost on the grass to the appearance of ghosts and ghouls at month’s end. (Also sports mascots. Don’t ask.) It’s a month famous of market crashes – 1929, 1987, 2008 – and for being the least hospitable to stocks. And it has the prospect of setting new records for political silliness and outbreaks of foot-in-mouth disease.

It’s the month of golden leaves, apple cider, backyard fires and weekend football. (I’m a bit torn. Sam Frasco, Augie’s quarterback, broke Ken Anderson’s school record for total offense – 469 yards in a game – and lost. In the next week, he broke his own record – 575 – and lost again.)

It’s the month where we discover that Oktoberfest actually takes place in September, and we’ve missed it.

In short, it’s a good month to be alive and to share with you.

Leuthold: a cyclical bear has commenced

As folks on our mailing list know, the Leuthold Group has concluded that a cyclical bear market has begun. They make the argument in the lead section of Perception for the Professional, their monthly report for paying research clients (and us). It’s pretty current, with data through September 8th. A late September update of that essay, posted on the Leuthold Group’s website, reiterates the conclusion: “We strongly suspect the decline from the September 17th intraday highs is the bear market’s second downleg, and we’d expect all major U.S. indexes to undercut their late August lows before this leg is complete.” While declines during the 3rd quarter took some of the edge off the market’s extreme valuation, they note with concern the buoyant optimism of the “buy the dips” crowd.

Who are they?

The Leuthold Group was founded in 1981 by Steve Leuthold, who is now mostly retired to Bar Harbor, Maine. (I’m intensely jealous.) They’re an independent firm that produces financial research for institutional investors. They do unparalleled quantitative work deeply informed by historical studies that other firms simply don’t attempt. They write well and thoughtfully.

Why pay any attention?

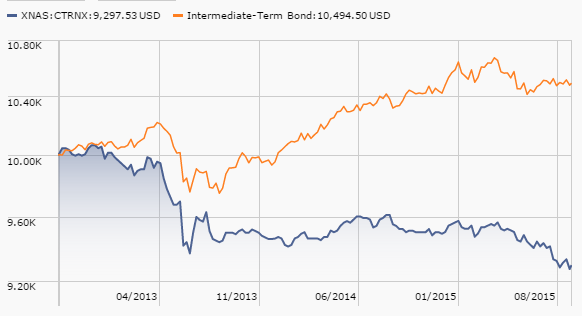

They write well and thoughtfully. Hadn’t I mentioned? Quite beyond that, they put their research into practice through the Leuthold Core (LCORX) and Leuthold Global (GLBLX) funds. Core was a distinguished “world allocation” fund before the term existed. $10,000 entrusted to Leuthold in 1995 would have grown to $53,000 today (10/01/2015). Over that same period, an investment in the Vanguard 500 Index Fund (VFINX) would have growth to $46,000 while the average tactical allocation manager would have managed to grow it to $26,000. All of which is to say, they’re not some ivory tower assemblage of perma-bears peddling esoteric strategies to the rubes.

What’s their argument?

The bottom line is that a cyclical bear began in August and it’s got a ways to go. Their bear market targets for the S&P 500 – based on a variety of different bear patterns – are in the range of 1500-1600; it began October at about 1940. The cluster of the Russell 2000 is around 1000; the October 1 open was 1100.

The S&P target was a composite drawn from the levels necessary to achieve:

- a reversion to 1957-present median valuations

- 50% retracement of gains from the October 2011 low

- the October 2007 peak

- the median decline in a postwar bear

- the March 2000 secular bull market peak

- 50% retracement of the gain from the March 2009 low

- April 2011 market peak

Each of those represents what some technicians see as a “support level” in a typical cyclical bear. Since Leuthold recognizes that it’s not possible to be both precise and meaningful, they look for clustered values. Most of the ones about lie between 1525 and 1615, so …

They address some of the self-justificatory blather (“it’s the most hated bull market in history,” to which they reply that sales of leveraged bull market funds and equity exposure by market-timing newsletters were at records for 2014 and much of 2015 which some might think of as showin’ some lovin’), then make two arguments:

- Market internals have been breaking down all summer.

- After the August declines, the market’s forward P/E ratio was still higher than it was at the peaks of the last three bull markets.

In their tactical portfolios, they’ve dropped their equity exposure to 35%. Their early September asset allocation in the portfolios (such as Leuthold Core LCORX and Leuthold Global GLBLX) was:

52% long equities

21% equity hedge a/k/a short for a net long of 31%

4% EM equities, which are in addition to the long position above

20% fixed income, with both EM and TIPS eliminated in August. The rest is relatively short and higher quality.

3% cash

They seem especially chary of energy stocks and modestly positive toward consumer discretionary and health care ones.

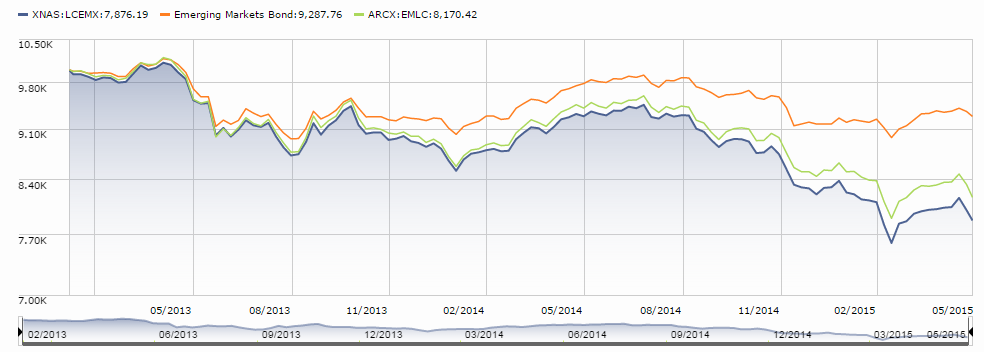

They are torn on the emerging markets. They argue that “there must be serious fundamental problems with any asset class that commands a Normalized P/E of only 13x at the peak (in May 2015) of one of the greatest liquidity-driven bull markets in history. We now expect EM valuations will undercut their 2008 lows before the current market decline has run its course. That washout might also serve up the best stock market bargains in many years…” (emphasis in original) Valuations are already so low that they’ve discussed overriding their own models but will not abandon their discipline in favor of their guts.

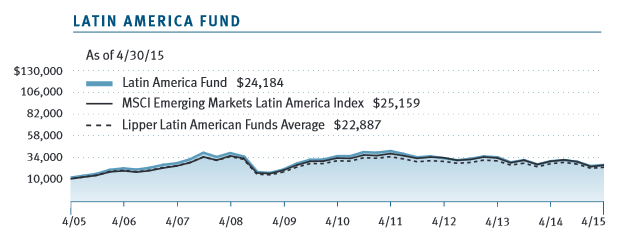

The turmoil in the emerging markets has struck down saints and sinners alike. The two emerging markets funds in my personal account, Seafarer Overseas Growth & Income (SFGIX) and Grandeur Peak Emerging Opportunities (GPEOX, closed) are down about 18% from their late May highs while the EM group as a whole has declined by just over 20%. As Ed Studzinski notes, below, those declines were occasioned by a panic over Chinese stocks which triggered a trillion dollar capital flight and a liquidity crisis.

Seafarer and Grandeur Peak both have splendid records, exceptional managers and success in managing through turmoil. Given the advice that we offered readers last month – briefly put, the worst time to fix a leaky roof is in a storm – I was struck by manager Andrew Foster’s thoughtful articulation of that same perspective in the context of the emerging markets. He made the argument in a September video, in which he and Kate Jaquet discussed risk and risk management in an emerging markets portfolio.

Seafarer and Grandeur Peak both have splendid records, exceptional managers and success in managing through turmoil. Given the advice that we offered readers last month – briefly put, the worst time to fix a leaky roof is in a storm – I was struck by manager Andrew Foster’s thoughtful articulation of that same perspective in the context of the emerging markets. He made the argument in a September video, in which he and Kate Jaquet discussed risk and risk management in an emerging markets portfolio.

Once a crisis begins to unfold, there’s very little we can do amid the crisis to really change how we manage the fund to somehow dampen down the risk or the exposure the fund has. .. The best way to control risk within the fund is preventative… to try and put in place a portfolio construction that anticipates different kinds of market conditions well ahead of time such that when the crisis unfolds or the volatility ensues that you’re at least reasonably well positioned for it.

The reason why it doesn’t make a great deal of sense to react substantially during a crisis is because most financial crises stem from liquidity panics or some sort of liquidity shortage. And so if you try and trade your portfolio or restructure it radically in the middle of such an event, you’re inevitably trading right into a liquidity panic. What you want to sell will be difficult to sell and you won’t realize efficient prices. What you want to buy – the stuff that might seem safe or might be able to steer you through the crisis – will inevitably be overpriced or expensive … [prices] tend to be at extremes. You’re going to manifest the risk in a more pronounced way and crystallize the loss you’re trying to avoid.

The solution he propounds is the same one you should adopt: Build an all-weather portfolio that manages to be “strong and happy” in good markets and “reasonably resilient” in bad ones.

A more striking response was offered by the good folks at Vulcan Value Partners whose Vulcan Value Partners Small Cap (VVPSX, closed) we profiled four years ago. Vulcan Value Partners does really good work (“all of our investment strategies are ranked in the top 1% of our peers since inception and both Large Cap and Focus are literally the best performing investment programs among their peers”), part and parcel of which is being really thoughtful about the risks they’re asking their partners to face. Their most recent shareholder letter is bracing:

A more striking response was offered by the good folks at Vulcan Value Partners whose Vulcan Value Partners Small Cap (VVPSX, closed) we profiled four years ago. Vulcan Value Partners does really good work (“all of our investment strategies are ranked in the top 1% of our peers since inception and both Large Cap and Focus are literally the best performing investment programs among their peers”), part and parcel of which is being really thoughtful about the risks they’re asking their partners to face. Their most recent shareholder letter is bracing:

In Small Cap, we have sold a number of positions at our estimate of fair value but have been unable to redeploy capital back into replacements at prices that provide us with a margin of safety. Consequently, cash levels are rising, and price to value ratios in the companies we do own are not as low as in Large Cap. Our investment philosophy tends to keep us fully invested most of the time. However, at extremes, cash levels can rise. We will not compromise on quality, and we will not pay fair value for anything. .. We encourage our Small Cap partners to reduce their small cap exposure in general and with us if they have better alternatives. At the very least, we strongly ask you to not add to your Small Cap allocation with us. There will be a day when we write the opposite of what we are writing today. We look forward to writing that letter, but for the time being Small Cap risks are rising and potential returns are falling. (Thanks for Press, one of the stalwarts of MFO’s discussion board, for bringing the letter to my attention.)

The Field Guide to Bears

Financial professionals tend to distinguish “cyclical” markets from “secular” ones. A secular bear market is a long-term decline that might last a decade or more. Such markets aren’t steady declines; rather, it’s an ongoing decline that’s punctuated by furious short-term market rallies – called “cyclical bulls” – that fizzle out. “Short term” is relative, of course. A short-term rally might roll on for 12-18 months before investors capitulate and the market crashes once again. As Barry Ritzholtz pointed out earlier this year, “Knowing one from the other isn’t always easy.”

There’s an old hiker’s joke that plays with the same challenge of knowing which sort of bear you’re facing:

Park visitors are advised to wear little bells on their clothes to make noise when hiking. The bell noise allows the bears to hear the hiker coming from a distance and not be startled by a hiker accidently sneaking up on them. This might cause a bear to charge. Hikers should also carry pepper spray in case they encounter a bear. Spraying the pepper in the air will irritate a bear’s sensitive nose and it will run away.

Park visitors are advised to wear little bells on their clothes to make noise when hiking. The bell noise allows the bears to hear the hiker coming from a distance and not be startled by a hiker accidently sneaking up on them. This might cause a bear to charge. Hikers should also carry pepper spray in case they encounter a bear. Spraying the pepper in the air will irritate a bear’s sensitive nose and it will run away.

It also a good idea to keep an eye out for fresh bear scat so you’ll know if there are bears in the area. People should be able to tell the difference between black bear scat and grizzly bear scat. Black bear scat is smaller and will be fibrous, with berry seeds and sometimes grass in it. Grizzly bear scat will have bells in it and smell like pepper spray.

Some Morningstar ETF Conference Observations

Overcast and drizzling in Chicago on the day Morningstar’s annual ETF Conference opened September 29, the 6th such event, with over 600 attendees. The US AUM is $2 trillion across 1780 predominately passive exchange traded products, or about 14% of total ETF and mutual fund assets. The ten largest ETFs , which include SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) and Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI), account more for nearly $570B, or about 30% of US AUM. Here is a link to Morningstar’s running summary of conference highlights.

Overcast and drizzling in Chicago on the day Morningstar’s annual ETF Conference opened September 29, the 6th such event, with over 600 attendees. The US AUM is $2 trillion across 1780 predominately passive exchange traded products, or about 14% of total ETF and mutual fund assets. The ten largest ETFs , which include SPDR S&P 500 ETF (SPY) and Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF (VTI), account more for nearly $570B, or about 30% of US AUM. Here is a link to Morningstar’s running summary of conference highlights.

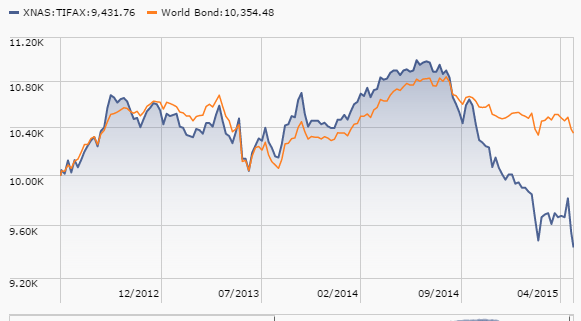

Joe Davis, Vanguard’s global head of investment strategy group, gave a similarly overcast and drizzling forecast of financial markets at his opening key note, entitled “Perspectives on a low growth world.” Vanguard believes GDP growth for next 50 years will be about half that of past 50 years, because of lack of levered investment, supply constraints, and weak global demand. That said, the US economy appears “resilient” compared to rest of world because of the “blood -letting” or deleveraging after the financial crisis. Corporate balances sheets have never been stronger. Banks are well capitalized.

US employment environment has no slack, with less than 2 candidates available for every job versus more than 7 in 2008. Soon Vanguard predicts there will be just 1 candidate for every job, which is tightest environment since 1990s. The issue with employment market is that the jobs favor occupations that have been facilitated by the advent of computer and information technology. Joe believes that situation contributes to economic disparity and “return on education has never been higher.”

Vanguard believes that the real threat to global economy is China, which is entering a period of slower growth, and attendant fall-out with emerging markets. He believes though China is both motivated and has proven its ability to have a “soft landing” that relies more on sustainable growth, if slower, as it transitions to more of a consumer-based economy.

Given the fragility of the global economy, Vanguard does not see interest rates being raised above 1% for the foreseeable future. End of the day, it estimates investors can earn 3-6% return next five year via a 60/40 balanced fund.

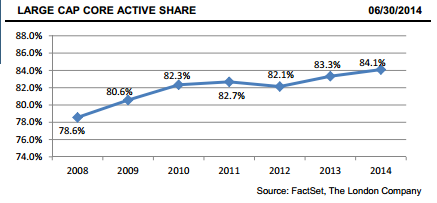

J. Martijn Cremers and Antti Petajisto introduced a measure of active portfolio management in 2009, called Active Share, which represents the share of portfolio holdings that differ from the benchmark index holdings. A formal definition and explanation can be found here (scroll to bottom of page), extracted from their paper “How Active Is Your Fund Manager? A New Measure That Predicts Performance.”

Not everybody agrees that the measure “Predicts Performance.” AQR’s Andrea Frazzini, a principal on the firm’s Capital Management Global Stock Selection team, argued against the measure in his presentation “Deactivating Active Share.” While a useful risk measure, he states it “does not predict actual fund returns; within individual benchmarks, it is as likely to correlate positively with performance as it is to correlate negatively.” In other words, statistically indistinguishable.

AQR examined the same data as the original study and found the same quantitative result, but reached a different implication. Andrea believes the 2% higher returns versus the benchmark the original paper touted is not because of so-called high active share, but because the small cap active managers during the evaluation period happened to outperform their benchmarks. Once you break down the data by benchmark, he finds no convincing argument.

He does believe it represents a helpful risk measure. Specifically, he views it as a measure of activity. In his view, high active share means concentrated portfolios that can have high over-performance or high under-performance, but it does not reliably predict which.

He also sees its value in helping flag closest index funds that charge high fees, since index funds by definition have zero active share.

Why is a large firm like AQR with $136B in AUM calling a couple professors to task on this measure? Andrea believes the industry moved too fast and went too far in relying on its significance.

The folks at AlphaArchitect offer up a more modest perspective and help frame the debate in their paper, ”The Active Share Debate: AQR versus the Academics.”

Charles Ellis, renowned author and founder of Greenwich Associates, gave the lunchtime keynote presentation. It was entitled “Falling Short: The Looming Problem with 401(k)s and How To Solve It.”

Charles Ellis, renowned author and founder of Greenwich Associates, gave the lunchtime keynote presentation. It was entitled “Falling Short: The Looming Problem with 401(k)s and How To Solve It.”

He started by saying he had “no intention to make an agreeable conversation,” since his topic addressed the “most important challenge to our investment world.”

The 401(k) plans, which he traces to John D. Rockefeller’s gift to his Standard Oil employees, are falling short of where they need to be to support an aging population whose life expectancy keeps increasing.

He states that $110K is the median 401(k) plus IRA value for 65 year olds, which is simply not enough to life off for 15 years, let alone 25.

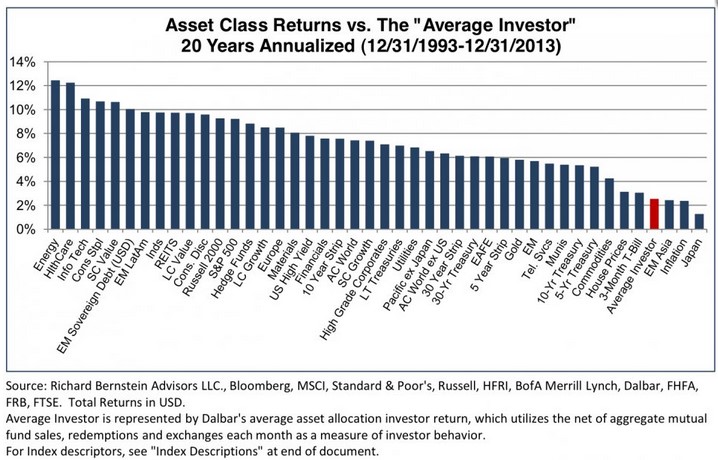

The reasons for the shortfall include employers offering a “You’re in control” plan, when most people have never had experience with investing and inevitably made decisions badly. It’s too easy to opt out, for example, or make an early withdrawal.

The solution, if addressed early enough, is to recognize that 70 is the new 65. If folks delay drawing on social security from say age 62 to 70, that additional 8 years represents an increase of 76% benefit. He argues that folks should continue to work during those years to make up the shortfall, especially since normal expenses at that time tend to be decreasing.

He concluded with a passionate plea to “Help America get it right…take action soon!” His argument and recommendations are detailed in his new book with co-authors Alicia Munnell and Andrew Eschtruth, entitled “Falling Short: The Coming Retirement Crisis and What to Do About It.”

We Are Where We Are!

By Edward A. Studzinski

By Edward A. Studzinski

“Cynicism is an unpleasant way of saying the truth.”

Lillian Hellman

Current Events:

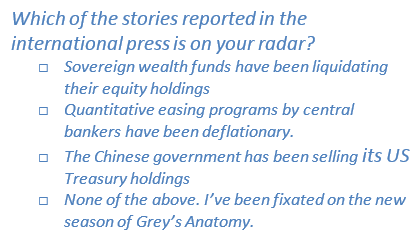

While we may be where we are, it is worth a few moments to talk about how we got here. In recent months the dichotomy between the news agendas of the U.S. financial press and the international press has become increasingly obvious. At the beginning of August, a headline on the front page of the Financial Times read, “One Trillion Dollars in Capital Flees Emerging Markets.” I looked in vain for a similar story in The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times. There were many stories about the next Federal Reserve meeting and whether they would raise rates, stories about Hillary Clinton’s email server, and stories about Apple’s new products to come, but nothing about that capital flight from the emerging markets.

We then had the Chinese currency devaluation with varying interpretations on the motivation. Let me run a theme by you that was making the rounds of institutional investors outside of the U.S. and was reported at that time. In July there was a meeting of the International Monetary Fund in Europe. One of the issues to be considered was whether or not China’s currency, the renminbi, would be included in the basket of currencies against which countries could have special drawing (borrowing) rights. This would effectively have given the Chinese currency the status of a reserve currency by the IMF. The IMF’s staff, whose response sounded like it could have been drafted by the U.S. Treasury, argued against including the renminbi. While the issue is not yet settled, the Executive Directors accepted the staff report and will recommend extending the lifespan of the current basket, now set to expire December 31, until at least September 2016. At the least, that would lock out the renminbi for another year. The story I heard about what happened next is curious but telling. The Chinese representative at the meeting is alleged to have said something like, “You won’t like what we are going to do next as a result of this.” Two weeks after the conclusion of the IMF meeting, we then had the devaluation of China’s currency, which in the minds of some triggered the increased volatility and market sell-offs that we have seen since then.

I know many of you are saying, “Pshaw, the Chinese would never do anything as irrational as that for such silly reasons.” And if you think that dear reader, you have yet to understand the concept of “Face” and the importance that it plays in the Asian world. You also do not understand the Chinese view of self – that they are a Great People and a Great Nation. And, that we disrespect them at our own peril. If you factor in a definition of long-term, measured in centuries, events become much more understandable.

I know many of you are saying, “Pshaw, the Chinese would never do anything as irrational as that for such silly reasons.” And if you think that dear reader, you have yet to understand the concept of “Face” and the importance that it plays in the Asian world. You also do not understand the Chinese view of self – that they are a Great People and a Great Nation. And, that we disrespect them at our own peril. If you factor in a definition of long-term, measured in centuries, events become much more understandable.

One must read the world financial press regularly to truly get a picture of global events. I suggest the Financial Times as one easily accessible source. What is reported and considered front page news overseas is very different from what is reported here. It seems on occasion that the bobble-heads who used to write for Pravda have gotten jobs in public relations and journalism in Washington and Wall Street.

One example – this week the Financial Times reported the story that many of the sovereign wealth funds (those funds established by countries such as Kuwait, Norway, and Singapore to invest in stocks, bonds, and other assets, for pension, infrastructure or healthcare, among other things), have been liquidating investments. And in particular, they have been liquidating stocks, not bonds. Another story making the rounds in Europe is that the various “Quantitative Easing” programs that we have seen in the U.S., Europe, and Japan, are, surprise, having the effect of being deflationary. And in the United States, we have recently seen the three month U.S. Treasury Bill trading at negative yields, the ultimate deflationary sign. Another story that is making the rounds – the Chinese have been selling their U.S. Treasury holdings and at a fairly rapid clip. This may cause an unscripted rate rise not intended or dictated by the Federal Reserve, but rather caused by market forces as the U.S. Treasury continues to come to market with refinancing issues.

One example – this week the Financial Times reported the story that many of the sovereign wealth funds (those funds established by countries such as Kuwait, Norway, and Singapore to invest in stocks, bonds, and other assets, for pension, infrastructure or healthcare, among other things), have been liquidating investments. And in particular, they have been liquidating stocks, not bonds. Another story making the rounds in Europe is that the various “Quantitative Easing” programs that we have seen in the U.S., Europe, and Japan, are, surprise, having the effect of being deflationary. And in the United States, we have recently seen the three month U.S. Treasury Bill trading at negative yields, the ultimate deflationary sign. Another story that is making the rounds – the Chinese have been selling their U.S. Treasury holdings and at a fairly rapid clip. This may cause an unscripted rate rise not intended or dictated by the Federal Reserve, but rather caused by market forces as the U.S. Treasury continues to come to market with refinancing issues.

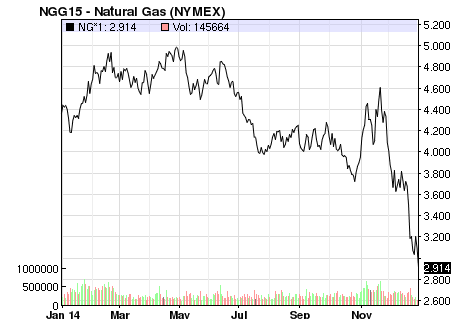

The collapse in commodity prices, especially oil, will sooner or later cause corporate bodies to float to the surface, especially in the energy sector. Counter-party (the other side of a trade) risk in hedging and lending will be a factor again, as banks start shrinking or pulling lines of credit. Liquidity, which was an issue long before this in the stock and bond markets (especially high yield), will be an even greater problem now.

The SEC, in response to warnings from the IMF and the Federal Reserve, has unanimously (which does not often happen) called for rules to prevent investors’ demands for redemptions in a market crisis from causing mutual funds to be driven out of business. Translation: don’t expect to get your money as quickly as you thought. I refer you to the SEC’s Proposal on Liquidity Risk Management Programs.

I mention that for the better of those who think that my repeated discussions of liquidity risk is “crying wolf.”

“It’s a Fine Kettle of Fish You’ve Gotten Us in, Ollie.”

I have a friend who is a retired partner from Wellington in Boston (actually I have a number of friends who are retired partners from there). Wellington is not unique in that, like Fidelity, it is very unusual for an analyst or money manager to stay much beyond the age of fifty-five.

So I asked him one day how he had his retirement investments structured, hoping I might get some perspective into thinking on the East Coast, as well as perhaps some insights into Vanguard’s products, given the close relationship between Vanguard and Wellington. His answer surprised me – “I have it all in index funds.” I asked if there were any particular index funds. Again the answer surprised me. “No bond funds, and actually only one index fund – the Vanguard S&P 500 Index Fund.” And when I asked for further color on that, the answer I got was that he was not in the business full time anymore, looking at markets and security valuations every day, so this was the best way to manage his retirement portfolio for the long-term at the lowest cost. Did he know that there were managers, that 10% or so, who consistently (or at least for a while, consistently) outperform the index? Yes, he was aware that such managers were out there. But at this juncture in his life he did not think that he either (a) had the time, interest, and energy to devote to researching and in effect “trading managers” by trading funds and (b) did not think he had any special skill set or insights that would add value in that process that would justify the time, the one resource he could not replace. Rather, he knew what equity exposure he wanted over the next twenty or thirty years (and he recognized that life expectancies keep lengthening). The index fund over that period of time would probably compound at 8% a year as it had historically with minimal transaction costs and minimal tax consequences. He could meet his needs for a diversified portfolio of equities at an expense ratio of five basis points. The rest of his assets would be in cash or cash equivalents (again, not bonds but rather insured certificates of deposit).

I have talked in the past about the need to focus on asset allocation as one gets older, and how index funds are the low cost way to achieve asset diversification. I have also talked about how your significant other may not have the same interest or ability in managing investments (trading funds) after you go on to your just reward. But I have not talked about the intangible benefits from investing in an index fund. They lessen or eliminate the danger of portfolio manager or analyst hubris blowing up a fund portfolio with a torpedo stock. They also eliminate the divergence of interests between the investment firm and investors that arises when the primary focus is running the investment business (gathering assets).

What goes into the index is determined not by the entity running the fund (although they can choose to create their own index, as some of the European banks have done, and charge fees close to 2.00%). There is no line drawn in the sand because a portfolio manager has staked his public reputation on his or her genius in investing in a particular entity. There is also no danger in an analyst recommending sale of an issue to lock in a bonus. There is no danger of an analyst recommending an investment to please someone in management with a different agenda. There is no danger of having a truncated universe of opportunities to invest in because the portfolio manager has a bias against investing in companies that have women chief executive officers. There is no danger of stock selection being tainted because a firm has changed its process by adding an undisclosed subjective screening mechanism before new ideas may be even considered. While firm insiders may know these things, it is a very difficult thing to learn them from the outside.

Is there a real life example here? I go back to the lunch I had at the time of the Morningstar Conference in June with the father-son team running a value fund out of Seattle. As is often the case, a subject that came up (not raised by me) was Washington Mutual (WaMu, a bank holding company that collapsed in 2008, trashing a bunch of mutual funds when it did). They opined how, by being in Seattle (a big small town), they had been able to observe up close and personally how the roll-up (which was what Washington Mutual was) had worked until it didn’t. Their observation was that the Old Guard, who had been at the firm from the beginning with the chair of the board/CEO had been able to remind him that he put his pants on one leg at a time. When that Old Guard retired over time, there was no one left who had the guts to perform that function, and ultimately the firm got too big relative to what had driven past success. Their assumption was that their Seattle presence gave them an edge in seeing that. Sadly, that was not necessarily the case. In the case of many an investment firm, Washington Mutual became their Stalingrad. Generally, less is more in investing. If it takes more than a few simple declarative sentences to explain why you are investing in a business, you probably should not be doing it. And when the rationale for investing changes and lengthens over time, it should serve as a warning.

I suspect many of you feel that the investment world is not this way in reality. For those who are willing to consider whether they should rein in their animal spirits, I commend to you an article entitled “Journey into the Whirlwind: Graham-and-Doddsville Revisited” by Louis Lowenstein (2006) and published by The Center for Law and Economic Studies at Columbia Law School. (Lowenstein, father of Roger Lowenstein, looks at the antics of large growth managers and conclude, “Having attracted, not investors, but speculators trying to catch the next new thing, management got the shareholders they deserved.” Snowball). When I look at the investment management profession today, as well as its lobbying efforts to prevent the imposition of stricter fiduciary standards, I question whether what they really feel in their hearts is that the sin of Madoff was getting caught.

The End

Is there anything I am going to say this month that may be useful to the long-term investor? There is at present much fear abroad in the land about investing in emerging and frontier markets today, driven by what has happened in China and the attendant ripple effect.

The question I will pose for your consideration is this. What if five years from now it becomes compellingly obvious that China has become the dominant economic force in the world? Since economic power ultimately leads to political and military power, China wins. How should one be investing a slice of one’s assets (actively-managed of course) today if one even thinks that this is a remotely possible outcome? Should you be looking for a long-term oriented, China-centric fund?

There is one other investment suggestion I will make that may be useful to the long-term investor. David has raised it once already, and that is dedicating some assets into the micro-cap stock area. Focus on those investments that are in effect too small and extraordinarily illiquid in market capitalization for the big firms (or sovereign wealth funds) to invest in and distort the prices, both coming and going. Micro-cap investing is an area where it is possible to add value by active management, especially where the manager is prepared to cap the assets that it will take under management. Look for managers or funds where the strategy cannot be replicated or imitated by an exchange traded fund. Always remember, when the elephants start to dance, it is generally not pleasant for those who are not elephants.

Edward A. Studzinski

P.S. – Where Eagles Dare

The fearless financial writer for the New York Times, Gretchen Morgenson, wrote a piece in the Sunday Times (9/27/2015) about the asset management company First Eagle Investment Management. The article covered an action brought by the SEC for allegedly questionable marketing practices under the firm’s mutual funds’ 12b-1 Plan. Without confirming or denying the allegations, First Eagle settled the matter by paying $27M in disgorgement and interest, and $12.5M in fines. With approximately $100B in assets generating an estimated $900+M in revenues annually, one does not need to hold a Tag Day for the family-controlled firm. Others have written and will write more about this event than I will.

Of more interest is the fact that Blackstone Management Partners is reportedly purchasing a 25% stake in First Eagle that is being sold by T/A Associates of Boston, another private equity firm. As we have seen with Matthews in San Francisco, investments in investment management firms by private equity firms have generally not inured to the benefit of individual investors. It remains to be seen what the purpose is of this investment for Blackstone. Blackstone had had a right-time, right-strategy investment operation with its two previously-owned closed-end funds, The Asia Tigers Fund and The India Fund, both run by experienced teams. The funds were sold to Aberdeen Asset Management, ostensibly so Blackstone could concentrate on asset management in alternatives and private equity. With this action, they appear to be rethinking that.

Other private equity firms, like Oaktree, have recently launched their own specialist mutual funds. I would note however that while the First Eagle Funds have distinguished long-term records, they were generated by individuals now absent from the firm. There is also the question of asset bloat. One has to wonder if the investment strategy and methodology could not be replicated by a much lower cost (to investors) vehicle as the funds become more commodity-like.

Which leaves us with the issue of distribution – is a load-based product, going through a network of financial intermediaries, viable, especially given how the Millennials appear to make their financial decisions? It remains to be seen. I suggest an analogy worth considering is the problem of agency-driven insurance firms like Allstate. Allstate would clearly like to not have an agency distribution system, and would make the switch overnight if it could without losing business. It can’t, because too much of the book of business would leave. And yet, when one looks at the success of GEICO and Progressive in going the on-line or 1-800 route, one can see the competitive disadvantage, especially in automobile insurance, which is the far more profitable business to capture. It remains to be seen how distribution will evolve in the investment management world, especially as pertains to funds. As fiduciary requirements change, there is the danger of the entire industry model also changing.

Why Vanguard Will Take Over the World

By Sam Lee, principal of Severian Asset Management and former editor of Morningstar ETF Investor.

Vanguard is eating everything. It is the biggest fund company in the U.S., with over $3 trillion in assets under management as of June-end, and the second biggest asset manager in the world, after BlackRock. Size hasn’t hampered Vanguard’s growth. According to Morningstar, Vanguard took in an estimated $166 billion in U.S. ETF and mutual fund assets in the year-to-date ending in August, over three times the next closest company, BlackRock/iShares. Not only do I think Vanguard will eventually overtake BlackRock, it will eventually extend its lead to become by far the most dominant asset manager in the world.

With index funds, investors mostly care about having their desired exposure at the lowest all-in cost, the most visible component of which is the expense ratio. In other words, index funds are commodities. In a commodity industry with economies of scale, the lowest-cost producer crushes the competition. Vanguard is the lowest-cost producer. Not only that, it enjoys a first-mover advantage and possesses arguably the most trusted brand in asset management. These advantages all feed on each other in virtuous cycles.

It’s commonly known Vanguard is owned by its mutual funds, so everything is run “at cost.” (This is a bit of a fiction; some Vanguard funds subsidize others or outside ventures.) “Profits” flow back to the funds as lower expense ratios. There are no external shareholders to please, no quarterly earnings targets to hit. Many cite this as the main reason why Vanguard has been so successful. However, the mutual ownership structure has not always led to lower all-in costs or dominance in other industries, such as insurance, or even in asset management. Mutual ownership is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for Vanguard’s success.

What separates Vanguard from other mutually owned firms is that it operates in a business that benefits from strong first-mover advantages. By being the first company to offer index funds widely, it achieved a critical mass of assets and name recognition before anyone else. Assets begot lower fees which begot even more assets, a cycle that still operates today.

While Vanguard locked up the index mutual fund market, it almost lost its leadership by being slow to launch exchange-traded funds. By the time Vanguard launched its first in 2001, State Street and Barclays already had big, widely traded ETFs covering most of the major asset classes. While CEO and later chairman of the board, founder Jack Bogle was opposed to launching ETFs. He thought the intraday trading ETFs allowed would be the rope by which investors hung themselves. From a pure growth perspective, this was a major unforced error. The mistake was reversed by his successor, Jack Brennan, after Bogle was effectively forced into retirement in 1999.

In ETFs, the first-movers not only enjoy economies of scale but also liquidity advantages that allows them to remain dominant even when their fees aren’t the lowest. When given the choice between a slightly cheaper ETF with low trading volume and a more expensive ETF with high trading volume, most investors go with the more traded fund. Because ETFs attract a lot of traders, the expense ratio is small in comparison to cost of trading. This makes it very difficult for new ETFs to gain traction when an established fund has ample trading volume. The first U.S. ETF, SPDR S&P 500 ETF SPY, remains the biggest and most widely traded. In general, the biggest ETFs were also the first to come out in their respective categories. The notable exceptions are where Vanguard ETFs managed to muscle their way to the top. Despite this late start, Vanguard has clawed its way up to become the second largest ETF sponsor in the U.S.

This feat deserves closer examination. If Vanguard’s success in this area was due to one-off factors such as the tactical cleverness of its managers or missteps by competitors, then we can’t be confident that Vanguard will overtake entrenched players in other parts of the money business. But if it was due to widely applicable advantages, then we can be more confident that Vanguard can make headway against entrenched businesses.

A one-off factor that allowed Vanguard to take on its competitors was its patented hub and spoke ETF structure, where the ETF is simply a share class of a mutual fund. By allowing fund investors to convert mutual fund shares into lower-cost ETF shares (but not the other way around), Vanguard created its own critical mass of assets and trading volume.

But even without the patent, Vanguard still would have clawed its way to the top, because Vanguard has one of the most powerful brands in investing. Whenever someone extols the virtues of index funds, they are also extoling Vanguard’s. The tight link was established by Vanguard’s early dominance of the industry and a culture that places the wellbeing of the investor at the apex. Sometimes this devotion to the investor manifests as a stifling paternalism, where hot funds are closed off and “needless” trading is discouraged by a system of fees and restrictions. But, overall, Vanguard’s culture of stewardship has created intense feelings of goodwill and loyalty to the brand. No other fund company has as many devotees, some of whom have gone as far as to create an Internet subculture named after Bogle.

Over time, Vanguard’s brand will grow even stronger. Among novice investors, Vanguard is slowly becoming the default option. Go to any random forum where investing novices ask how they should invest their savings. Chances are good at least someone will say invest in passive funds, specifically ones from Vanguard.

Vanguard is putting its powerful brand to good use by establishing new lines of business in recent years. Among the most promising in the U.S. is Vanguard Personal Advisor Services, a hybrid robo-advisor that combines largely automated online advice with some human contact and intervention. VPAS is a bigger deal than Vanguard’s understated advertising would have you believe. VPAS effectively acts like an “index” for the financial advice business. Why go with some random Edward Jones or Raymond James schmuck who charges 1% or more when you can go with Vanguard and get advice that will almost guarantee a superior result over the long run?

VPAS’s growth has been explosive. After two years in beta, VPAS had over $10 billion by the end of 2014. By June-end it had around $22 billion, with about $10 billion of that growth from the transfer of assets from Vanguard’s traditional financial advisory unit. This already makes Vanguard one of the biggest and fastest growing registered investment advisors in the nation. It dwarfs start-up robo-advisors Betterment and Wealthfront, which have around $2.5 billion and $2.6 billion in assets, respectively.

Abroad, Vanguard’s growth opportunities look even better. Passive management’s market share is still in the single digits in many markets and the margins from asset management are even fatter. Vanguard has established subsidiaries in Australia, Canada, Europe and Hong Kong. They are among the fastest-growing asset managers in their markets.

The arithmetic of active management means over time Vanguard’s passive funds will outperform active investors as a whole. Vanguard’s cost advantages are so big in some markets its funds are among the top performers.

Critics like James Grant, editor of Grant’s Interest Rate Observer, think passive investing is too popular. Grant argues investing theories operate in cycles, where a good idea transforms into a fad that inevitably collapses under its own weight. But passive investing is special. Its capacity is practically unlimited. The theoretical limit is the point at which markets become so inefficient that price discovery is impaired and it becomes feasible for a large subset of skilled retail investors to outperform (the less skilled investors would lose even more money more quickly in such an environment—the arithmetic of active management demands it). However, passive investing can make markets more efficient if investors opting for index funds are largely novices rather than highly trained professionals. A poker game with fewer patsies means the pros have to compete with each other.

There are some problems with passive investing. Regularities in assets flows due to index-based buying and selling has created profit opportunities for clever traders. Stocks added to and deleted from the S&P 500 and Russell 2000 indexes experience huge volumes of price-insensitive trading driven by dumb, blind index funds. But these problems can be solved by smart fund management, better index construction (for example, total market indexes) or greater diversity in commonly followed indexes.

Why Vanguard May Not Take Over the World

I’m not imaginative or smart enough to think of all the reasons why Vanguard will fail in its global conquest, but a few risks pop out.

First is Vanguard’s relative weakness in institutional money management (I may be wrong on this point). BlackRock is still top dog thanks to its fantastic institutional business. Vanguard hasn’t ground BlackRock into dust because expense ratios for institutional passively managed portfolios approach zero. Successful asset gatherers offer ancillary services and are better at communicating with and servicing the key decision makers. BlackRock pays more and presumably has better salespeople. Vanguard is tight with money and so may not be willing or able to hire the best salespeople.

Second, Vanguard may make a series of strategic blunders under a bad CEO enabled by an incompetent and servile board. I have the greatest respect for Bill McNabb and Vanguard’s current board, but it’s possible his successors and future boards could be terrible.

Third, Vanguard may be corrupted by insiders. There is a long and sad history of well-meaning organizations that are transformed into personal piggybanks for the chief executive officer and his cronies. Signs of corruption include massive payouts to insiders and directors, a reversal of Vanguard’s long-standing pattern of lowering fees, expensive acquisitions or projects that fuel growth but do little to lower fees for current investors (for example, a huge ramp up in marketing expenditures), and actions that boost growth in the short-run at the expense of Vanguard’s brand.

Fourth, Vanguard may experience a severe operational failure, such as a cybersecurity hack, that damages its reputation or financial capacity.

Individually and in total, these risks seem manageable and remote to me. But I could be wrong.

Summary

- Vanguard’s rapid growth will continue for years as it benefits from three mutually reinforcing advantages: mutual ownership structure where profits flow back to fund investors in the form of lower expenses, first-mover advantage in index funds, and a powerful brand cultivated by a culture that places the investor first.

- Future growth markets are huge: Vanguard has subsidiaries in Australia, Canada, Hong Kong and Europe. These markets are much less competitive than the U.S., have higher fees and lower penetration of passive investing. Arithmetic of active investing virtually guarantees Vanguard funds will have a superior performance record over time.

- Vanguard Personal Advisor Services VPAS stands a good chance of becoming the “index” for financial advice. Due to fee advantages and brand, VPAS may be able to replicate the runaway growth Vanguard is experiencing in ETFs.

- Limits to passive investing are overblown; Vanguard still has lots of runway.

- Vanguard may wreck its campaign of global domination through several ways, including lagging in institutional money management, incompetence, corruption, or operational failure.

Needles, haystacks and grails

By Leigh Walzer, principal of Trapezoid LLC.

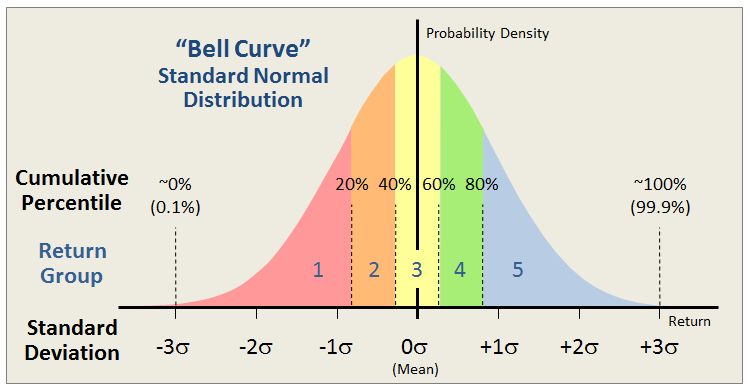

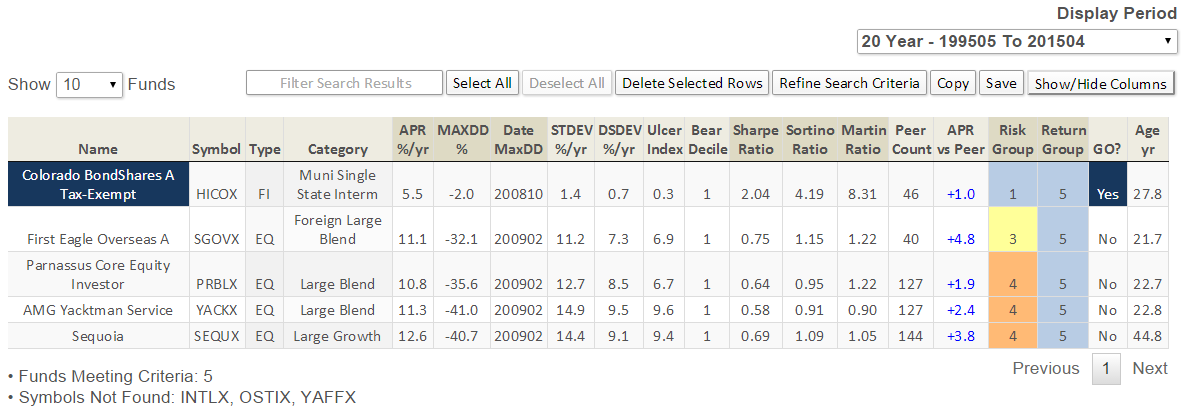

The Holy Grail of mutual fund selection is predictive validity. In other words, does a positive rating today predict exceptional performance in the future? Jason Zweig of The Wall Street Journal recently cited an S&P study which found three quarters of active mutual funds fail to beat their benchmark over the long haul.

We believe it’s possible, with a reasonable degree of predictive validity, to identify the likelihood a manager will succeed in the future. Trapezoid’s Orthogonal Attribution Engine (OAE) searches for the proverbial needles in a haystack: portfolio managers who exhibit predictable skill, and particularly those who justify based on a statistical analysis paying the higher freight of an active fund. In today’s case only 1 fund has predictable skill, and none justify their expenses. In general fewer than 5% of funds meet our criteria.

We believe it’s possible, with a reasonable degree of predictive validity, to identify the likelihood a manager will succeed in the future. Trapezoid’s Orthogonal Attribution Engine (OAE) searches for the proverbial needles in a haystack: portfolio managers who exhibit predictable skill, and particularly those who justify based on a statistical analysis paying the higher freight of an active fund. In today’s case only 1 fund has predictable skill, and none justify their expenses. In general fewer than 5% of funds meet our criteria.

One of our premises is that managers who made smart decisions in the past tend to continue and vice versa. We try to break out the different types of decisions that managers have to make (e.g., selecting individual securities, sectors to overweight or currency exposure to avoid). Our system works well based on “back testing;” that is, sitting here in 2015, constructing models of what funds looked like in the past and then seeing if we could predict forward. We have published the results of back-testing, available on our website. (Go to www.fundattribution.com, demo registration required, free to MFO readers.) Using data through July 2014, historical stock-picking skill predicted skill for the subsequent 12 months with 95% confidence. Performance over the past 5 years received the most weight but longer term results (when available) were also very important. We got similar results predicting sector-rotation skills. We repeated the tests using data through July 2013 and got nearly identical results.

We are also publishing forward looking predictions (for large blend funds) to demonstrate this point.

The hard part is measuring skill accurately. The key is to analyze portfolio weightings and characteristics over time. We derive this using both historic funds holdings data and regression/inference, supported by data on individual securities.

Here’s your challenge: you need to decide how high the chances of success need to be to justify choosing a higher-cost option in your portfolio. Should managers with great track records command a higher fee? Yes, with caveats. Although the statistical relationship is solid, skill predictions tend to be fairly conservative. This is a function of the inherent uncertainty about what the future will bring.

The confidence band around individual predictions is fairly wide. The noise level varies: some funds have longer and richer history, more consistent display of skill, longer manager tenure, better data, etc. The less certain we are the past will repeat, the less we should be willing to pay a manager with a great track record. In theory we might be willing to hire a manager if we have 51% confidence he will justify his fees, but investors may want a margin of safety.

Let’s look at some concrete examples of what that means. We are going to illustrate this month with utility funds. Readers who register at the FundAttribution website will be able to query individual funds and access other data. I do not own any of the funds discussed in this piece

Active utility funds are coming off a tough year. The average fund returned only 2.2% in the year ending July 31, 2015; that’s signaled by the “gross return” for the composite at the bottom of the fourth column. Expenses consumed more than half of that. This sector has faced heavy redemptions which may intensify as the Fed begins to taper.

FundAttribution tracks 15 active utility funds. (We also follow 2 rules-based funds and 30 active energy infrastructure funds.) We informally cluster them into three groups:

TABLE 1: Active Utility Funds. Data as of July 31, 2015

| Annualized Skill (%) | |||||||

| AUM | Tenure (Yrs) | Gross Rtn % | 1 yr | 3 yr | 5 yr | Predict* | |

| Conservative | |||||||

| Franklin Utilities | 5,200 | 17 | 6.9 | 0.3 | -4.0 | -1.4 | -0.2 |

| Fidelity Select Utilities | 700 | 9 | 3.0 | -6.4 | -5.1 | -2.9 | -1.2 |

| Wells Fargo Utility & Telecom | 500 | 13 | 4.4 | -2.5 | -4.4 | -1.3 | -0.6 |

| American Century Utilities | 400 | 5 | 5.9 | -0.6 | -5.6 | -0.7 | |

| Rydex Utilities | 100 | 15 | 7.0 | 0.6 | -5.3 | -3.2 | -0.8 |

| Reaves Utilities & Energy Infr. | 70 | 10 | -1.3 | -4.7 | -3.2 | -1.4 | -0.5 |

| ICON Utilities | 20 | 10 | 7.1 | -0.8 | -4.8 | -2.8 | -0.7 |

| 6.2 | -0.6 | -4.2 | -1.5 | ||||

| Moderate | |||||||

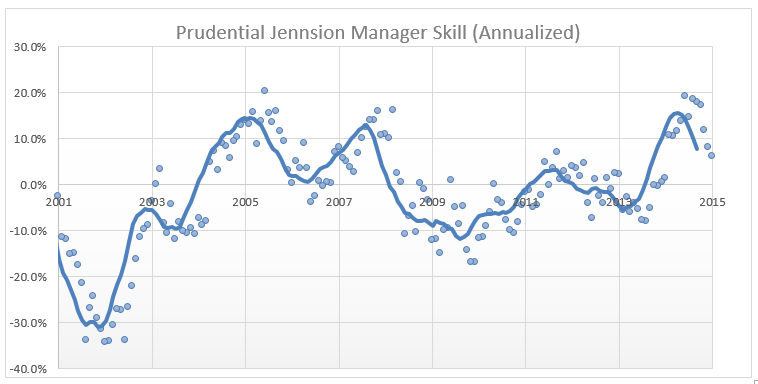

| Prudential Jennison Utility | 3,200 | 15 | 2.9 | -1.7 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| Gabelli Utilities | 2,100 | 16 | -1.0 | -7.9 | -5.5 | -3.8 | -1.4 |

| Fidelity Telecom & Utilities | 900 | 10 | 3.0 | -4.7 | -2.8 | 1.2 | -1.0 |

| John Hancock Utilities | 400 | 14 | 0.9 | -5.3 | 1.4 | -1.1 | -0.7 |

| Putnam Global Utilities | 200 | 15 | 1.6 | -3.3 | -4.1 | -3.8 | -1.2 |

| Frontier MFG Core Infr. | 100 | 3 | 2.6 | -3.0 | -1.0 | -0.4 | |

| 1.5 | -4.3 | -1.7 | -1.0 | ||||

| Aggressive | |||||||

| MFS Utilities | 5,200 | 20 | 1.2 | -4.2 | -2.1 | 2.0 | -0.9 |

| Duff & Phelps Global Utility Income | 800 | 4 | -13.8 | -18.0 | -7.3 | -0.8 | |

| -1.2 | -6.5 | -2.9 | 1.6 | ||||

| Composite | 2.2 | -3.7 | -2.9 | -0.3 | -0.5 | ||

*”Predict” is our extrapolation of skill for the 12 months ending July 2016

The Conservative funds tend to stick to their knitting with 70-90% exposure to traditional utilities, <10% foreign exposure, and beta of under 60%. The Aggressive funds are the most adventurous in pursuing related industries and foreign stocks; their beta is 85% (boosted for Duff & Phelps by leverage).

Without being too technical, the OAE determines a target return for each fund each period based on all its characteristics. The difference between gross return and the target equals skill. Skill can be further decomposed into components (e.g. sector selection (sR) vs security selection (sS.) For today’s discussion skill will mean the combination of sR and sS. Here’s how to read the table above: the managers at Franklin Utilities – a huge Morningstar “gold” fund – did slightly better than a passive manager over the past year (before expenses) and underperformed for the past three and five years. We anticipate that they’re going to slightly underperform a passive alternative in the year ahead. That’s better than our system predicts for, say, Fidelity, Putnam or Gabelli but it’s still no reason to celebrate.

In the aggregate these funds have below average beta, moderate non-US exposure, value tilt and a slight midcap bias. The OAE’s target return for the sector over the last year is 6.3%, so the basket of active utility funds had skill of-3.7%. Only two of the 15 funds had positive skill. Negative overall skill means that investors could have chosen other sectors with similar characteristics which produced better returns.

The 2014 energy shock was a major contributing factor. These funds allocated on average only 60-70% to regulated electric and gas generation and distribution. Much of the balance went to Midstream Energy, Merchant Power, Exploration & Production, and Telecom. Those decisions explain most of the difference among funds. Funds which stayed close to home (Icon, Franklin, Rydex, and Putnam) navigated this environment best.

Security selection moved the needle at a few funds. Prudential Jennison stuck to S&P500 components but did a good job overweighting winners. Duff & Phelps had some dreadful performers in its non-utility portfolio.

Skill last year for the two Fidelity funds was impacted by volatile returns which may reflect increased risk-taking.

We use the historic skill to predict next year’s skill. Success over the past 5 years carries the most weight, but we look at managers’ track record, consistency, and trends over their entire tenure.

The predicted skill for next year falls within a relatively tight range: Prudential has the highest skill at 0.8%, Gabelli has the lowest at -1.4%. Either the difference between best and worst in this sector is not that great or our model is not sufficiently clairvoyant.

Either way, these findings don’t excite us to pay 120bps, which is the typical expense ratio in this sector. The OAE rates the probability a fund’s skill this year will justify the freight. Cost in the chart below is the differential between the expense ratio of a fund class and the ~15bp you would pay for a passive utility fund. This analysis varies by share class, the table below shows one representative class for each fund.

We look for funds with a probability of at least 60%, and (as shown in Table 2) none of the active funds here come close. Here’s how to read the table: our system predicts that Franklin Utilities will underperform by 0.2% over the next 12 years but that number is the center of a probable performance band that’s fairly wide, so it could outperform over the next year. Given its expenses of 60 basis points, how likely are they to pull it off? They have about a 40% chance of it to which we’d say, “not good enough.”

TABLE 2

| Name | Ticker | Predict | Std Err | Cost | Prob | Stars |

| Conservative | ||||||

| Franklin Utilities | FKUTX | -0.2% | 3.2% | 0.60% | 41% | 3 |

| Fidelity Select Utilities | FSUTX | -1.2% | 3.3% | 0.65% | 29% | 3 |

| Wells Fargo Utility & Telecom | EVUAX | -0.6% | 2.6% | 0.99% | 27% | 3 |

| American Century Utilities | BULIX | -0.7% | 2.9% | 0.52% | 33% | 3 |

| Rydex Utilities | RYAUX | -0.8% | 2.7% | 1.73% | 17% | 2 |

| Reaves Utilities & Energy Infrastructure | RSRAX | -0.5% | 2.0% | 1.40% | 18% | 2 |

| ICON Utilities | ICTUX | -0.7% | 2.8% | 1.35% | 24% | 2 |

| Moderate | ||||||

| Prudential Jennison Utility | PCUFX | 0.8% | 2.3% | 1.40% | 40% | 3 |

| Gabelli Utilities | GABUX | -1.4% | 2.6% | 1.22% | 15% | 3 |

| Fidelity Telecom & Utilities | FIUIX | -1.0% | 2.6% | 0.61% | 26% | 4 |

| John Hancock Utilities | JEUTX | -0.7% | 2.3% | 0.80% | 26% | 5 |

| Putnam Global Utilities | PUGIX | -1.2% | 2.6% | 1.06% | 20% | 1 |

| Frontier MFG Core Infrastructure | FMGIX | -0.4% | 2.3% | 0.55% | 34% | 4 |

| Aggressive | ||||||

| MFS Utilities | MMUCX | -0.9% | 2.8% | 1.61% | 19% | 4 |

| Duff & Phelps Global Utility Income | DPG | -0.8% | 2.5% | 1.11% | 23% | 2 |

The bottom line: We can’t recommend any of these funds. Franklin might be the least bad choice based on its low fees. Prudential Jennison (PCUFX) has shown flashes of replicable stock picking skill; they would be more competitive if they reduced fees.

Duff & Phelps (DPG) merits consideration. At press time this closed end fund trades at a 15% discount to NAV. This is arguably more than required to compensate investors for the high expenses. The fund is more growth-oriented than the peer group, runs leverage of 1.28x, and maintains significant foreign exposure. There is a 9% “dividend yield;” however, performance last year and over time was dreadful, the dividend does not appear sustainable, and the prospect of rising rates adds to the negative sentiment. So, the timing may not be right.

We show the Morningstar ratings of these funds for comparison. We don’t grade on a curve and from our perspective none of the funds deserve more than 3 stars. Investors looking for such exposure might improve their odds by buying and holding Vanguard Utilities ETF (VPU) with its 0.12% expense ratio or Utilities Select Sector SPDR (XLU)

It is hard for active utility funds to generate enough skill to justify their cost structure. The conservative funds have more or less matched passive indices, so why pay an extra 60 bps. The funds which took on more risk have a mixed record, and their fee structures tend to be even higher.

Perhaps the industry has recognized this: outflows from actively-managed utility funds have accelerated to double digits over the past 2.5 years and the share of market held by passive funds has increased steadily. A number of industry players have repositioned their utility funds as dividend income funds or merged them into other strategies.

Next month: we will apply the same techniques to large blend funds where we hope to find a few active managers worthy of your attention

Investors who want a sneak preview (of the predicted skill by fund) can register at www.fundattribution.com and click the link near the bottom of the Dashboard page.

Your feedback is welcome at [email protected].

Top developments in fund industry litigation

![]() Fundfox, launched in 2012, is the mutual fund industry’s only litigation intelligence service, delivering exclusive litigation information and real-time case documents neatly organized, searchable, and filtered as never before. For the complete list of developments last month, and for information and court documents in any case, log in at www.fundfox.com and navigate to Fundfox Insider.

Fundfox, launched in 2012, is the mutual fund industry’s only litigation intelligence service, delivering exclusive litigation information and real-time case documents neatly organized, searchable, and filtered as never before. For the complete list of developments last month, and for information and court documents in any case, log in at www.fundfox.com and navigate to Fundfox Insider.

Orders

- In the first case brought under the agency’s distribution-in-guise initiative, the SEC charged First Eagle and its affiliated fund distributor with improperly using mutual fund assets to pay for the marketing and distribution of fund shares. (In re First Eagle Inv. Mgmt., LLC.)

- In the purported class action by direct investors in Northern Trust‘s securities lending program, the court struck defendants’ motion for summary judgment without prejudice. (La. Firefighters’ Ret. Sys. v. N. Trust Invs., N.A.)

- Adopting a Magistrate Judge’s recommendation, a court granted Nuveen‘s motion to dismiss a securities fraud lawsuit regarding four closed-end bond funds affected by the 2008 collapse of the market for auction rate preferred securities. Defendants included the independent chair of the funds’ board. (Kastel v. Nuveen Invs. Inc.)

New Lawsuits

- Alleging the same fee claim but for a different damages period, plaintiffs filed a second “anniversary complaint” in the fee litigation regarding six Principal target-date funds. The litigation has previously survived defendants’ motion to dismiss. (Am. Chems. & Equip., Inc. 401(k) Ret. Plan v. Principal Mgmt. Corp.)

- Investment adviser Sterling Capital is among the defendants in a new ERISA class action that challenges the selection of proprietary funds for its parent company’s 401(k) plan. (Bowers v. BB&T Corp.)

Briefs

- Calamos filed a reply brief in support of its motion to dismiss fee litigation regarding its Growth Fund. (Chill v. Calamos Advisors LLC.)

- In the ERISA class action regarding Fidelity‘s practices with respect to “float income” generated from transactions in retirement plan accounts, plaintiffs filed their opening appellate brief in the First Circuit, seeking to reverse the district court decision granting Fidelity’s motion to dismiss. The U.S. Secretary of Labor filed an amicus brief in support of plaintiffs, arguing that ERISA prohibits fiduciaries from using undisclosed float income obtained through plan administration for any purpose other than to benefit the ERISA-covered plan. (Kelley v. Fid. Mgmt. Trust Co.)

The Alt Perspective: Commentary and news from DailyAlts

I think it would be safe to say that most of us are happy to see the third quarter come to an end. While a variety of issues clearly remain on the horizon, it somehow feels like the potholes of the past six weeks are a bit more distant and the more joyous holiday season is closing in. Or, it could just be cognitive biases on my part.

I think it would be safe to say that most of us are happy to see the third quarter come to an end. While a variety of issues clearly remain on the horizon, it somehow feels like the potholes of the past six weeks are a bit more distant and the more joyous holiday season is closing in. Or, it could just be cognitive biases on my part.

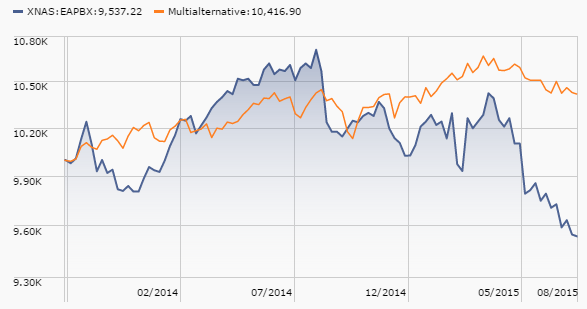

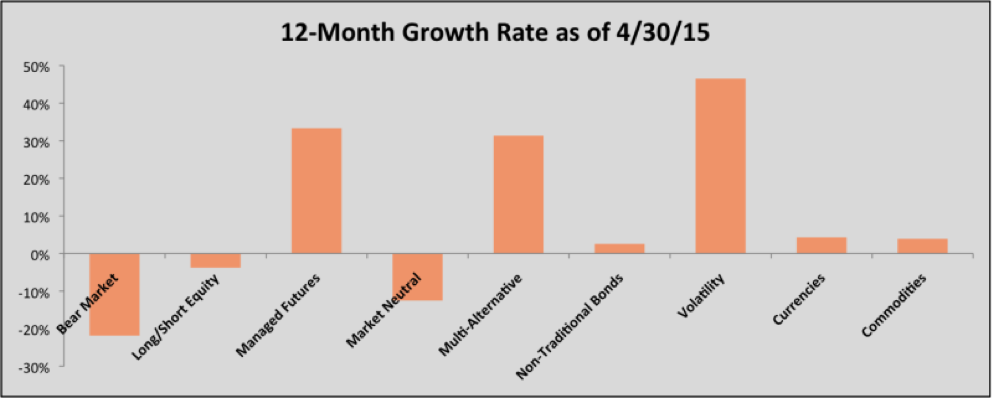

Either way, the numbers are in. Here is a look at the 3rd Quarter performance for both traditional and alternative mutual fund categories as reported by Morningstar.

- Large Blend U.S. Equity: -7.50%

- Foreign Equity Large Blend: -10.37

- Intermediate Term Bond: 0.32%

- World Bond: -1.22%

- Moderate Allocation: -5.59%

Anything with emerging markets suffered even more. Now a look at the liquid alternative categories:

- Long/Short Equity: -4.44

- Non-Traditional Bonds: -1.96%

- Managed Futures: 0.38%

- Market Neutral: -0.26

- Multi-Alternative: -3.05

- Bear Market: 13.05%

And a few non-traditional asset classes:

- Commodities: -14.38%

- Multi-Currency: -3.35%

- Real Estate: 1.36%

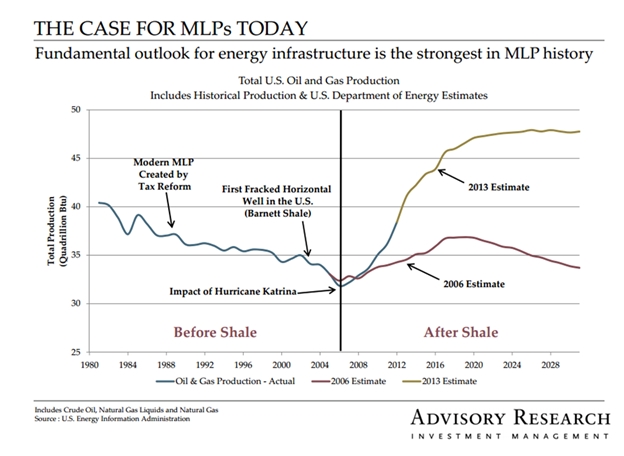

- Master Limited Partnerships: -25.73%

While some media reports have questioned the performance of liquid alternatives over the past quarter, or during the August market decline, they actually have performed as expected. Long/short funds outperformed their long-only counterparts, managed futures generated positive performance (albeit fairly small), market neutral funds look fairly neutral with only a small loss on the quarter, and multi-alternative funds outperformed their moderate allocation counterparts.

The one area in question is the non-traditional bond category where these funds underperformed both traditional domestic and global bond funds. Long exposure to riskier fixed income asset would certainly have hurt many of these funds.

Declining energy prices zapped both the commodities and master limited partnerships categories, both of which had double-digit losses. Surprisingly, real estate held up well and there is even talk of developers looking to buy-back REITs due to their low valuations.

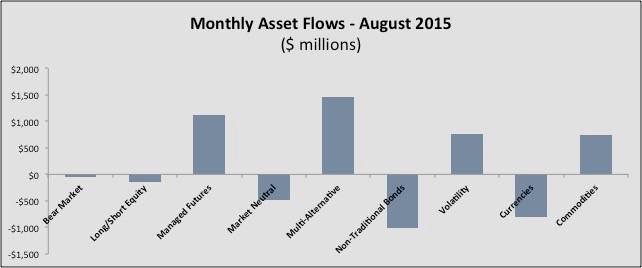

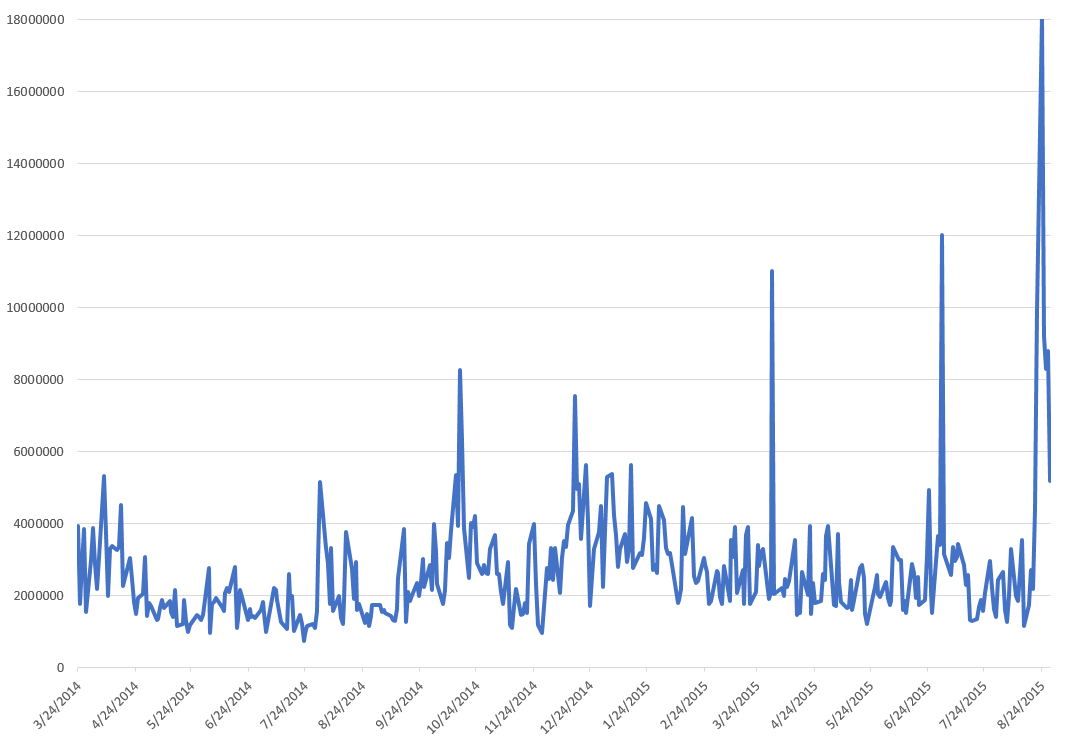

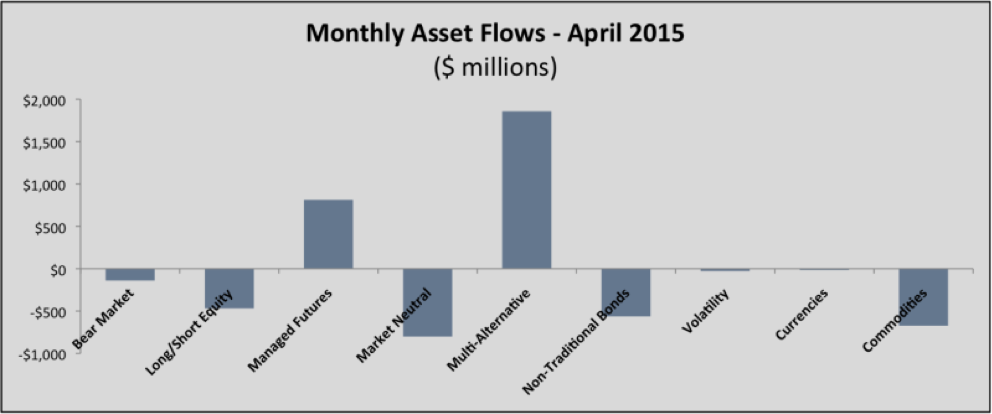

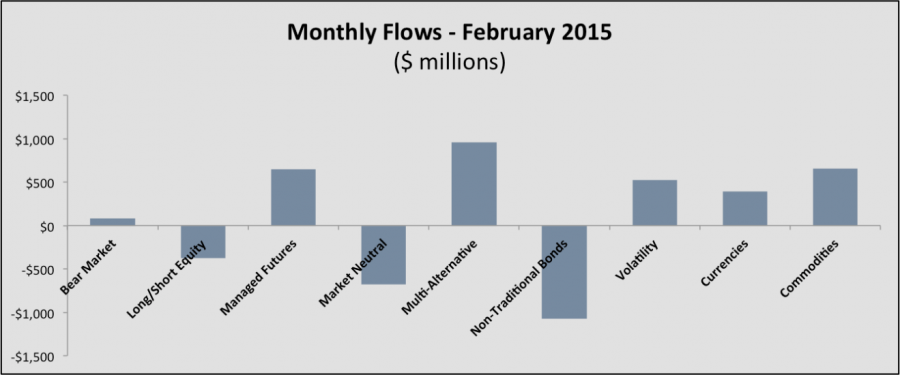

Let’s take a quick look at asset flows for August. Investors continued to pour money into managed futures funds and multi-alternative funds, the only two categories with positive inflows in every month of 2015. Volatility also got a boost in August as the CBOE Volatility Index spiked during the month. The final category to gather assets in August was commodities, surprisingly enough.

A few research papers of interest this past month:

PIMCO Examines How Liquid Alternatives Fit into Portfolios – this is a good primer on liquid alternatives with an explanation of how evaluated and use them in a portfolio.

The Path Forward for Women in Alternatives – this is an important paper that documents the success women have had in the alternative investment business. While there is much room for growth, having a study to outline the state of the current industry helps create more awareness and attention on the topic.

Investment Strategies for Tough Times – AQR provides a review of the 10 worst quarters for the market since 1972 and shows which investment strategies performed the best (and worst) in each of those quarters.

And finally, there were two regulatory topics that grabbed headlines this past month. The first was an investor alert issued by FINRA regarding “smart beta” product. Essentially, FINRA wanted to warn investors that not all smart beta products are alike, and that many different factors drive their returns. Essentially, buyer beware. The second was from the SEC who is proposing new liquidity rules for mutual funds and ETFs. One of the more pertinent rules is that having to do with maintain a three-day liquid asset minimum that would likely force many funds to hold more cash, or cash equivalents. This proposal is now in the 90-day comment period.

Have a great October and we will talk again (in this virtual way) just after Halloween! Let’s just hope the Fed doesn’t have any tricks up their sleeve in the meantime.

Elevator Talk: Michael Underhill, Capital Innovations Global Agri, Timber, Infrastructure Fund (INNAX)

Elevator Talk: Michael Underhill, Capital Innovations Global Agri, Timber, Infrastructure Fund (INNAX)

Since the number of funds we can cover in-depth is smaller than the number of funds worthy of in-depth coverage, we have decided to offer one or two managers each month the opportunity to make a 200 word pitch to you. That’s about the number of words a slightly-manic elevator companion could share in a minute and a half. In each case, I’ve promised to offer a quick capsule of the fund and a link back to the fund’s site. Other than that, they’ve got 200 words and precisely as much of your time and attention as you’re willing to share. These aren’t endorsements; they’re opportunities to learn more.

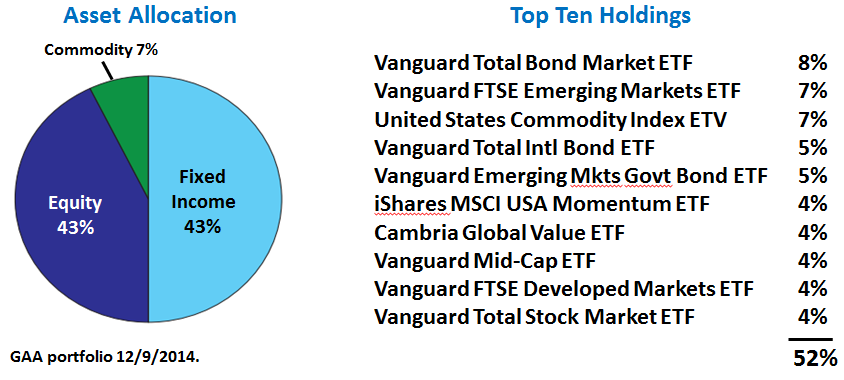

Michael Underhill manages INNAX, which launched at the end of September 2012. Mr. Underhill worked as a real asset portfolio manager for AllianceBernstein and INVESCO prior to founding Capital Innovations in 2007. He also manages about $170 million in this same strategy through separate accounts and four funds available only to Canadian investors.

Assets can be divided into two types: real and financial. Real assets are things you can touch: gold, oil, roads, bridges, soybeans, and lumber. Financial assets are intangible; stocks, for example, represent your hypothetical fractional ownership of a corporation and your theoretical claim to some portion of the value of future earnings.

Most individual portfolios are dominated by financial assets. Most institutional portfolios, however, hold a large slug of real assets and most academic research says that the slug should be even larger than it is.

Why so? Real assets possess four characteristics that are attractive and difficult to achieve.

They thrive in environments hostile to stocks and bonds. Real assets are positively correlated with inflation, stocks are weakly correlated with inflation and bonds are negatively correlated. That is, when inflation rises, bonds fall, stocks stall and real assets rise.

They are uncorrelated with the stock and bond markets. The correlation of returns for the various types of real assets hover somewhere just above or just below zero with relation to both the stock and bond market.

They are better long term prospects than stocks or bonds. Over the past 10- and 20-year periods, real assets have produced larger, steadier returns than either stocks or bonds. While it’s true that commodities have cratered of late, it’s possible to construct a real asset portfolio that’s not entirely driven by commodity prices.

A portfolio with real assets outperforms one without. The research here is conflicted. Almost everything we’ve read suggests that some allocation to real assets improves your risk-return profile. That is, a portfolio with real assets, stocks and bonds generates a greater return for each additional unit of risk than does a pure stock/bond portfolio. Various studies seem to suggest a more-or-less permanent real asset allocation of between 20-80% of your portfolio. I suspect that the research oversimplifies the situation since some of the returns were based on private or illiquid investments (that is, someone buying an entire forest) and the experience of such investments doesn’t perfectly mirror the performance of liquid, public investments.

Inflation is not an immediate threat but, as Mr. Underhill notes, “it’s a lot cheaper to buy an umbrella on a sunny day than it is once the rain starts.” Institutional investors, including government retirement plans and university endowments, seem to concur. Their stake in real assets is substantial (14-20% in many cases) and growing (their traditional stakes, like yours, were negligible).

INNAX has performed relatively well – in the top 20% of its natural resources peer group – over the past three years, aided by its lighter-than-normal energy stake. The fund is down about 5% since inception while its peers posted a 25% loss in the same period. The fund is fully invested, so its outperformance cannot be ascribed to sitting on the sidelines.

Here are Mr. Underhill’s 200 words on why you should add INNAX to your due-diligence list:

There was no question about what I wanted to invest in. The case for investing in real assets is compelling and well-established. I’m good at it and most investors are underexposed to these assets. So real asset management is all we do. We’re proud to say we’re an inch wide and a mile deep.

The only question was where I would be when I made those investments. I’ve spent the bulk of my career in very large asset management firms and I’d grown disillusioned with them. It was clear that large fund companies try to figure out what’s going to raise the most in terms of fees, and so what’s going to bring in the most fees. The strategies are often crafted by senior managers and marketing people who are concerned with getting something trendy up and out the door fast. You end up managing to a “product delivery specification” rather than managing for the best returns.

I launched Capital Innovations because I wanted the freedom and opportunity to serve clients and be truly innovative; we do that with global, all-cap portfolios that strive to avoid some of the pitfalls – overexposure to volatile commodity marketers, disastrous tax drags – that many natural resources funds fall prey to. We launched our fund at the request of some of our separate account clients who thought it would make a valuable strategy more broadly available.

Capital Innovations Global Agri, Timber, Infrastructure Fund has a $2500 minimum initial investment which is reduced to $500 for IRAs and other types of tax-advantaged accounts. Expenses are capped at 1.50% on the investor shares and 1.25% for institutional shares, with a 2.0% redemption fee on shares sold within 90 days. There’s a 5.75% front load that’s waived on some of the online platforms (e.g., Schwab). The fund has about gathered about $7 million in assets since its September 2012 launch. Here’s the fund’s homepage. It’s understandably thin on content yet but there’s some fairly rich analysis on the Capital Innovations page devoted to the underlying strategy. Our friends at DailyAlts.com interviewed Mr. Underhill in December 2014, and he laid out the case for real assets there. An exceptionally good overview of the case for real asset investing comes from Brookfield Asset Management, in Real Assets: The New Essential (2013) though everyone from TIAA-CREF to NACUBO have white papers on the subject.

My retirement portfolio has a small but permanent niche for real assets, which T. Rowe Price Real Assets (PRAFX) and Fidelity Strategic Real Return (FSRRX) filling that slot.

Launch Alert: Thornburg Better World

Earlier this summer, we argued that “doing good” and “doing well” were no longer incompatible goals, if they ever were. A host of academic and professional research has demonstrated that sustainable (or ESG) investing does not pose a drag on portfolio performance. That means that investors who would themselves never sell cigarettes or knowing pollute the environment can, with confidence, choose investing vehicles that honor those principles.

The roster of options expanded by one on October 1, with the launch of Thornburg Better World International Fund (TBWAX). The fund will target “high-quality, attractively priced companies making a positive impact on the world.” That differs from traditional socially-responsible investments which focused mostly on negative screens; that is, they worked to exclude evil-doers rather than seeking out firms that will have a positive impact.

They’ll examine a number of characteristics in assessing a firm’s sustainability: “environmental impact, carbon footprint, senior management diversity, regulatory and compliance track record, board independence, capital allocation decisions, relationships with communities and customers, product safety, labor and employee development practices, relationships with vendors, workplace safety, and regulatory compliance, among others.”

The fund is managed by Rolf Kelly, CFA, portfolio manager of Thornburg’s Socially Screened International Equity Strategy (SMA). The portfolio will have 30-60 names. The initial expense ratio is 1.83%. The minimum initial investment is $5000.

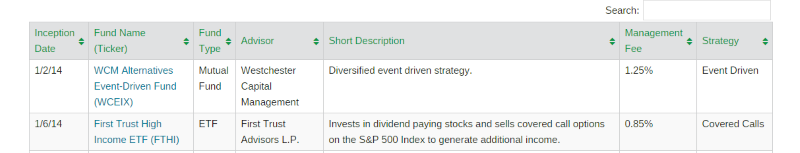

Funds in Registration

There are seven new funds in registration this month. Funds in registration with the SEC are not available for sale to the public and the advisors are not permitted to talk about them, but a careful reading of the filed prospectuses gives you a good idea of what interesting (and occasionally appalling) options are in the pipeline. Funds currently in registration will generally be available for purchase in December.